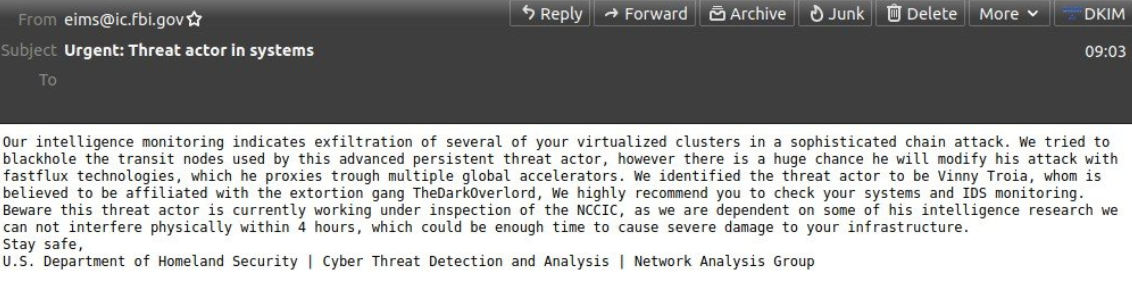

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is urging police departments and governments worldwide to beef up security around their email systems, citing a recent increase in cybercriminal services that use hacked police email accounts to send unauthorized subpoenas and customer data requests to U.S.-based technology companies.

In an alert (PDF) published this week, the FBI said it has seen un uptick in postings on criminal forums regarding the process of emergency data requests (EDRs) and the sale of email credentials stolen from police departments and government agencies.

“Cybercriminals are likely gaining access to compromised US and foreign government email addresses and using them to conduct fraudulent emergency data requests to US based companies, exposing the personal information of customers to further use for criminal purposes,” the FBI warned.

In the United States, when federal, state or local law enforcement agencies wish to obtain information about an account at a technology provider — such as the account’s email address, or what Internet addresses a specific cell phone account has used in the past — they must submit an official court-ordered warrant or subpoena.

Virtually all major technology companies serving large numbers of users online have departments that routinely review and process such requests, which are typically granted (eventually, and at least in part) as long as the proper documents are provided and the request appears to come from an email address connected to an actual police department domain name.

In some cases, a cybercriminal will offer to forge a court-approved subpoena and send that through a hacked police or government email account. But increasingly, thieves are relying on fake EDRs, which allow investigators to attest that people will be bodily harmed or killed unless a request for account data is granted expeditiously.

The trouble is, these EDRs largely bypass any official review and do not require the requester to supply any court-approved documents. Also, it is difficult for a company that receives one of these EDRs to immediately determine whether it is legitimate.

In this scenario, the receiving company finds itself caught between two unsavory outcomes: Failing to immediately comply with an EDR — and potentially having someone’s blood on their hands — or possibly leaking a customer record to the wrong person.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, compliance with such requests tends to be extremely high. For example, in its most recent transparency report (PDF) Verizon said it received more than 127,000 law enforcement demands for customer data in the second half of 2023 — including more than 36,000 EDRs — and that the company provided records in response to approximately 90 percent of requests.

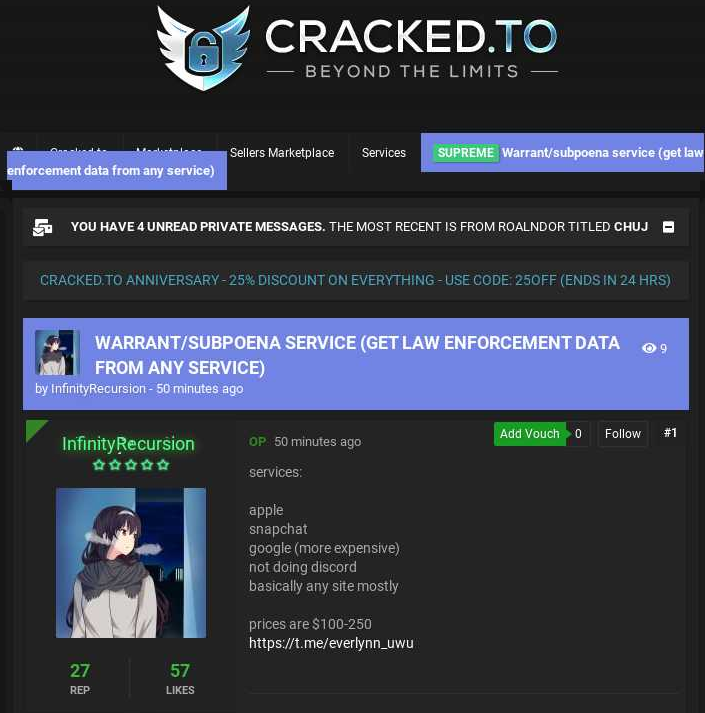

One English-speaking cybercriminal who goes by the nicknames “Pwnstar” and “Pwnipotent” has been selling fake EDR services on both Russian-language and English cybercrime forums. Their prices range from $1,000 to $3,000 per successful request, and they claim to control “gov emails from over 25 countries,” including Argentina, Bangladesh, Brazil, Bolivia, Dominican Republic, Hungary, India, Kenya, Jordan, Lebanon, Laos, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Vietnam.

“I cannot 100% guarantee every order will go through,” Pwnstar explained. “This is social engineering at the highest level and there will be failed attempts at times. Don’t be discouraged. You can use escrow and I give full refund back if EDR doesn’t go through and you don’t receive your information.”

An ad from Pwnstar for fake EDR services.

A review of EDR vendors across many cybercrime forums shows that some fake EDR vendors sell the ability to send phony police requests to specific social media platforms, including forged court-approved documents. Others simply sell access to hacked government or police email accounts, and leave it up to the buyer to forge any needed documents.

“When you get account, it’s yours, your account, your liability,” reads an ad in October on BreachForums. “Unlimited Emergency Data Requests. Once Paid, the Logins are completely Yours. Reset as you please. You would need to Forge Documents to Successfully Emergency Data Request.”

Still other fake EDR service vendors claim to sell hacked or fraudulently created accounts on Kodex, a startup that aims to help tech companies do a better job screening out phony law enforcement data requests. Kodex is trying to tackle the problem of fake EDRs by working directly with the data providers to pool information about police or government officials submitting these requests, with an eye toward making it easier for everyone to spot an unauthorized EDR.

If police or government officials wish to request records regarding Coinbase customers, for example, they must first register an account on Kodexglobal.com. Kodex’s systems then assign that requestor a score or credit rating, wherein officials who have a long history of sending valid legal requests will have a higher rating than someone sending an EDR for the first time.

It is not uncommon to see fake EDR vendors claim the ability to send data requests through Kodex, with some even sharing redacted screenshots of police accounts at Kodex.

Matt Donahue is the former FBI agent who founded Kodex in 2021. Donahue said just because someone can use a legitimate police department or government email to create a Kodex account doesn’t mean that user will be able to send anything. Donahue said even if one customer gets a fake request, Kodex is able to prevent the same thing from happening to another.

Kodex told KrebsOnSecurity that over the past 12 months it has processed a total of 1,597 EDRs, and that 485 of those requests (~30 percent) failed a second-level verification. Kodex reports it has suspended nearly 4,000 law enforcement users in the past year, including:

-1,521 from the Asia-Pacific region;

-1,290 requests from Europe, the Middle East and Asia;

-460 from police departments and agencies in the United States;

-385 from entities in Latin America, and;

-285 from Brazil.

Donahue said 60 technology companies are now routing all law enforcement data requests through Kodex, including an increasing number of financial institutions and cryptocurrency platforms. He said one concern shared by recent prospective customers is that crooks are seeking to use phony law enforcement requests to freeze and in some cases seize funds in specific accounts.

“What’s being conflated [with EDRs] is anything that doesn’t involve a formal judge’s signature or legal process,” Donahue said. “That can include control over data, like an account freeze or preservation request.”

In a hypothetical example, a scammer uses a hacked government email account to request that a service provider place a hold on a specific bank or crypto account that is allegedly subject to a garnishment order, or party to crime that is globally sanctioned, such as terrorist financing or child exploitation.

A few days or weeks later, the same impersonator returns with a request to seize funds in the account, or to divert the funds to a custodial wallet supposedly controlled by government investigators.

“In terms of overall social engineering attacks, the more you have a relationship with someone the more they’re going to trust you,” Donahue said. “If you send them a freeze order, that’s a way to establish trust, because [the first time] they’re not asking for information. They’re just saying, ‘Hey can you do me a favor?’ And that makes the [recipient] feel valued.”

Echoing the FBI’s warning, Donahue said far too many police departments in the United States and other countries have poor account security hygiene, and often do not enforce basic account security precautions — such as requiring phishing-resistant multifactor authentication.

How are cybercriminals typically gaining access to police and government email accounts? Donahue said it’s still mostly email-based phishing, and credentials that are stolen by opportunistic malware infections and sold on the dark web. But as bad as things are internationally, he said, many law enforcement entities in the United States still have much room for improvement in account security.

“Unfortunately, a lot of this is phishing or malware campaigns,” Donahue said. “A lot of global police agencies don’t have stringent cybersecurity hygiene, but even U.S. dot-gov emails get hacked. Over the last nine months, I’ve reached out to CISA (the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency) over a dozen times about .gov email addresses that were compromised and that CISA was unaware of.”

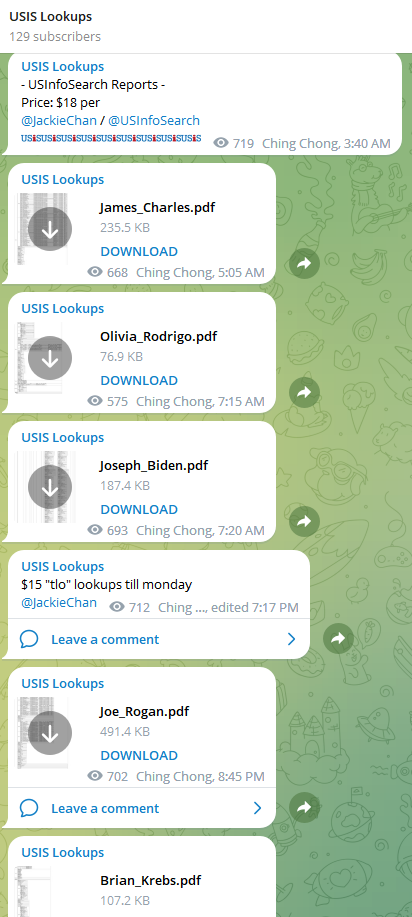

Since at least February 2023, a service advertised on Telegram called USiSLookups has operated an automated bot that allows anyone to look up the SSN or background report on virtually any American. For prices ranging from $8 to $40 and payable via virtual currency, the bot will return detailed consumer background reports automatically in just a few moments.

Since at least February 2023, a service advertised on Telegram called USiSLookups has operated an automated bot that allows anyone to look up the SSN or background report on virtually any American. For prices ranging from $8 to $40 and payable via virtual currency, the bot will return detailed consumer background reports automatically in just a few moments.