A cyberattack that shut down two of the top casinos in Las Vegas last year quickly became one of the most riveting security stories of 2023: It was the first known case of native English-speaking hackers in the United States and Britain teaming up with ransomware gangs based in Russia. But that made-for-Hollywood narrative has eclipsed a far more hideous trend: Many of these young, Western cybercriminals are also members of fast-growing online groups that exist solely to bully, stalk, harass and extort vulnerable teens into physically harming themselves and others.

Image: Shutterstock.

In September 2023, a Russian ransomware group known as ALPHV/Black Cat claimed credit for an intrusion at the MGM Resorts hotel chain that quickly brought MGM’s casinos in Las Vegas to a standstill. While MGM was still trying to evict the intruders from its systems, an individual who claimed to have firsthand knowledge of the hack contacted multiple media outlets to offer interviews about how it all went down.

One account of the hack came from a 17-year-old in the United Kingdom, who told reporters the intrusion began when one of the English-speaking hackers phoned a tech support person at MGM and tricked them into resetting the password for an employee account.

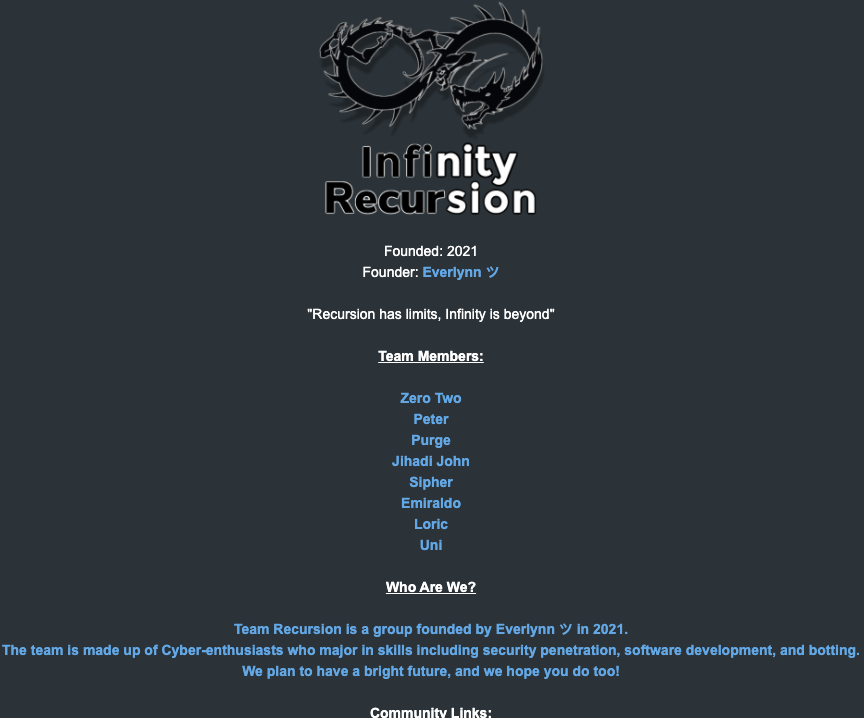

The security firm CrowdStrike dubbed the group “Scattered Spider,” a recognition that the MGM hackers came from different hacker cliques scattered across an ocean of Telegram and Discord servers dedicated to financially-oriented cybercrime.

Collectively, this archipelago of crime-focused chat communities is known as “The Com,” and it functions as a kind of distributed cybercriminal social network that facilitates instant collaboration.

But mostly, The Com is a place where cybercriminals go to boast about their exploits and standing within the community, or to knock others down a peg or two. Top Com members are constantly sniping over who pulled off the most impressive heists, or who has accumulated the biggest pile of stolen virtual currencies.

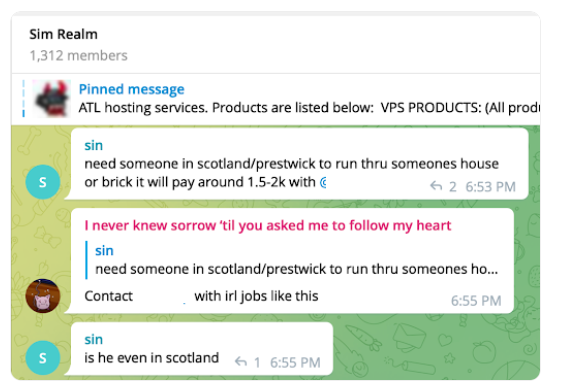

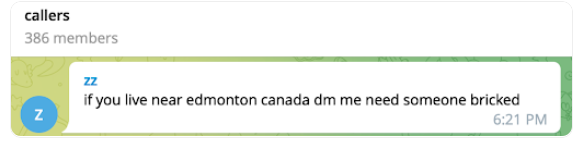

And as often as they extort victim companies for financial gain, members of The Com are constantly trying to wrest stolen money from their cybercriminal rivals — often in ways that spill over into physical violence in the real world.

CrowdStrike would go on to produce and sell Scattered Spider action figures, and it featured a life-sized Scattered Spider sculpture at this year’s RSA Security Conference in San Francisco.

But marketing security products and services based on specific cybercriminal groups can be tricky, particularly if it turns out that robbing and extorting victims is by no means the most abhorrent activity those groups engage in on a daily basis.

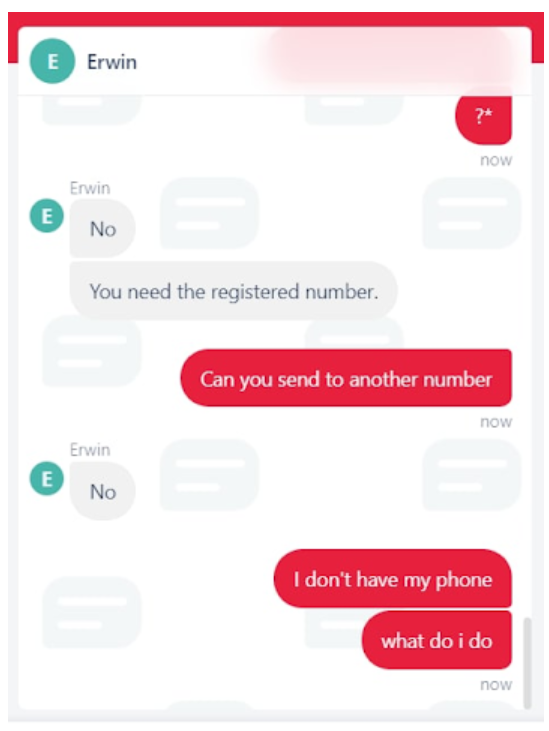

KrebsOnSecurity examined the Telegram user ID number of the account that offered media interviews about the MGM hack — which corresponds to the screen name “@Holy” — and found the same account was used across a number of cybercrime channels that are entirely focused on extorting young people into harming themselves or others, and recording the harm on video.

In one post on a Telegram channel dedicated to youth extortion, this same user can be seen asking if anyone knows the current Telegram handles for several core members of 764, an extremist group known for victimizing children through coordinated online campaigns of extortion, doxing, swatting and harassment.

HOLY NAZI

Holy was known to possess multiple prized Telegram usernames, including @bomb, @halo, and @cute, as well as one of the highest-priced Telegram usernames ever put up for sale: @nazi. A source close to the investigation said @Holy also was a moderator on “Harm Nation,” an offshoot of 764.

People affiliated with harm groups like 764 will often recruit new members by lurking on gaming platforms, social media sites and mobile applications that are popular with young people, including Discord, Minecraft, Roblox, Steam, Telegram, and Twitch.

“This type of offence usually starts with a direct message through gaming platforms and can move to more private chatrooms on other virtual platforms, typically one with video enabled features, where the conversation quickly becomes sexualized or violent,” warns a recent alert from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) about the rise of sextortion groups on social media channels.

“One of the tactics being used by these actors is sextortion, however, they are not using it to extract money or for sexual gratification,” the RCMP continued. “Instead they use it to further manipulate and control victims to produce more harmful and violent content as part of their ideological objectives and radicalization pathway.”

The 764 network is among the most populated harm communities, but there are plenty more. Some of the largest such known groups include CVLT, Court, Kaskar, Leak Society, 7997, 8884, 2992, 6996, 555, Slit Town, 545, 404, NMK, 303, and H3ll.

In March, a consortium of reporters from Wired, Der Spiegel, Recorder and The Washington Post examined millions of messages across more than 50 Discord and Telegram chat groups.

“The abuse perpetrated by members of com groups is extreme,” Wired’s Ali Winston wrote. “They have coerced children into sexual abuse or self-harm, causing them to deeply lacerate their bodies to carve ‘cutsigns’ of an abuser’s online alias into their skin.” The story continues:

“Victims have flushed their heads in toilets, attacked their siblings, killed their pets, and in some extreme instances, attempted or died by suicide. Court records from the United States and European nations reveal participants in this network have also been accused of robberies, in-person sexual abuse of minors, kidnapping, weapons violations, swatting, and murder.”

“Some members of the network extort children for sexual pleasure, some for power and control. Some do it merely for the kick that comes from manipulation. Others sell the explicit CSAM content produced by extortion on the dark web.”

KrebsOnSecurity has learned Holy’s real name is Owen David Flowers, and that he is the previously unnamed 17-year-old who was arrested in July 2024 by the U.K.’s West Midlands Police as part of a joint investigation with the FBI into the MGM hack.

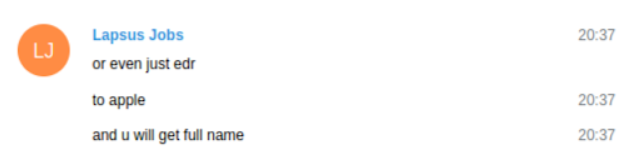

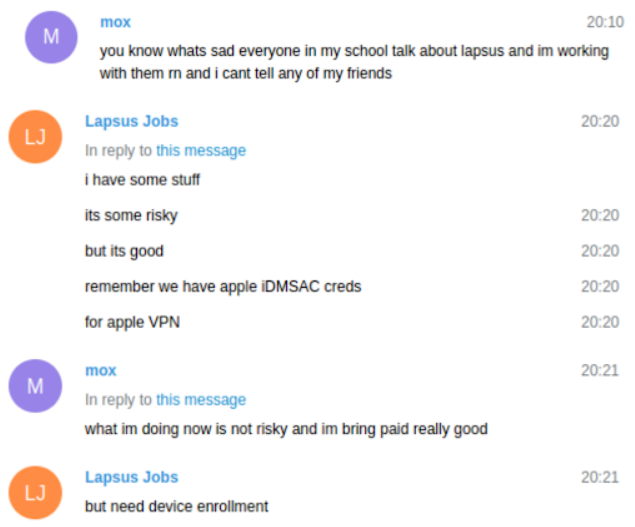

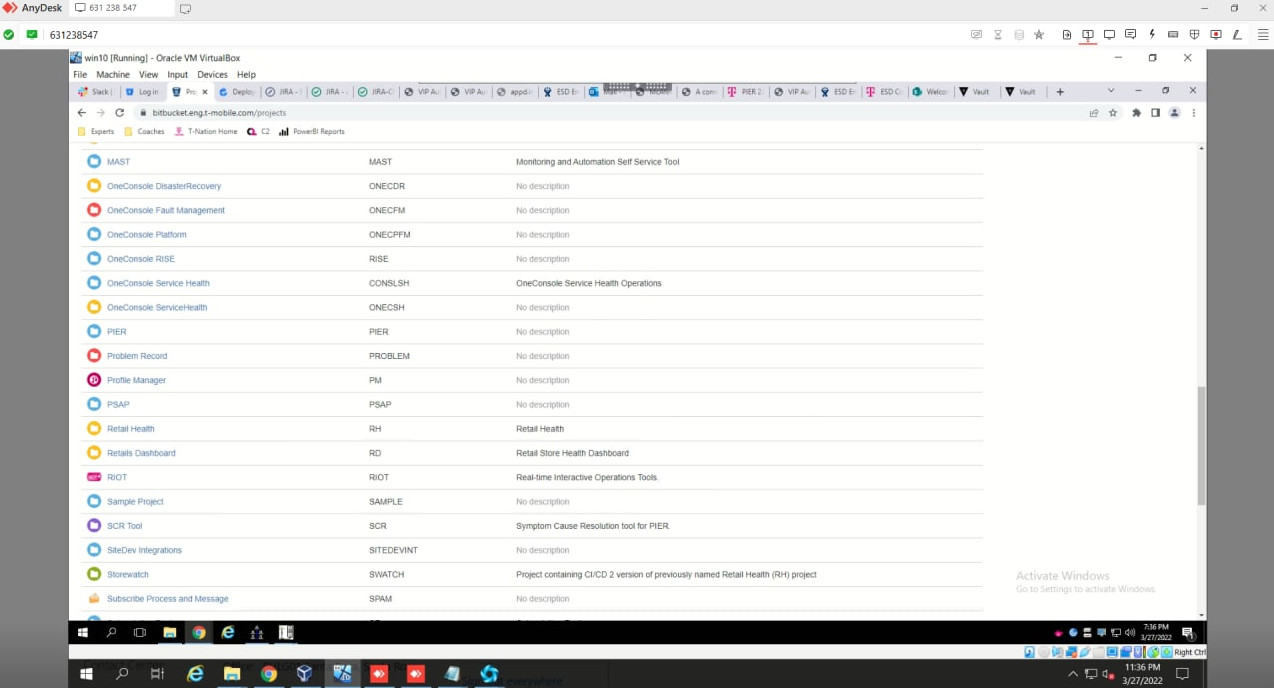

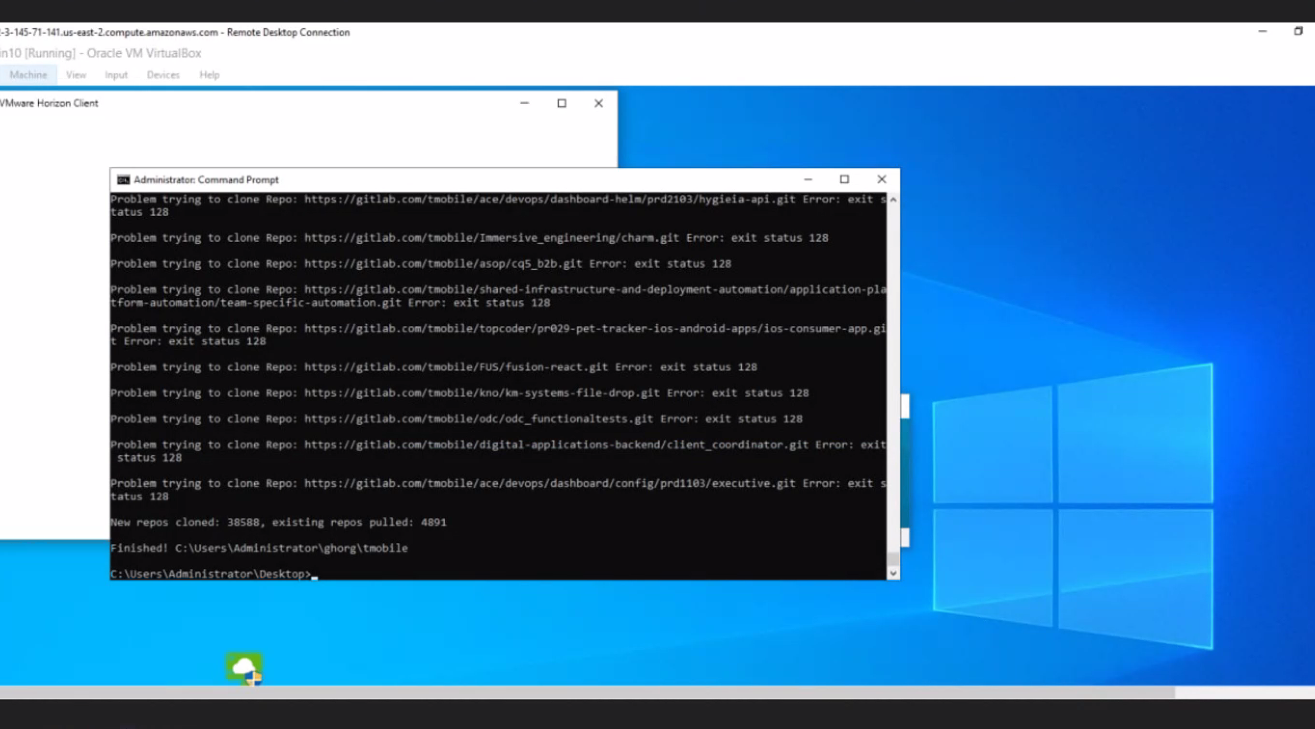

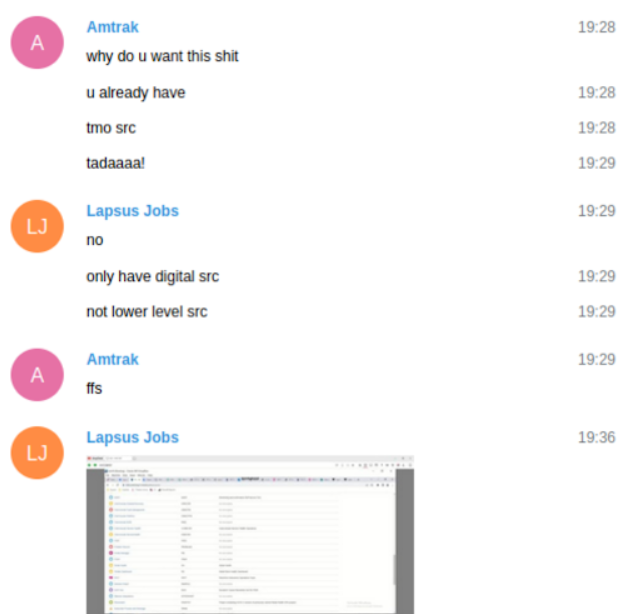

Early in their cybercriminal career (as a 15-year-old), @Holy went by the handle “Vsphere,” and was a proud member of the LAPSUS$ cybercrime group. Throughout 2022, LAPSUS$ would hack and social engineer their way into some of the world’s biggest technology companies, including EA Games, Microsoft, NVIDIA, Okta, Samsung, and T-Mobile.

JUDISCHE/WAIFU

Another timely example of the overlap between harm communities and top members of The Com can be found in a group of criminals who recently stole obscene amounts of customer records from users of the cloud data provider Snowflake.

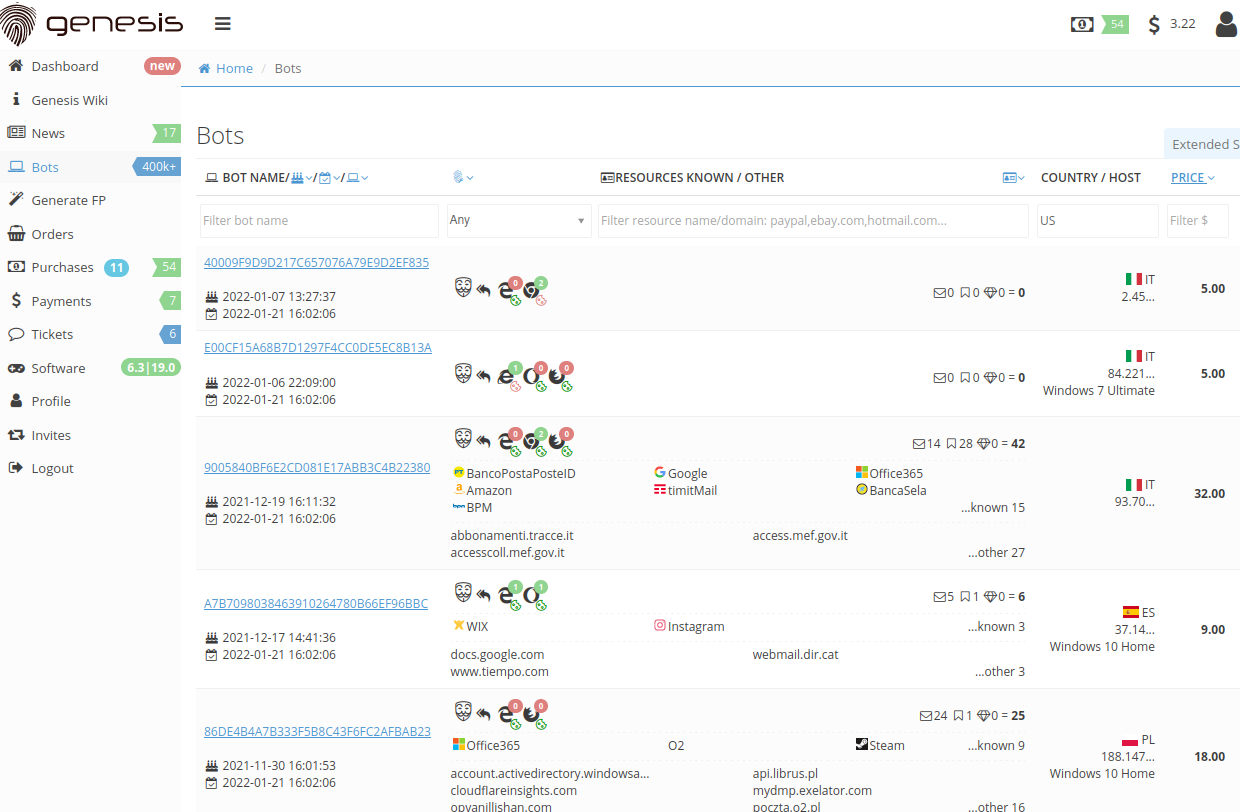

At the end of 2023, malicious hackers figured out that many major companies have uploaded massive amounts of valuable and sensitive customer data to Snowflake servers, all the while protecting those Snowflake accounts with little more than a username and password (no multi-factor authentication required). The group then searched darknet markets for stolen Snowflake account credentials, and began raiding the data storage repositories used by some of the world’s largest corporations.

Among those that had data exposed in Snowflake was AT&T, which disclosed in July that cybercriminals had stolen personal information and phone and text message records for roughly 110 million people — nearly all its customers.

A report on the extortion group from the incident response firm Mandiant notes that Snowflake victim companies were privately approached by the hackers, who demanded a ransom in exchange for a promise not to sell or leak the stolen data. All told, more than 160 organizations were extorted, including TicketMaster, Lending Tree, Advance Auto Parts and Neiman Marcus.

On May 2, 2024, a user by the name “Judische” claimed on the fraud-focused Telegram channel Star Chat that they had hacked Santander Bank, one of the first known Snowflake victims. Judische would repeat that claim in Star Chat on May 13 — the day before Santander publicly disclosed a data breach — and would periodically blurt out the names of other Snowflake victims before their data even went up for sale on the cybercrime forums.

A careful review of Judische’s account history and postings on Telegram shows this user is more widely known under the nickname “Waifu,” an early moniker that corresponds to one of the more accomplished SIM-swappers in The Com over the years.

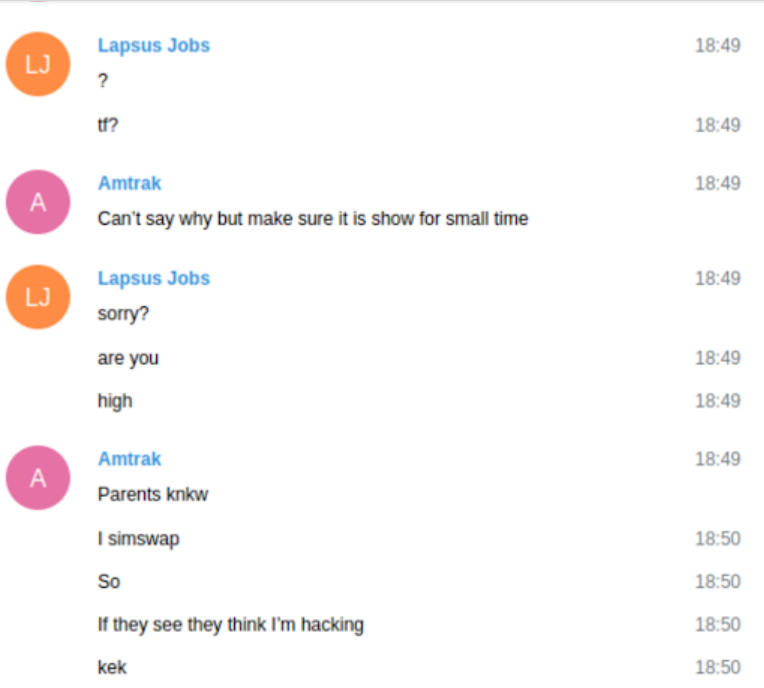

In a SIM-swapping attack, the fraudsters will phish or purchase credentials for mobile phone company employees, and use those credentials to redirect a target’s mobile calls and text messages to a device the attackers control.

Several channels on Telegram maintain a frequently updated leaderboard of the 100 richest SIM-swappers, as well as the hacker handles associated with specific cybercrime groups (Waifu is ranked #24). That leaderboard has long included Waifu on a roster of hackers for a group that called itself “Beige.”

Beige members were implicated in two stories published here in 2020. The first was an August 2020 piece called Voice Phishers Targeting Corporate VPNs, which warned that the COVID-19 epidemic had brought a wave of voice phishing or “vishing” attacks that targeted work-from-home employees via their mobile devices, and tricked many of those people into giving up credentials needed to access their employer’s network remotely.

Beige group members also have claimed credit for a breach at the domain registrar GoDaddy. In November 2020, intruders thought to be associated with the Beige Group tricked a GoDaddy employee into installing malicious software, and with that access they were able to redirect the web and email traffic for multiple cryptocurrency trading platforms.

The Telegram channels that Judische and his related accounts frequented over the years show this user divides their time between posting in SIM-swapping and cybercrime cashout channels, and harassing and stalking others in harm communities like Leak Society and Court.

Mandiant has attributed the Snowflake compromises to a group it calls “UNC5537,” with members based in North America and Turkey. KrebsOnSecurity has learned Judische is a 26-year-old software engineer in Ontario, Canada.

Sources close to the investigation into the Snowflake incident tell KrebsOnSecurity the UNC5537 member in Turkey is John Erin Binns, an elusive American man indicted by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) for a 2021 breach at T-Mobile that exposed the personal information of at least 76.6 million customers.

Binns is currently in custody in a Turkish prison and fighting his extradition. Meanwhile, he has been suing almost every federal agency and agent that contributed investigative resources to his case.

In June 2024, a Mandiant employee told Bloomberg that UNC5537 members have made death threats against cybersecurity experts investigating the hackers, and that in one case the group used artificial intelligence to create fake nude photos of a researcher to harass them.

ViLE

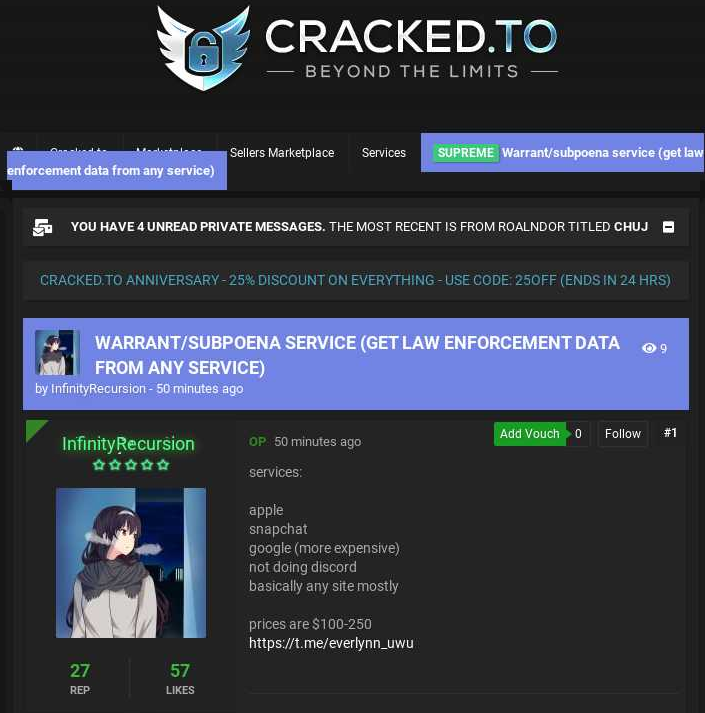

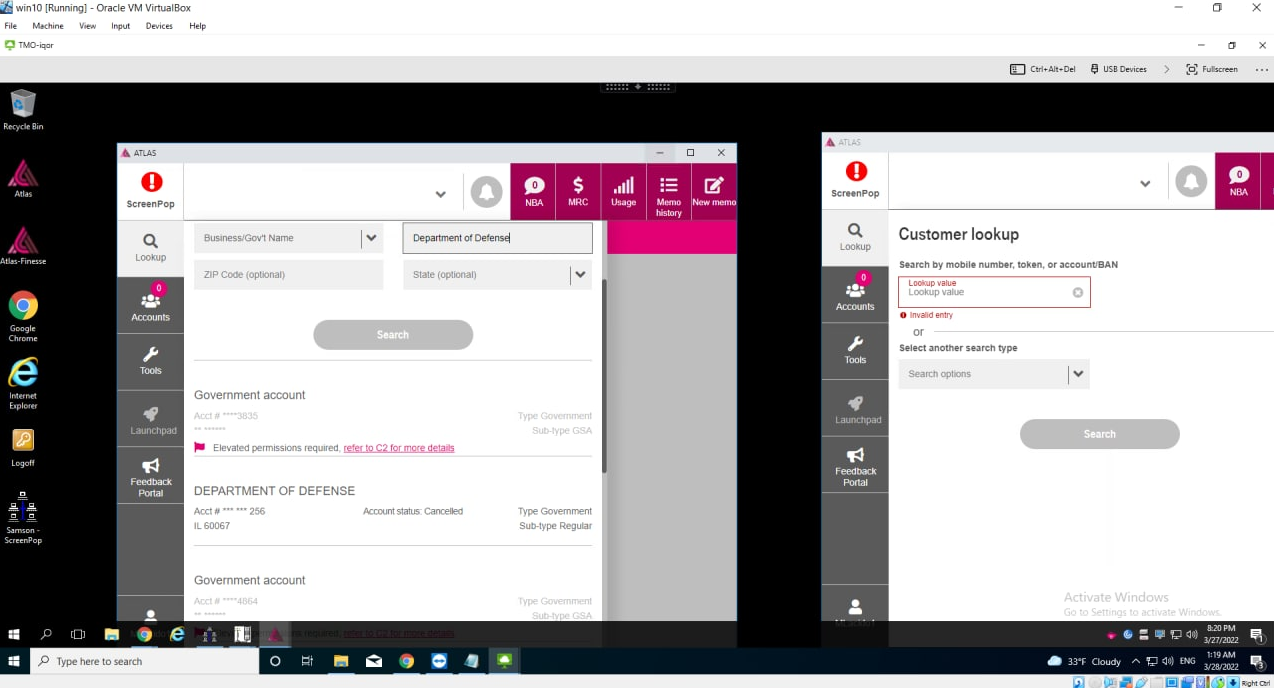

In June 2024, two American men pleaded guilty to hacking into a U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) online portal that tapped into 16 different federal law enforcement databases. Sagar “Weep” Singh, a 20-year-old from Rhode Island, and Nicholas “Convict” Ceraolo, 25, of Queens, NY, were both active in SIM-swapping communities.

Singh and Ceraolo hacked into a number of foreign police department email accounts, and used them to make phony “emergency data requests” to social media platforms seeking account information about specific users they were stalking. According to the government, in each case the men impersonating the foreign police departments told those platforms the request was urgent because the account holders had been trading in child pornography or engaging in child extortion.

Eventually, the two men formed part of a group of cybercriminals known to its members as “ViLE,” who specialize in obtaining personal information about third-party victims, which they then used to harass, threaten or extort the victims, a practice known as “doxing.”

The U.S. government says Singh and Ceraolo worked closely with a third man — referenced in the indictment as co-conspirator #1 or “CC-1” — to administer a doxing forum where victims could pay to have their personal information removed.

The government doesn’t name CC-1 or the doxing forum, but CC-1’s hacker handle is “Kayte” (a.k.a. “KT“) which corresponds to the nickname of a 23-year-old man who lives with his parents in Coffs Harbor, Australia. For several years (with a brief interruption), KT has been the administrator of a truly vile doxing community known as the Doxbin.

A screenshot of the website for the cybercriminal group “ViLE.” Image: USDOJ.

People whose names and personal information appear on the Doxbin can quickly find themselves the target of extended harassment campaigns, account hacking, SIM-swapping and even swatting — which involves falsely reporting a violent incident at a target’s address to trick local police into responding with potentially deadly force.

A handful of Com members targeted by federal authorities have gone so far as to perpetrate swatting, doxing, and other harassment against the same federal agents who are trying to unravel their alleged crimes. This has led some investigators working cases involving the Com to begin redacting their names from affidavits and indictments filed in federal court.

In January 2024, KrebsOnSecurity broke the news that prosecutors in Florida had charged a 19-year-old alleged Scattered Spider member named Noah Michael Urban with wire fraud and identity theft. That story recounted how Urban’s alleged hacker identities “King Bob” and “Sosa” inhabited a world in which rival cryptocurrency theft rings frequently settled disputes through so-called “violence-as-a-service” offerings — hiring strangers online to perpetrate firebombings, beatings and kidnappings against their rivals.

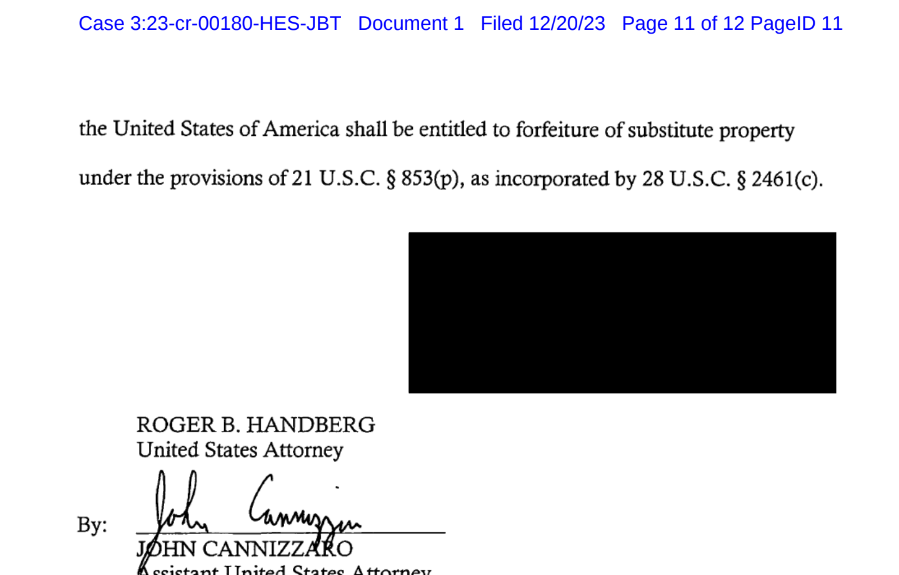

Urban’s indictment is currently sealed. But a copy of the document obtained by KrebsOnSecurity shows the name of the federal agent who testified to it has been blacked out.

The final page of Noah Michael Urban’s indictment shows the investigating agent redacted their name from charging documents.

HACKING RINGS, STALKING VICTIMS

In June 2022, this blog told the story of two men charged with hacking into the Ring home security cameras of a dozen random people and then methodically swatting each of them. Adding insult to injury, the men used the compromised security cameras to record live footage of local police swarming those homes.

McCarty, in a mugshot.

James Thomas Andrew McCarty, Charlotte, N.C., and Kya Christian Nelson, of Racine, Wisc., conspired to hack into Yahoo email accounts belonging to victims in the United States. The two would check how many of those Yahoo accounts were associated with Ring accounts, and then target people who used the same password for both accounts.

The Telegram and Discord aliases allegedly used by McCarty — “Aspertaine” and “Couch,” among others — correspond to an identity that was active in certain channels dedicated to SIM-swapping.

What KrebsOnSecurity didn’t report at the time is that both ChumLul and Aspertaine were active members of CVLT, wherein those identities clearly participated in harassing and exploiting young teens online.

In June 2024, McCarty was sentenced to seven years in prison after pleading guilty to making hoax calls that elicited police SWAT responses. Nelson also pleaded guilty and received a seven-year prison sentence.

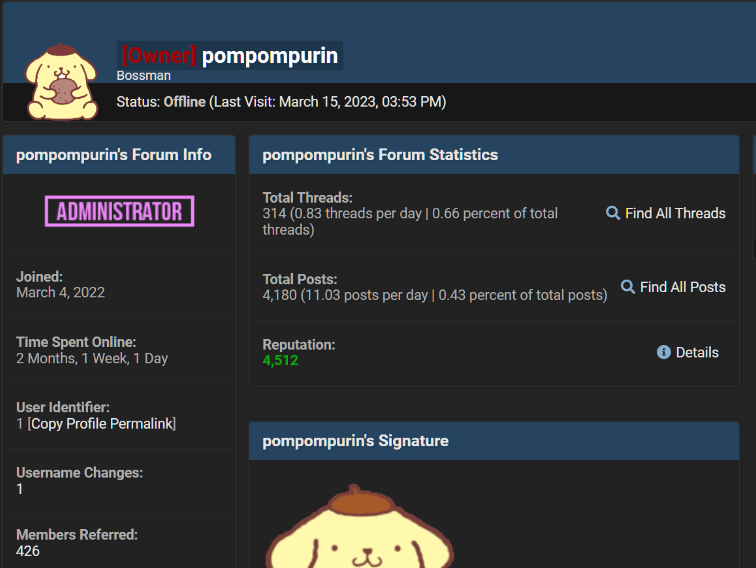

POMPOMPURIN

In March 2023, U.S. federal agents in New York announced they’d arrested “Pompompurin,” the alleged administrator of Breachforums, an English-language cybercrime forum where hacked corporate databases frequently appear for sale. In cases where the victim organization isn’t extorted in advance by hackers, being listed on Breachforums has often been the way many victims first learned of an intrusion.

Pompompurin had been a nemesis to the FBI for several years. In November 2021, KrebsOnSecurity broke the news that thousands of fake emails about a cybercrime investigation were blasted out from the FBI’s email systems and Internet addresses.

Pompompurin took credit for that stunt, and said he was able to send the FBI email blast by exploiting a flaw in an FBI portal designed to share information with state and local law enforcement authorities. The FBI later acknowledged that a software misconfiguration allowed someone to send the fake emails.

In December, 2022, KrebsOnSecurity detailed how hackers active on BreachForums had infiltrated the FBI’s InfraGard program, a vetted network designed to build cyber and physical threat information sharing partnerships with experts in the private sector. The hackers impersonated the CEO of a major financial company, applied for InfraGard membership in the CEO’s name, and were granted admission to the community.

The feds named Pompompurin as 21-year-old Peeksill resident Conor Brian Fitzpatrick, who was originally charged with one count of conspiracy to solicit individuals to sell unauthorized access devices (stolen usernames and passwords). But after FBI agents raided and searched the home where Fitzpatrick lived with his parents, prosecutors tacked on charges for possession of child pornography.

DOMESTIC TERRORISM?

Recent actions by the DOJ indicate the government is well aware of the significant overlap between leading members of The Com and harm communities. But the government also is growing more sensitive to the criticism that it can often take months or years to gather enough evidence to criminally charge some of these suspects, during which time the perpetrators can abuse and recruit countless new victims.

Late last year, however, the DOJ signaled a new tactic in pursuing leaders of harm communities like 764: Charging them with domestic terrorism.

In December 2023, the government charged (PDF) a Hawaiian man with possessing and sharing sexually explicit videos and images of prepubescent children being abused. Prosecutors allege Kalana Limkin, 18, of Hilo, Hawaii, admitted he was an associate of CVLT and 764, and that he was the founder of a splinter harm group called Cultist. Limkin’s Telegram profile shows he also was active on the harm community Slit Town.

The relevant citation from Limkin’s complaint reads:

“Members of the group ‘764’ have conspired and continue to conspire in both online and in-person venues to engage in violent actions in furtherance of a Racially Motivated Violent Extremist ideology, wholly or in part through activities that violate federal criminal law meeting the statutory definition of Domestic Terrorism, defined in Title 18, United States Code, § 2331.”

Experts say charging harm groups under anti-terrorism statutes potentially gives the government access to more expedient investigative powers than it would normally have in a run-of-the-mill criminal hacking case.

“What it ultimately gets you is additional tools you can use in the investigation, possibly warrants and things like that,” said Mark Rasch, a former U.S. federal cybercrime prosecutor and now general counsel for the New York-based cybersecurity firm Unit 221B. “It can also get you additional remedies at the end of the case, like greater sanctions, more jail time, fines and forfeiture.”

But Rasch said this tactic can backfire on prosecutors who overplay their hand and go after someone who ends up challenging the charges in court.

“If you’re going to charge a hacker or pedophile with a crime like terrorism, that’s going to make it harder to get a conviction,” Rasch said. “It adds to the prosecutorial burden and increases the likelihood of getting an acquittal.”

Rasch said it’s unclear where it is appropriate to draw the line in the use of terrorism statutes to disrupt harm groups online, noting that there certainly are circumstances where individuals can commit violations of domestic anti-terrorism statutes through their Internet activity alone.

“The Internet is a platform like any other, where virtually any kind of crime that can be committed in the real world can also be committed online,” he said. “That doesn’t mean all misuse of computers fits within the statutory definition of terrorism.”

The RCMP’s warning on sexual extortion of minors over the Internet lists a number of potential warning signs that teens may exhibit if they become immeshed in these harm groups. The FBI urges anyone who believes their child or someone they know is being exploited to contact their local FBI field office, call 1-800-CALL-FBI, or report it online at tips.fbi.gov.

These so-called Mobile Device Management (MDM) systems retrieve information about the underlying hardware and software powering the system requesting access, and then relay that information along with any login credentials.

These so-called Mobile Device Management (MDM) systems retrieve information about the underlying hardware and software powering the system requesting access, and then relay that information along with any login credentials.