Joseph James “PlugwalkJoe” O’Connor, a 24-year-old from the United Kingdom who earned his 15 minutes of fame by participating in the July 2020 hack of Twitter, has been sentenced to five years in a U.S. prison. That may seem like harsh punishment for a brief and very public cyber joy ride. But O’Connor also pleaded guilty in a separate investigation involving a years-long spree of cyberstalking and cryptocurrency theft enabled by “SIM swapping,” a crime wherein fraudsters trick a mobile provider into diverting a customer’s phone calls and text messages to a device they control.

Joseph “PlugwalkJoe” O’Connor, in a photo from a Globe Newswire press release Sept. 02, 2020, pitching O’Connor as a cryptocurrency expert and advisor.

On July 16, 2020 — the day after some of Twitter’s most recognizable and popular users had their accounts hacked and used to tweet out a bitcoin scam — KrebsOnSecurity observed that several social media accounts tied to O’Connor appeared to have inside knowledge of the intrusion. That story also noted that thanks to COVID-19 lockdowns at the time, O’Connor was stuck on an indefinite vacation at a popular resort in Spain.

Not long after the Twitter hack, O’Connor was quoted in The New York Times denying any involvement. “I don’t care,” O’Connor told The Times. “They can come arrest me. I would laugh at them. I haven’t done anything.”

Speaking with KrebsOnSecurity via Instagram instant message just days after the Twitter hack, PlugwalkJoe demanded that his real name be kept out of future blog posts here. After he was told that couldn’t be promised, he remarked that some people in his circle of friends had been known to hire others to deliver physical beatings on people they didn’t like.

O’Connor was still in Spain a year later when prosecutors in the Northern District of California charged him with conspiring to hack Twitter. At the same time, prosecutors in the Southern District of New York charged O’Connor with an impressive array of cyber offenses involving the exploitation of social media accounts, online extortion, and cyberstalking, and the theft of cryptocurrency then valued at nearly USD $800,000.

In late April 2023, O’Connor was extradited from Spain to face charges in the United States. Two weeks later, he entered guilty pleas in both California and New York, admitting to all ten criminal charges levied against him. On June 23, O’Connor was sentenced to five years in prison.

PlugwalkJoe was part of a community that specialized in SIM-swapping victims to take over their online identities. Unauthorized SIM swapping is a scheme in which fraudsters trick or bribe employees at wireless phone companies into redirecting the target’s text messages and phone calls to a device they control.

From there, the attackers can reset the password for any of the victim’s online accounts that allow password resets via SMS. SIM swapping also lets attackers intercept one-time passwords needed for SMS-based multi-factor authentication (MFA).

O’Connor admitted to conducting SIM swapping attacks to take control over financial accounts tied to several cryptocurrency executives in May 2019, and to stealing digital currency currently valued at more than $1.6 million.

PlugwalkJoe also copped to SIM-swapping his way into the Snapchat accounts of several female celebrities and threatening to release nude photos found on their phones.

Victims who refused to give up social media accounts or submit to extortion demands were often visited with “swatting attacks,” wherein O’Connor and others would falsely report a shooting or hostage situation in the hopes of tricking police into visiting potentially lethal force on a target’s address.

Prosecutors said O’Connor even swatted and cyberstalked a 16-year-old girl, sending her nude photos and threatening to rape and/or murder her and her family.

In the case of the Twitter hack, O’Connor pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit computer intrusions, conspiracy to commit wire fraud, and conspiracy to commit money laundering.

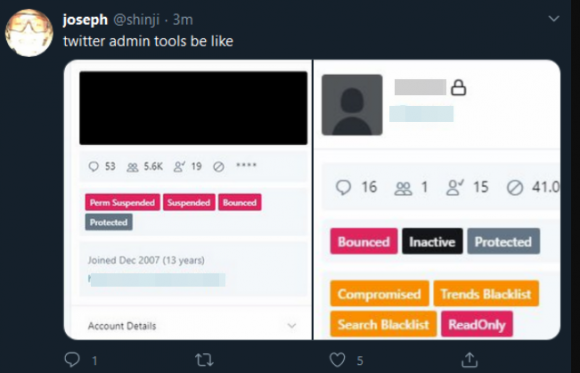

The account “@shinji,” a.k.a. “PlugWalkJoe,” tweeting a screenshot of Twitter’s internal tools interface, on July 15, 2020.

To resolve the case against him in New York, O’Connor pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit computer intrusion, two counts of committing computer intrusions, making extortive communications, two counts of stalking, and making threatening communications.

In addition to the prison term, O’Connor was sentenced to three years of supervised release, and ordered to pay $794,012.64 in forfeiture.

To be clear, the Twitter hack of July 2020 did not involve SIM-swapping. Rather, Twitter said the intruders tricked a Twitter employee over the phone into providing access to internal tools.

Three others were charged along with O’Connor in the Twitter compromise. The alleged mastermind of the hack, then 17-year-old Graham Ivan Clarke from Tampa, Fla., pleaded guilty in 2021 and agreed to serve three years in prison, followed by three years probation.

This story is good reminder about the need to minimize your reliance on the mobile phone companies for securing your online identity. This means reducing the number of ways your life could be turned upside down if someone were to hijack your mobile phone number.

Most online services require users to validate a mobile phone number as part of setting up an account, but some services will let you remove your phone number after the fact. Those services that do you let you remove your phone number or disable SMS/phone calls for account recovery probably also offer more secure multi-factor authentication options, such as app-based one-time passwords and security keys. Check out 2fa.directory for a list of multi-factor options available across hundreds of popular sites and services.