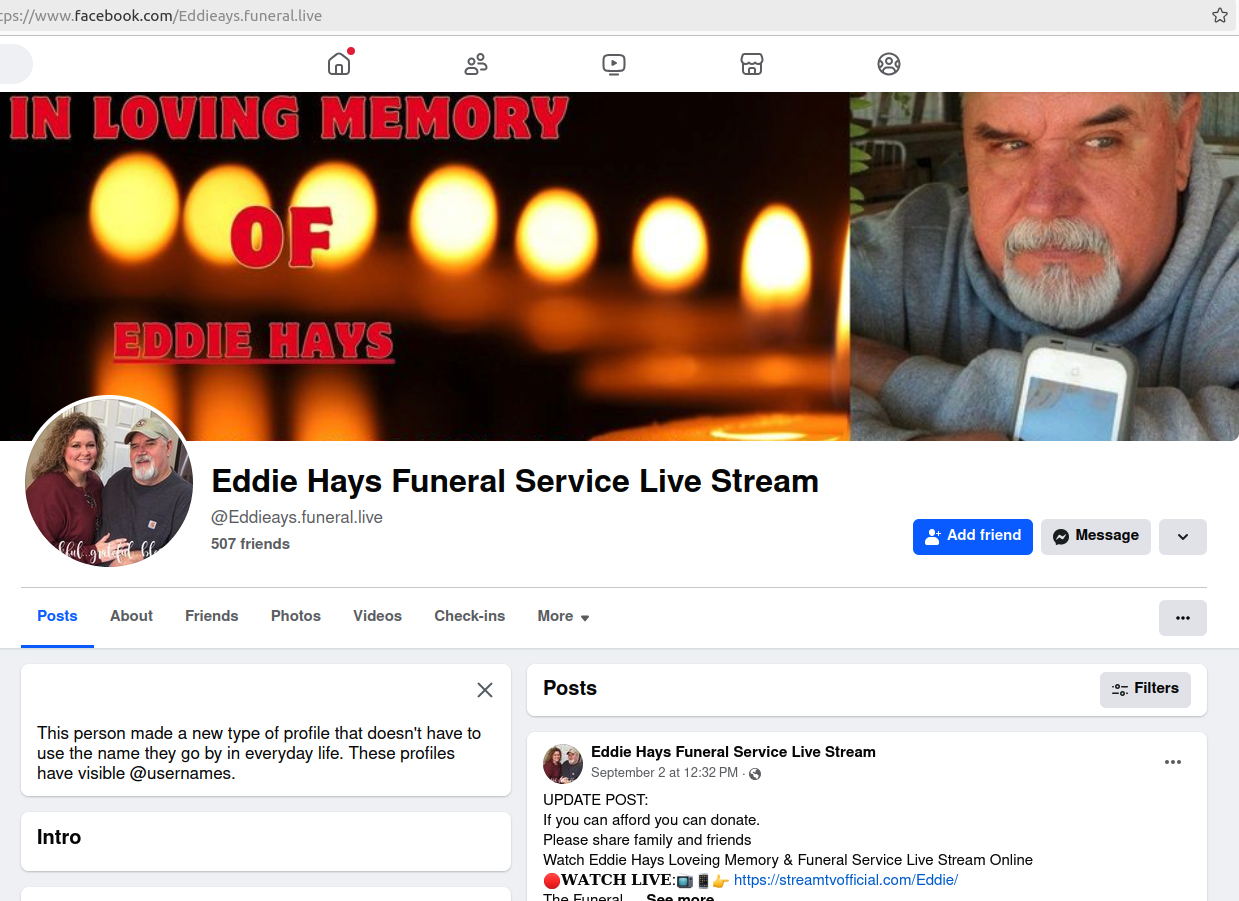

A 26-year-old man in Ontario, Canada has been arrested for allegedly stealing data from and extorting more than 160 companies that used the cloud data service Snowflake.

On October 30, Canadian authorities arrested Alexander Moucka, a.k.a. Connor Riley Moucka of Kitchener, Ontario, on a provisional arrest warrant from the United States. Bloomberg first reported Moucka’s alleged ties to the Snowflake hacks on Monday.

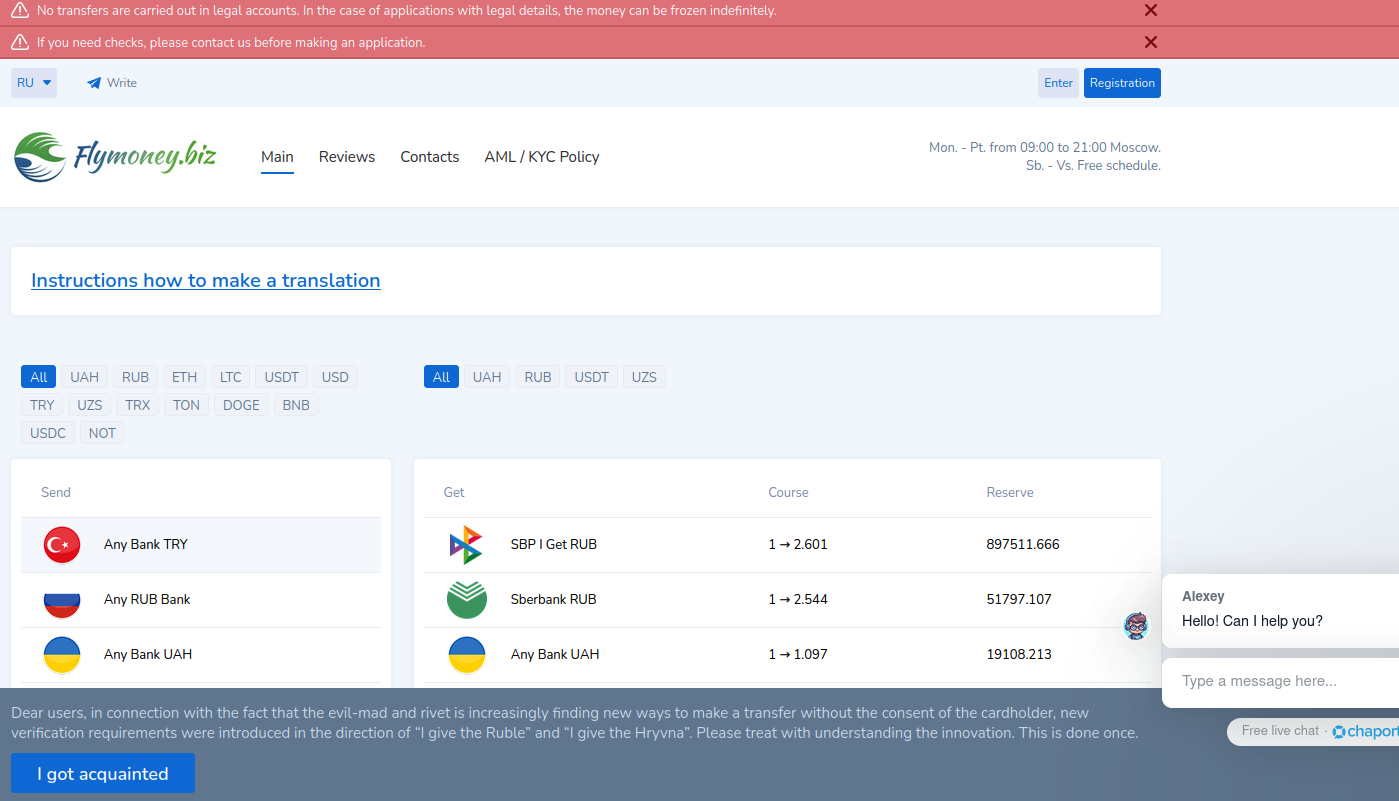

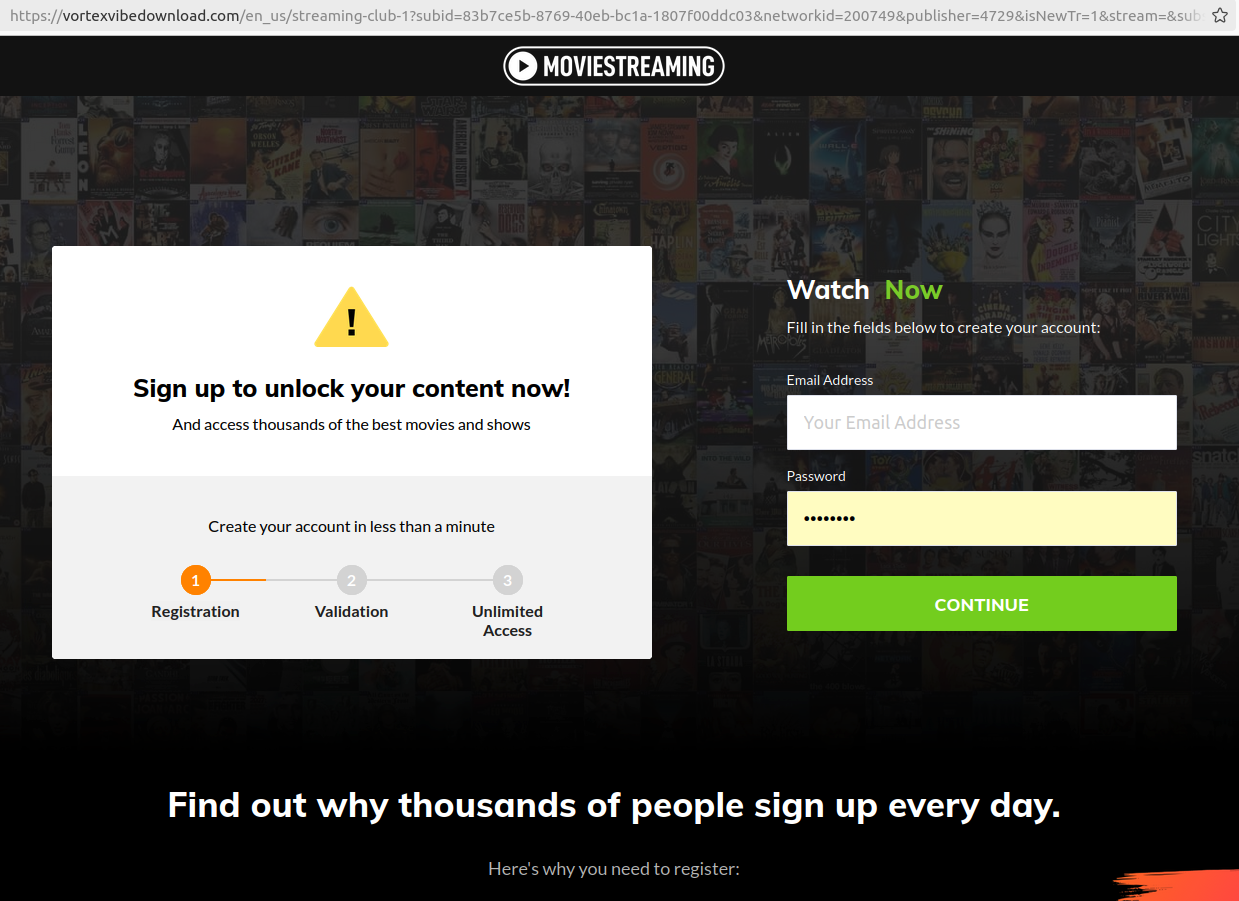

At the end of 2023, malicious hackers learned that many large companies had uploaded huge volumes of sensitive customer data to Snowflake accounts that were protected with little more than a username and password (no multi-factor authentication required). After scouring darknet markets for stolen Snowflake account credentials, the hackers began raiding the data storage repositories used by some of the world’s largest corporations.

Among those was AT&T, which disclosed in July that cybercriminals had stolen personal information and phone and text message records for roughly 110 million people — nearly all of its customers. Wired.com reported in July that AT&T paid a hacker $370,000 to delete stolen phone records.

A report on the extortion attacks from the incident response firm Mandiant notes that Snowflake victim companies were privately approached by the hackers, who demanded a ransom in exchange for a promise not to sell or leak the stolen data. All told, more than 160 Snowflake customers were relieved of data, including TicketMaster, Lending Tree, Advance Auto Parts and Neiman Marcus.

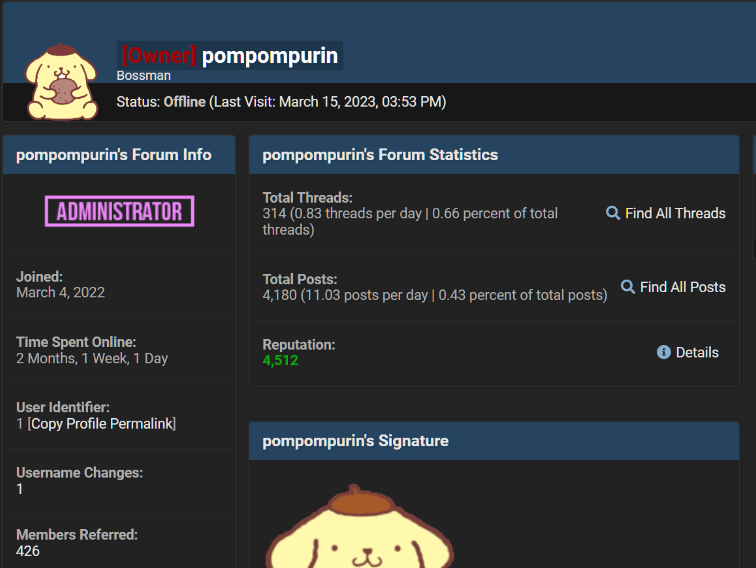

Moucka is alleged to have used the hacker handles Judische and Waifu, among many others. These monikers correspond to a prolific cybercriminal whose exploits were the subject of a recent story published here about the overlap between Western, English-speaking cybercriminals and extremist groups that harass and extort minors into harming themselves or others.

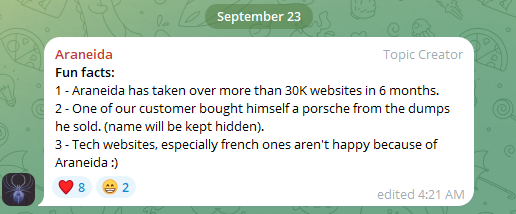

On May 2, 2024, Judische claimed on the fraud-focused Telegram channel Star Chat that they had hacked Santander Bank, one of the first known Snowflake victims. Judische would repeat that claim in Star Chat on May 13 — the day before Santander publicly disclosed a data breach — and would periodically blurt out the names of other Snowflake victims before their data even went up for sale on the cybercrime forums.

404 Media reports that at a court hearing in Ontario this morning, Moucka called in from a prison phone and said he was seeking legal aid to hire an attorney.

KrebsOnSecurity has learned that Moucka is currently named in multiple indictments issued by U.S. prosecutors and federal law enforcement agencies. However, it is unclear which specific charges the indictments contain, as all of those cases remain under seal.

TELECOM DOMINOES

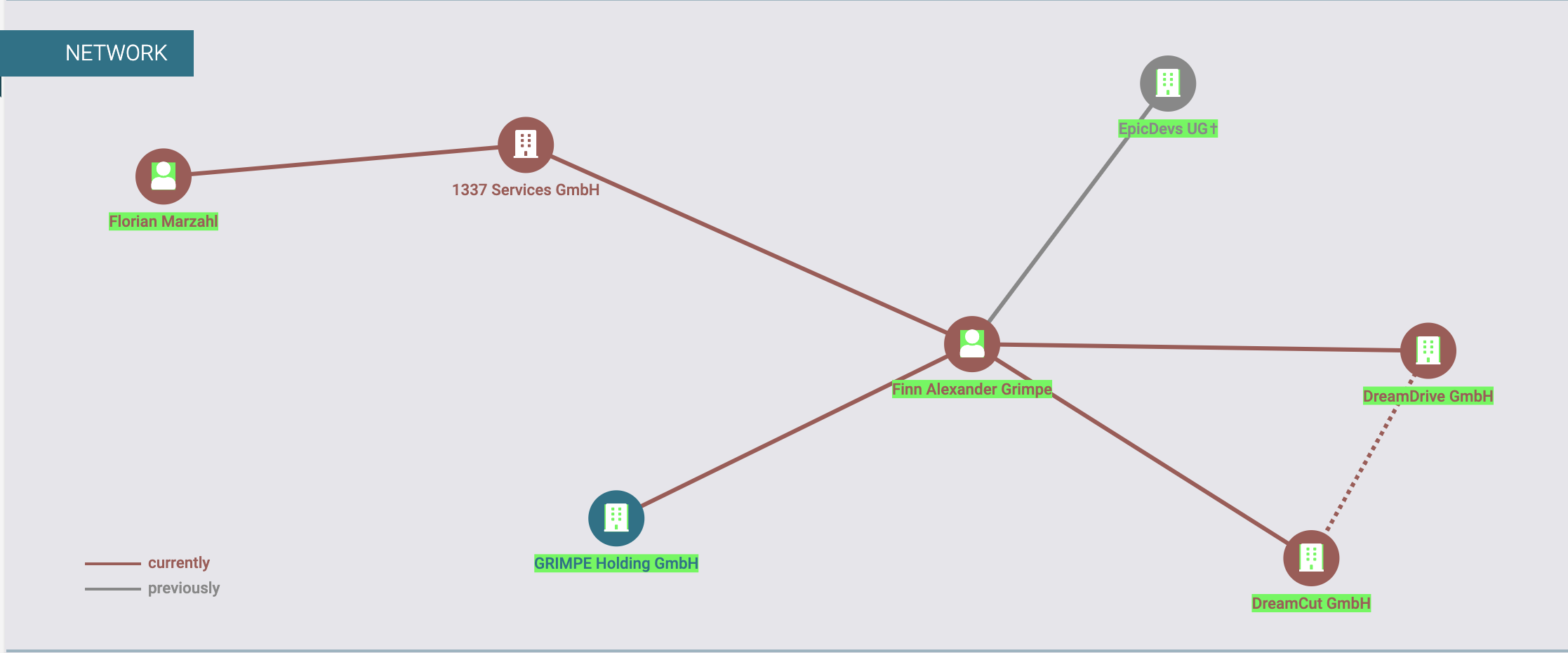

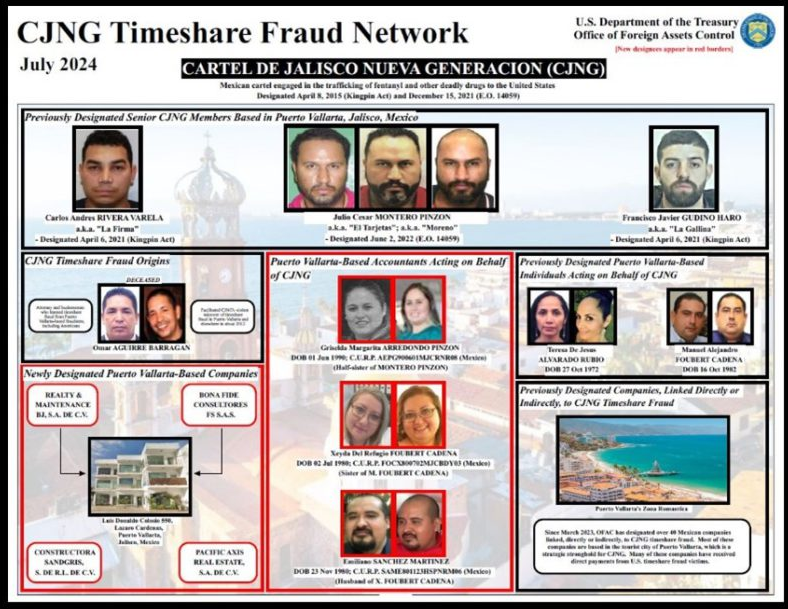

Mandiant has attributed the Snowflake compromises to a group it calls “UNC5537,” with members based in North America and Turkey. Sources close to the investigation tell KrebsOnSecurity the UNC5537 member in Turkey is John Erin Binns, an elusive American man indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) for a 2021 breach at T-Mobile that exposed the personal information of at least 76.6 million customers.

Sources involved in the investigation said UNC5537 has focused on hacking into telecommunications companies around the world. Those sources told KrebsOnSecurity that Binns and Judische are suspected of stealing data from India’s largest state-run telecommunications firm Bharat Sanchar Nigam Ltd (BNSL), and that the duo even bragged about being able to intercept or divert phone calls and text messages for a large portion of the population of India.

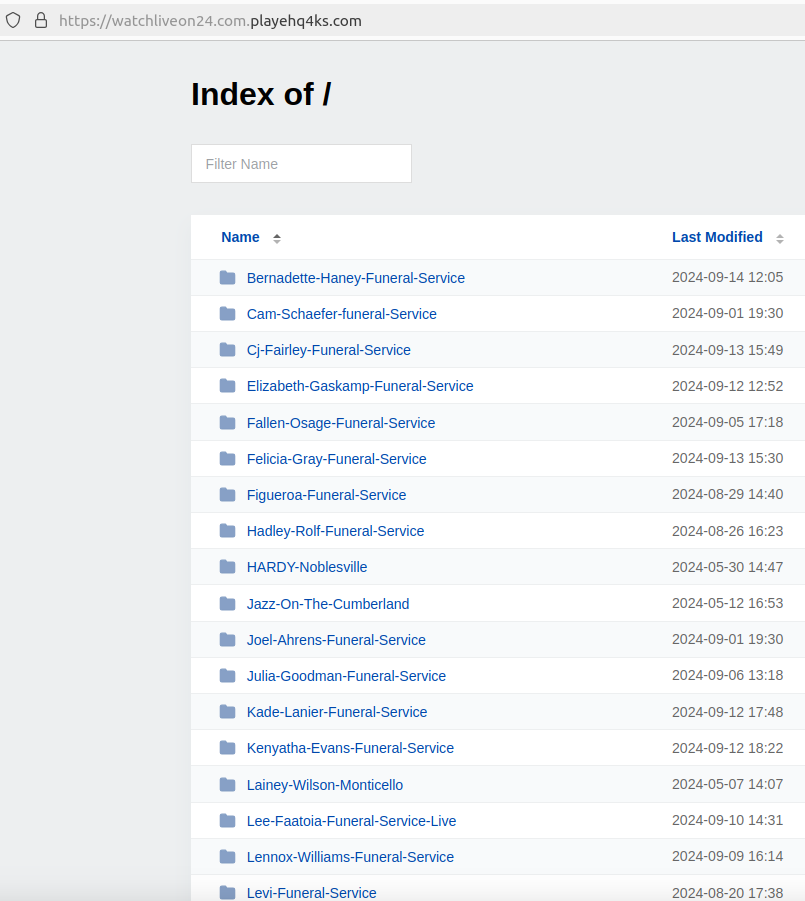

Judische appears to have outsourced the sale of databases from victim companies who refuse to pay, delegating some of that work to a cybercriminal who uses the nickname Kiberphant0m on multiple forums. In late May 2024, Kiberphant0m began advertising the sale of hundreds of gigabytes of data stolen from BSNL.

“Information is worth several million dollars but I’m selling for pretty cheap,” Kiberphant0m wrote of the BSNL data in a post on the English-language cybercrime community Breach Forums. “Negotiate a deal in Telegram.”

Also in May 2024, Kiberphant0m took to the Russian-language hacking forum XSS to sell more than 250 gigabytes of data stolen from an unnamed mobile telecom provider in Asia, including a database of all active customers and software allowing the sending of text messages to all customers.

On September 3, 2024, Kiberphant0m posted a sales thread on XSS titled “Selling American Telecom Access (100B+ Revenue).” Kiberphant0m’s asking price of $200,000 was apparently too high because they reposted the sales thread on Breach Forums a month later, with a headline that more clearly explained the data was stolen from Verizon‘s “push-to-talk” (PTT) customers — primarily U.S. government agencies and first responders.

404Media reported recently that the breach does not appear to impact the main consumer Verizon network. Rather, the hackers broke into a third party provider and stole data on Verizon’s PTT systems, which are a separate product marketed towards public sector agencies, enterprises, and small businesses to communicate internally.

INTERVIEW WITH JUDISCHE

Investigators say Moucka shared a home in Kitchener with other tenants, but not his family. His mother was born in Chechnya, and he speaks Russian in addition to French and English. Moucka’s father died of a drug overdose at age 26, when the defendant was roughly five years old.

A person claiming to be Judische began communicating with this author more than three months ago on Signal after KrebsOnSecurity started asking around about hacker nicknames previously used by Judische over the years (Waifu, Ned, Nedral Onfroy, Noctuliuss, and November).

Judische admitted to stealing and ransoming data from Snowflake customers, but he said he’s not interested in selling the information, and that others have done this with some of the data sets he stole.

“I’m not really someone that sells data unless it’s crypto [databases] or credit cards because they’re the only thing I can find buyers for that actually have money for the data,” Judische told KrebsOnSecurity. “The rest is just ransom.”

Judische has sent this reporter dozens of unsolicited and often profane messages from several different Signal accounts, all of which claimed to be an anonymous tipster sharing different identifying details for Judische. This appears to have been an elaborate effort by Judische to “detrace” his movements online and muddy the waters about his identity.

Judische frequently claimed he had unparalleled “opsec” or operational security, a term that refers to the ability to compartmentalize and obfuscate one’s tracks online. On several occasions, he shared screenshots and other information indicating someone with access to intelligence gathered by Mandiant had given him the company’s assessment of who and where they thought he was.

But in a conversation with KrebsOnSecurity on October 26, Judische acknowledged it was likely that the authorities were closing in on him, and said he would seriously answer certain questions about his personal life.

“They’re coming after me for sure,” he said.

In several previous conversations, Judische referenced suffering from an unspecified personality disorder, and when pressed said he has a condition called “schizotypal personality disorder” (STPD).

According to the Cleveland Clinic, schizotypal personality disorder is marked by a consistent pattern of intense discomfort with relationships and social interactions: “People with STPD have unusual thoughts, speech and behaviors, which usually hinder their ability to form and maintain relationships.”

Judische said he was prescribed medication for his psychological issues, but that he doesn’t take his meds. Which might explain why he never leaves his home.

“I never go outside,” Judische allowed. “I’ve never had a friend or true relationship not online nor in person. I see people as vehicles to achieve my ends no matter how friendly I may seem on the surface, which you can see by how fast I discard people who are loyal or [that] I’ve known a long time.”

Judische later admitted he doesn’t have an official STPD diagnosis from a physician, but said he knows that he exhibits all the signs of someone with this condition.

“I can’t actually get diagnosed with that either,” Judische shared. “Most countries put you on lists and restrict you from certain things if you have it.”

Asked whether he has always lived at his current residence, Judische replied that he had to leave his hometown for his own safety.

“I can’t live safely where I’m from without getting robbed or arrested,” he said, without offering more details.

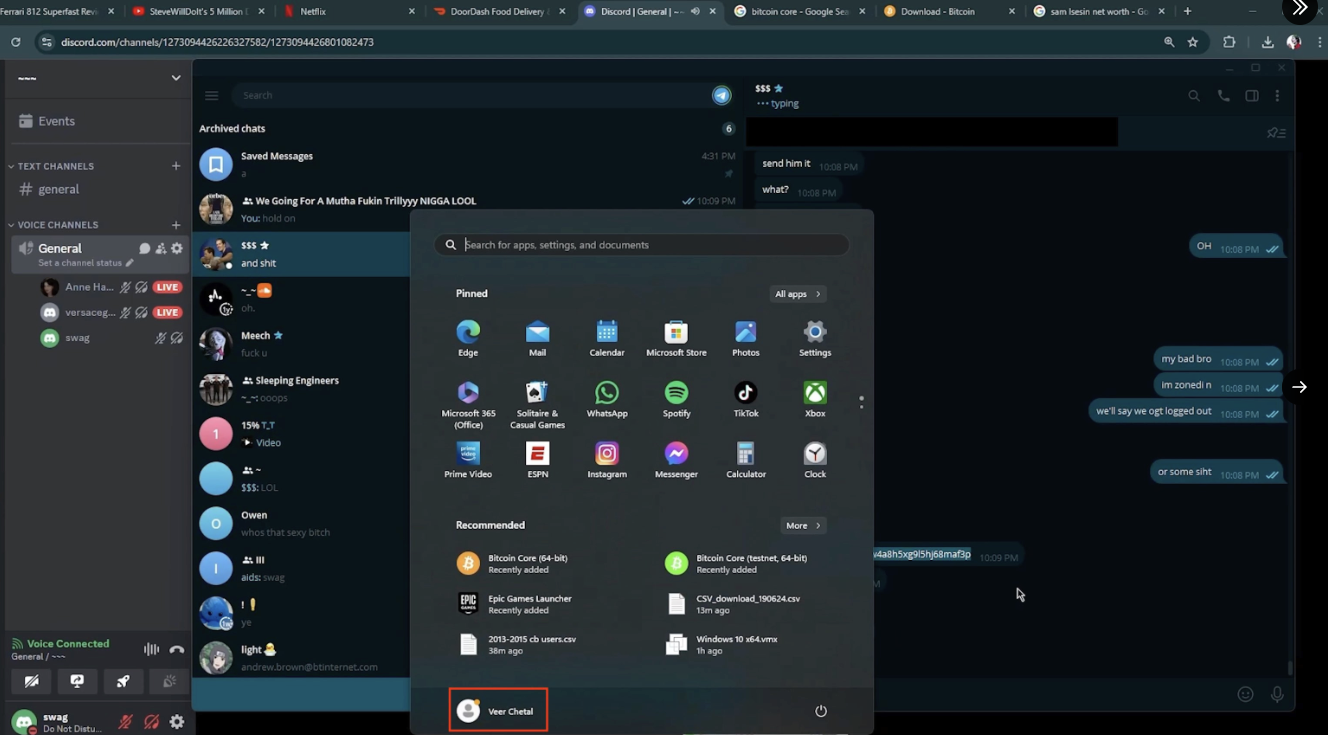

A source familiar with the investigation said Moucka previously lived in Quebec, which he allegedly fled after being charged with harassing others on the social network Discord.

Judische claims to have made at least $4 million in his Snowflake extortions, but investigators told KrebsOnSecurity the true figure is likely in the double digits and possibly more than $20 million (although it’s unclear how much of that had to be shared with co-conspirators).

Judische said he and others frequently targeted business process outsourcing (BPO) companies, staffing firms that handle customer service for a wide range of organizations. They also went after managed service providers (MSPs) that oversee IT support and security for multiple companies, he claimed.

“Snowflake isn’t even the biggest BPO/MSP multi-company dataset on our networks, but what’s been exfiltrated from them is well over 100TB,” Judische bragged. “Only ones that don’t pay get disclosed (unless they disclose it themselves). A lot of them don’t even do their SEC filing and just pay us to fuck off.”

INTEL SECRETS

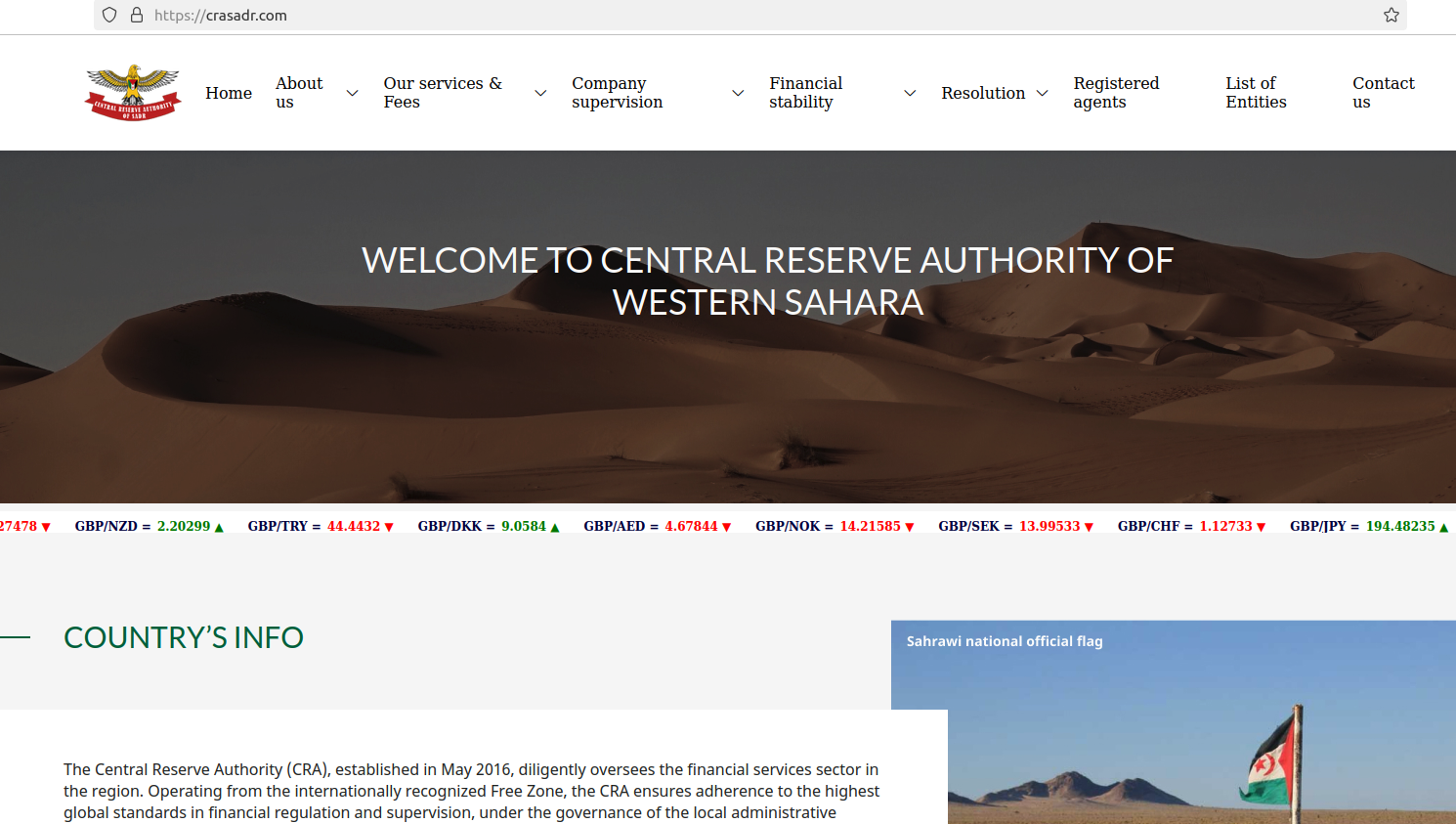

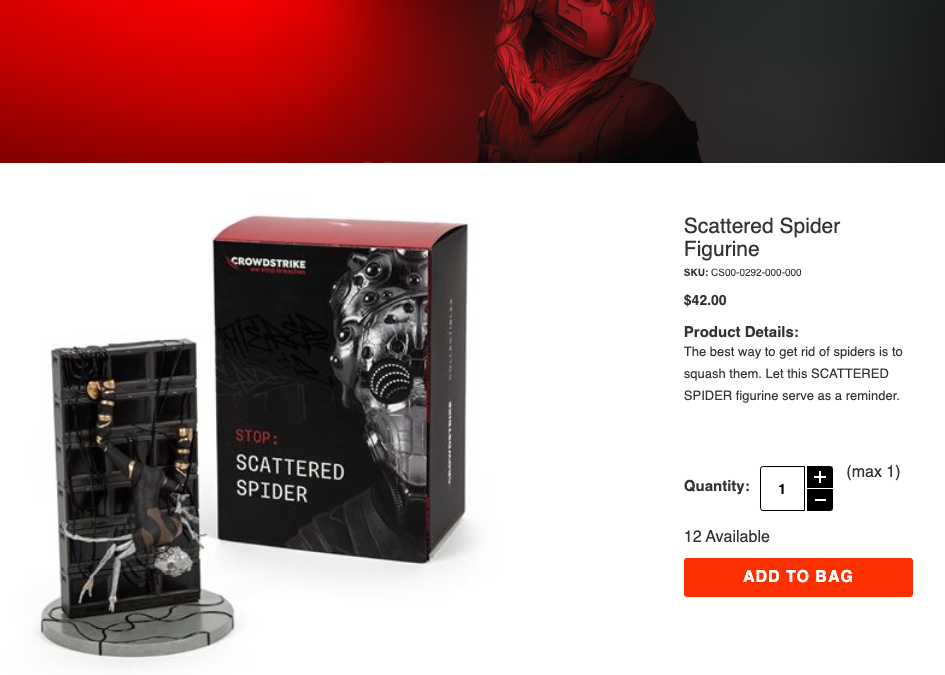

The other half of UNC5537 — 24-year-old John Erin Binns — was arrested in Turkey in late May 2024, and currently resides in a Turkish prison. However, it is unclear if Binns faces any immediate threat of extradition to the United States, where he is currently wanted on criminal hacking charges tied to the 2021 breach at T-Mobile.

A person familiar with the investigation said Binns’s application for Turkish citizenship was inexplicably approved after his incarceration, leading to speculation that Binns may have bought his way out of a sticky legal situation.

Under the Turkish constitution, a Turkish citizen cannot be extradited to a foreign state. Turkey has been criticized for its “golden passport” program, which provides citizenship and sanctuary for anyone willing to pay several hundred thousand dollars.

This is an image of a passport that Binns shared in one of many unsolicited emails to KrebsOnSecurity since 2021. Binns never explained why he sent this in Feb. 2023.

Binns’s alleged hacker alter egos — “IRDev” and “IntelSecrets” — were at once feared and revered on several cybercrime-focused Telegram communities, because he was known to possess a powerful weapon: A massive botnet. From reviewing the Telegram channels Binns frequented, we can see that others in those communities — including Judische — heavily relied on Binns and his botnet for a variety of cybercriminal purposes.

The IntelSecrets nickname corresponds to an individual who has claimed responsibility for modifying the source code for the Mirai “Internet of Things” botnet to create a variant known as “Satori,” and supplying it to others who used it for criminal gain and were later caught and prosecuted.

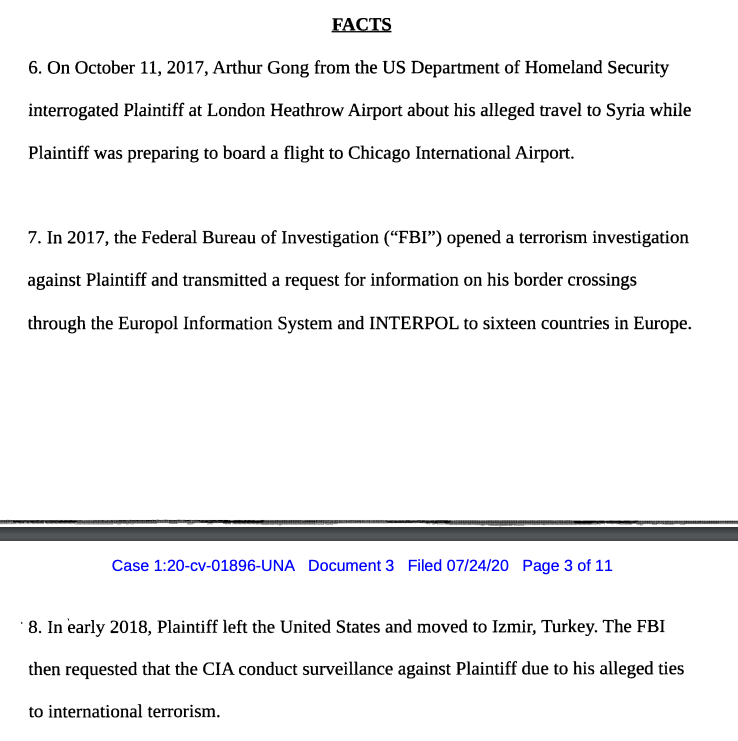

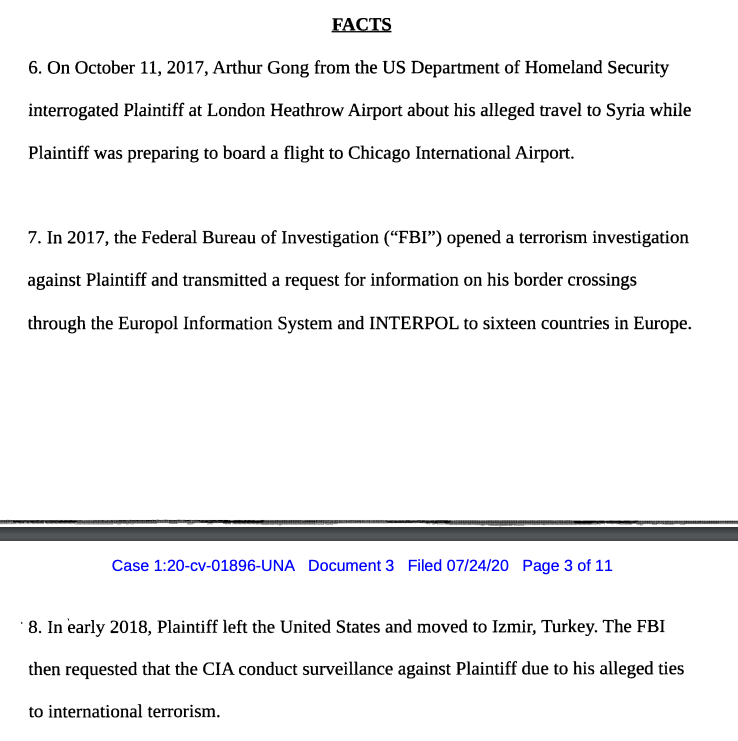

Since 2020, Binns has filed a flood of lawsuits naming various federal law enforcement officers and agencies — including the FBI, the CIA, and the U.S. Special Operations Command (PDF), demanding that the government turn over information collected about him and seeking restitution for his alleged kidnapping at the hands of the CIA.

Binns claims he was kidnapped in Turkey and subjected to various forms of psychological and physical torture. According to Binns, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) falsely told their counterparts in Turkey that he was a supporter or member of the Islamic State (ISIS), a claim he says led to his detention and torture by the Turkish authorities.

However, in a 2020 lawsuit he filed against the CIA, Binns himself acknowledged having visited a previously ISIS-controlled area of Syria prior to moving to Turkey in 2017.

A segment of a lawsuit Binns filed in 2020 against the CIA, in which he alleges U.S. put him on a terror watch list after he traveled to Syria in 2017.

Sources familiar with the investigation told KrebsOnSecurity that Binns was so paranoid about possible surveillance on him by American and Turkish intelligence agencies that his erratic behavior and online communications actually brought about the very government snooping that he feared.

In several online chats in late 2023 on Discord, IRDev lamented being lured into a law enforcement sting operation after trying to buy a rocket launcher online. A person close to the investigation confirmed that at the beginning of 2023, IRDev began making earnest inquiries about how to purchase a Stinger, an American-made portable weapon that operates as an infrared surface-to-air missile.

Sources told KrebsOnSecurity Binns’ repeated efforts to purchase the projectile earned him multiple visits from the Turkish authorities, who were justifiably curious why he kept seeking to acquire such a powerful weapon.

WAIFU

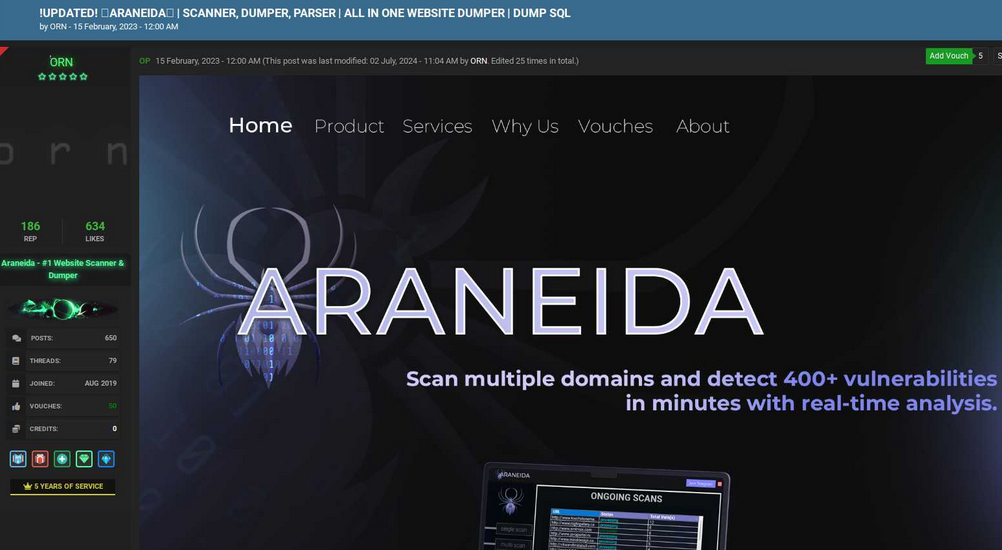

A careful study of Judische’s postings on Telegram and Discord since 2019 shows this user is more widely known under the nickname “Waifu,” a moniker that corresponds to one of the more accomplished “SIM swappers” in the English-language cybercrime community over the years.

SIM swapping involves phishing, tricking or bribing mobile phone company employees for credentials needed to redirect a target’s mobile phone number to a device the attackers control — allowing thieves to intercept incoming text messages and phone calls.

Several SIM-swapping channels on Telegram maintain a frequently updated leaderboard of the 100 richest SIM-swappers, as well as the hacker handles associated with specific cybercrime groups (Waifu is ranked #24). That list has long included Waifu on a roster of hackers for a group that called itself “Beige.”

The term “Beige Group” came up in reporting on two stories published here in 2020. The first was in an August 2020 piece called Voice Phishers Targeting Corporate VPNs, which warned that the COVID-19 epidemic had brought a wave of targeted voice phishing attacks that tried to trick work-at-home employees into providing access to their employers’ networks. Frequent targets of the Beige group included employees at numerous top U.S. banks, ISPs, and mobile phone providers.

The second time Beige Group was mentioned by sources was in reporting on a breach at the domain registrar GoDaddy. In November 2020, intruders thought to be associated with the Beige Group tricked a GoDaddy employee into installing malicious software, and with that access they were able to redirect the web and email traffic for multiple cryptocurrency trading platforms. Other frequent targets of the Beige group included employees at numerous top U.S. banks, ISPs, and mobile phone providers.

Judische’s various Telegram identities have long claimed involvement in the 2020 GoDaddy breach, and he didn’t deny his alleged role when asked directly. Judische said he prefers voice phishing or “vishing” attacks that result in the target installing data-stealing malware, as opposed to tricking the user into entering their username, password and one-time code.

“Most of my ops involve malware [because] credential access burns too fast,” Judische explained.

CRACKDOWN ON HARM GROUPS?

The Telegram channels that the Judische/Waifu accounts frequented over the years show this user divided their time between posting in channels dedicated to financial cybercrime, and harassing and stalking others in harm communities like Leak Society and Court.

Both of these Telegram communities are known for victimizing children through coordinated online campaigns of extortion, doxing, swatting and harassment. People affiliated with harm groups like Court and Leak Society will often recruit new members by lurking on gaming platforms, social media sites and mobile applications that are popular with young people, including Discord, Minecraft, Roblox, Steam, Telegram, and Twitch.

“This type of offence usually starts with a direct message through gaming platforms and can move to more private chatrooms on other virtual platforms, typically one with video enabled features, where the conversation quickly becomes sexualized or violent,” warns a recent alert from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) about the rise of sextortion groups on social media channels.

“One of the tactics being used by these actors is sextortion, however, they are not using it to extract money or for sexual gratification,” the RCMP continued. “Instead they use it to further manipulate and control victims to produce more harmful and violent content as part of their ideological objectives and radicalization pathway.”

Some of the largest such known groups include those that go by the names 764, CVLT, Kaskar, 7997, 8884, 2992, 6996, 555, Slit Town, 545, 404, NMK, 303, and H3ll.

On the various cybercrime-oriented channels Judische frequented, he often lied about his or others’ involvement in various breaches. But Judische also at times shared nuggets of truth about his past, particularly when discussing the early history and membership of specific Telegram- and Discord-based cybercrime and harm groups.

Judische claimed in multiple chats, including on Leak Society and Court, that they were an early member of the Atomwaffen Division (AWD), a white supremacy group whose members are suspected of having committed multiple murders in the U.S. since 2017.

In 2019, KrebsOnSecurity exposed how a loose-knit group of neo-Nazis, some of whom were affiliated with AWD, had doxed and/or swatted nearly three dozen journalists at a range of media publications. Swatting involves communicating a false police report of a bomb threat or hostage situation and tricking authorities into sending a heavily armed police response to a targeted address.

Judsiche also told a fellow denizen of Court that years ago he was active in an older harm community called “RapeLash,” a truly vile Discord server known for attracting Atomwaffen members. A 2018 retrospective on RapeLash posted to the now defunct neo-Nazi forum Fascist Forge explains that RapeLash was awash in gory, violent images and child pornography.

A Fascist Forge member named “Huddy” recalled that RapeLash was the third incarnation of an extremist community also known as “FashWave,” short for Fascist Wave.

“I have no real knowledge of what happened with the intermediary phase known as ‘FashWave 2.0,’ but FashWave 3.0 houses multiple known Satanists and other degenerates connected with AWD, one of which got arrested on possession of child pornography charges, last I heard,” Huddy shared.

In June 2024, a Mandiant employee told Bloomberg that UNC5537 members have made death threats against cybersecurity experts investigating the hackers, and that in one case the group used artificial intelligence to create fake nude photos of a researcher to harass them.

Allison Nixon is chief research officer with the New York-based cybersecurity firm Unit 221B. Nixon is among several researchers who have faced harassment and specific threats of physical violence from Judische.

Nixon said Judische is likely to argue in court that his self-described psychological disorder(s) should somehow excuse his long career in cybercrime and in harming others.

“They ran a misinformation campaign in a sloppy attempt to cover up the hacking campaign,” Nixon said of Judische. “Coverups are an acknowledgment of guilt, which will undermine a mental illness defense in court. We expect that violent hackers from the [cybercrime community] will experience increasingly harsh sentences as the crackdown continues.”