Thread hijacking attacks. They happen when someone you know has their email account compromised, and you are suddenly dropped into an existing conversation between the sender and someone else. These missives draw on the recipient’s natural curiosity about being copied on a private discussion, which is modified to include a malicious link or attachment. Here’s the story of a recent thread hijacking attack in which a journalist was copied on a phishing email from the unwilling subject of a recent scoop.

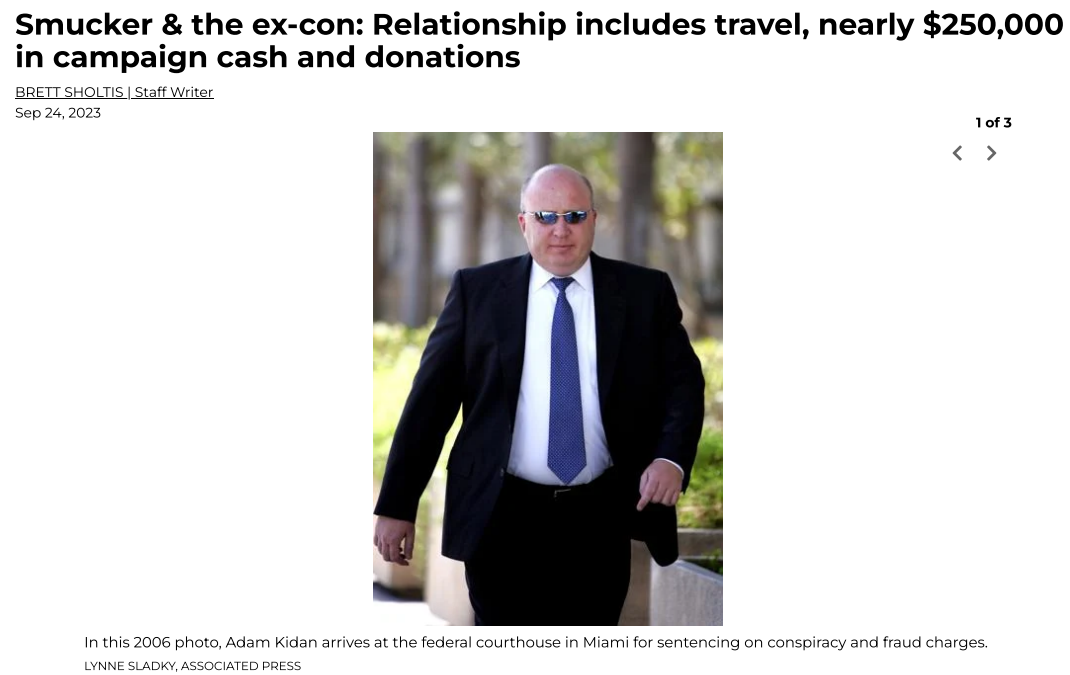

In Sept. 2023, the Pennsylvania news outlet LancasterOnline.com published a story about Adam Kidan, a wealthy businessman with a criminal past who is a major donor to Republican causes and candidates, including Rep. Lloyd Smucker (R-Pa).

The LancasterOnline story about Adam Kidan.

Several months after that piece ran, the story’s author Brett Sholtis received two emails from Kidan, both of which contained attachments. One of the messages appeared to be a lengthy conversation between Kidan and a colleague, with the subject line, “Re: Successfully sent data.” The second missive was a more brief email from Kidan with the subject, “Acknowledge New Work Order,” and a message that read simply, “Please find the attached.”

Sholtis said he clicked the attachment in one of the messages, which then launched a web page that looked exactly like a Microsoft Office 365 login page. An analysis of the webpage reveals it would check any submitted credentials at the real Microsoft website, and return an error if the user entered bogus account information. A successful login would record the submitted credentials and forward the victim to the real Microsoft website.

But Sholtis said he didn’t enter his Outlook username and password. Instead, he forwarded the messages to LancasterOneline’s IT team, which quickly flagged them as phishing attempts.

LancasterOnline’s Executive Editor Tom Murse said the two phishing messages from Mr. Kidan raised eyebrows in the newsroom because Kidan had threatened to sue the news outlet multiple times over Sholtis’s story.

“We were just perplexed,” Murse said. “It seemed to be a phishing attempt but we were confused why it would come from a prominent businessman we’ve written about. Our initial response was confusion, but we didn’t know what else to do with it other than to send it to the FBI.”

The phishing lure attached to the thread hijacking email from Mr. Kidan.

In 2006, Kidan was sentenced to 70 months in federal prison after pleading guilty to defrauding lenders along with Jack Abramoff, the disgraced lobbyist whose corruption became a symbol of the excesses of Washington influence peddling. He was paroled in 2009, and in 2014 moved his family to a home in Lancaster County, Pa.

The FBI hasn’t responded to LancasterOnline’s tip. Messages sent by KrebsOnSecurity to Kidan’s emails addresses were returned as blocked. Messages left with Mr. Kidan’s company, Empire Workforce Solutions, went unreturned.

No doubt the FBI saw the messages from Kidan for what they likely were: The result of Mr. Kidan having his Microsoft Outlook account compromised and used to send malicious email to people in his contacts list.

Thread hijacking attacks are hardly new, but that is mainly true because many Internet users still don’t know how to identify them. The email security firm Proofpoint says it has tracked north of 90 million malicious messages in the last five years that leverage this attack method.

One key reason thread hijacking is so successful is that these attacks generally do not include the tell that exposes most phishing scams: A fabricated sense of urgency. A majority of phishing threats warn of negative consequences should you fail to act quickly — such as an account suspension or an unauthorized high-dollar charge going through.

In contrast, thread hijacking campaigns tend to patiently prey on the natural curiosity of the recipient.

Ryan Kalember, chief strategy officer at Proofpoint, said probably the most ubiquitous examples of thread hijacking are “CEO fraud” or “business email compromise” scams, wherein employees are tricked by an email from a senior executive into wiring millions of dollars to fraudsters overseas.

But Kalember said these low-tech attacks can nevertheless be quite effective because they tend to catch people off-guard.

“It works because you feel like you’re suddenly included in an important conversation,” Kalember said. “It just registers a lot differently when people start reading, because you think you’re observing a private conversation between two different people.”

Some thread hijacking attacks actually involve multiple threat actors who are actively conversing while copying — but not addressing — the recipient.

“We call these mutli-persona phishing scams, and they’re often paired with thread hijacking,” Kalember said. “It’s basically a way to build a little more affinity than just copying people on an email. And the longer the conversation goes on, the higher their success rate seems to be because some people start replying to the thread [and participating] psycho-socially.”

The best advice to sidestep phishing scams is to avoid clicking on links or attachments that arrive unbidden in emails, text messages and other mediums. If you’re unsure whether the message is legitimate, take a deep breath and visit the site or service in question manually — ideally, using a browser bookmark so as to avoid potential typosquatting sites.