Besieged by scammers seeking to phish user accounts over the telephone, Apple and Google frequently caution that they will never reach out unbidden to users this way. However, new details about the internal operations of a prolific voice phishing gang show the group routinely abuses legitimate services at Apple and Google to force a variety of outbound communications to their users, including emails, automated phone calls and system-level messages sent to all signed-in devices.

Image: Shutterstock, iHaMoo.

KrebsOnSecurity recently told the saga of a cryptocurrency investor named Tony who was robbed of more than $4.7 million in an elaborate voice phishing attack. In Tony’s ordeal, the crooks appear to have initially contacted him via Google Assistant, an AI-based service that can engage in two-way conversations. The phishers also abused legitimate Google services to send Tony an email from google.com, and to send a Google account recovery prompt to all of his signed-in devices.

Today’s story pivots off of Tony’s heist and new details shared by a scammer to explain how these voice phishing groups are abusing a legitimate Apple telephone support line to generate “account confirmation” message prompts from Apple to their customers.

Before we get to the Apple scam in detail, we need to revisit Tony’s case. The phishing domain used to steal roughly $4.7 million in cryptocurrencies from Tony was verify-trezor[.]io. This domain was featured in a writeup from February 2024 by the security firm Lookout, which found it was one of dozens being used by a prolific and audacious voice phishing group it dubbed “Crypto Chameleon.”

Crypto Chameleon was brazenly trying to voice phish employees at the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC), as well as those working at the cryptocurrency exchanges Coinbase and Binance. Lookout researchers discovered multiple voice phishing groups were using a new phishing kit that closely mimicked the single sign-on pages for Okta and other authentication providers.

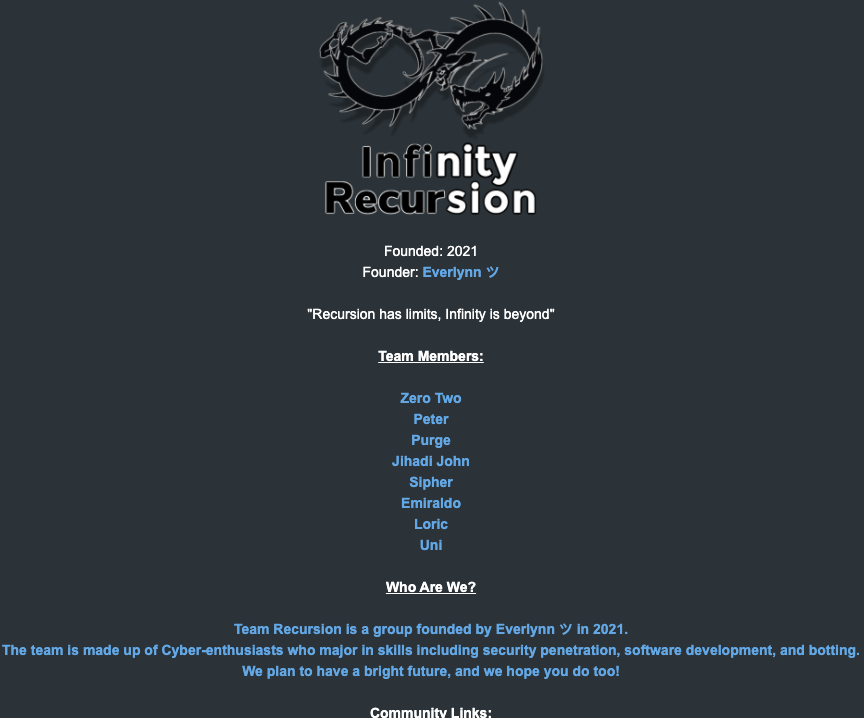

As we’ll see in a moment, that phishing kit is operated and rented out by a cybercriminal known as “Perm” a.k.a. “Annie.” Perm is the current administrator of Star Fraud, one of the more consequential cybercrime communities on Telegram and one that has emerged as a foundry of innovation in voice phishing attacks.

A review of the many messages that Perm posted to Star Fraud and other Telegram channels showed they worked closely with another cybercriminal who went by the handles “Aristotle” and just “Stotle.”

It is not clear what caused the rift, but at some point last year Stotle decided to turn on his erstwhile business partner Perm, sharing extremely detailed videos, tutorials and secrets that shed new light on how these phishing panels operate.

Stotle explained that the division of spoils from each robbery is decided in advance by all participants. Some co-conspirators will be paid a set fee for each call, while others are promised a percentage of any overall amount stolen. The person in charge of managing or renting out the phishing panel to others will generally take a percentage of each theft, which in Perm’s case is 10 percent.

When the phishing group settles on a target of interest, the scammers will create and join a new Discord channel. This allows each logged on member to share what is currently on their screen, and these screens are tiled in a series of boxes so that everyone can see all other call participant screens at once.

Each participant in the call has a specific role, including:

-The Caller: The person speaking and trying to social engineer the target.

-The Operator: The individual managing the phishing panel, silently moving the victim from page to page.

-The Drainer: The person who logs into compromised accounts to drain the victim’s funds.

-The Owner: The phishing panel owner, who will frequently listen in on and participate in scam calls.

‘OKAY, SO THIS REALLY IS APPLE’

In one video of a live voice phishing attack shared by Stotle, scammers using Perm’s panel targeted a musician in California. Throughout the video, we can see Perm monitoring the conversation and operating the phishing panel in the upper right corner of the screen.

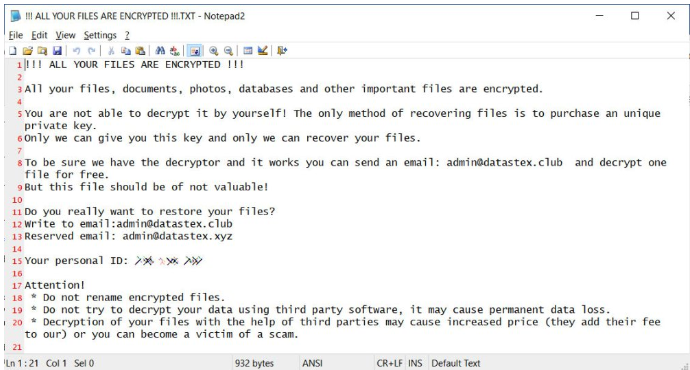

In the first step of the attack, they peppered the target’s Apple device with notifications from Apple by attempting to reset his password. Then a “Michael Keen” called him, spoofing Apple’s phone number and saying they were with Apple’s account recovery team.

The target told Michael that someone was trying to change his password, which Michael calmly explained they would investigate. Michael said he was going to send a prompt to the man’s device, and proceeded to place a call to an automated line that answered as Apple support saying, “I’d like to send a consent notification to your Apple devices. Do I have permission to do that?”

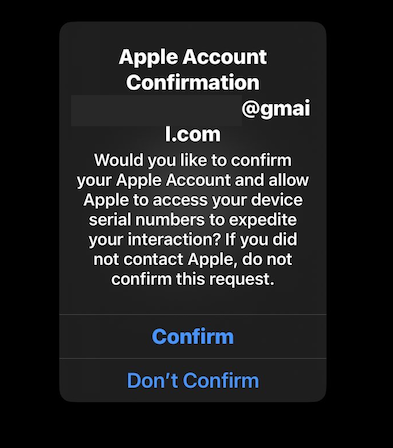

In this segment of the video, we can see the operator of the panel is calling the real Apple customer support phone number 800-275-2273, but they are doing so by spoofing the target’s phone number (the victim’s number is redacted in the video above). That’s because calling this support number from a phone number tied to an Apple account and selecting “1” for “yes” will then send an alert from Apple that displays the following message on all associated devices:

Calling the Apple support number 800-275-2273 from a phone number tied to an Apple account will cause a prompt similar to this one to appear on all connected Apple devices.

KrebsOnSecurity asked two different security firms to test this using the caller ID spoofing service shown in Perm’s video, and sure enough calling that 800 number for Apple by spoofing my phone number as the source caused the Apple Account Confirmation to pop up on all of my signed-in Apple devices.

In essence, the voice phishers are using an automated Apple phone support line to send notifications from Apple and to trick people into thinking they’re really talking with Apple. The phishing panel video leaked by Stotle shows this technique fooled the target, who felt completely at ease that he was talking to Apple after receiving the support prompt on his iPhone.

“Okay, so this really is Apple,” the man said after receiving the alert from Apple. “Yeah, that’s definitely not me trying to reset my password.”

“Not a problem, we can go ahead and take care of this today,” Michael replied. “I’ll go ahead and prompt your device with the steps to close out this ticket. Before I do that, I do highly suggest that you change your password in the settings app of your device.”

The target said they weren’t sure exactly how to do that. Michael replied “no problem,” and then described how to change the account password, which the man said he did on his own device. At this point, the musician was still in control of his iCloud account.

“Password is changed,” the man said. “I don’t know what that was, but I appreciate the call.”

“Yup,” Michael replied, setting up the killer blow. “I’ll go ahead and prompt you with the next step to close out this ticket. Please give me one moment.”

The target then received a text message that referenced information about his account, stating that he was in a support call with Michael. Included in the message was a link to a website that mimicked Apple’s iCloud login page — 17505-apple[.]com. Once the target navigated to the phishing page, the video showed Perm’s screen in the upper right corner opening the phishing page from their end.

“Oh okay, now I log in with my Apple ID?,” the man asked.

“Yup, then just follow the steps it requires, and if you need any help, just let me know,” Michael replied.

As the victim typed in their Apple password and one-time passcode at the fake Apple site, Perm’s screen could be seen in the background logging into the victim’s iCloud account.

It’s unclear whether the phishers were able to steal any cryptocurrency from the victim in this case, who did not respond to requests for comment. However, shortly after this video was recorded, someone leaked several music recordings stolen from the victim’s iCloud account.

At the conclusion of the call, Michael offered to configure the victim’s Apple profile so that any further changes to the account would need to happen in person at a physical Apple store. This appears to be one of several scripted ploys used by these voice phishers to gain and maintain the target’s confidence.

A tutorial shared by Stotle titled “Social Engineering Script” includes a number of tips for scam callers that can help establish trust or a rapport with their prey. When the callers are impersonating Coinbase employees, for example, they will offer to sign the user up for the company’s free security email newsletter.

“Also, for your security, we are able to subscribe you to Coinbase Bytes, which will basically give you updates to your email about data breaches and updates to your Coinbase account,” the script reads. “So we should have gone ahead and successfully subscribed you, and you should have gotten an email confirmation. Please let me know if that is the case. Alright, perfect.”

In reality, all they are doing is entering the target’s email address into Coinbase’s public email newsletter signup page, but it’s a remarkably effective technique because it demonstrates to the would-be victim that the caller has the ability to send emails from Coinbase.com.

Asked to comment for this story, Apple said there has been no breach, hack, or technical exploit of iCloud or Apple services, and that the company is continuously adding new protections to address new and emerging threats. For example, it said it has implemented rate limiting for multi-factor authentication requests, which have been abused by voice phishing groups to impersonate Apple.

Apple said its representatives will never ask users to provide their password, device passcode, or two-factor authentication code or to enter it into a web page, even if it looks like an official Apple website. If a user receives a message or call that claims to be from Apple, here is what the user should expect.

AUTODOXERS

According to Stotle, the target lists used by their phishing callers originate mostly from a few crypto-related data breaches, including the 2022 and 2024 breaches involving user account data stolen from cryptocurrency hardware wallet vendor Trezor.

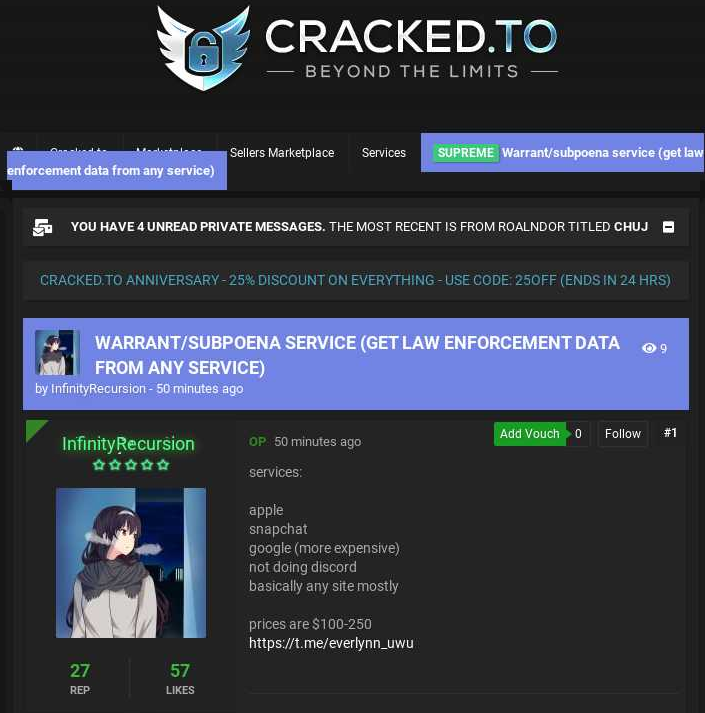

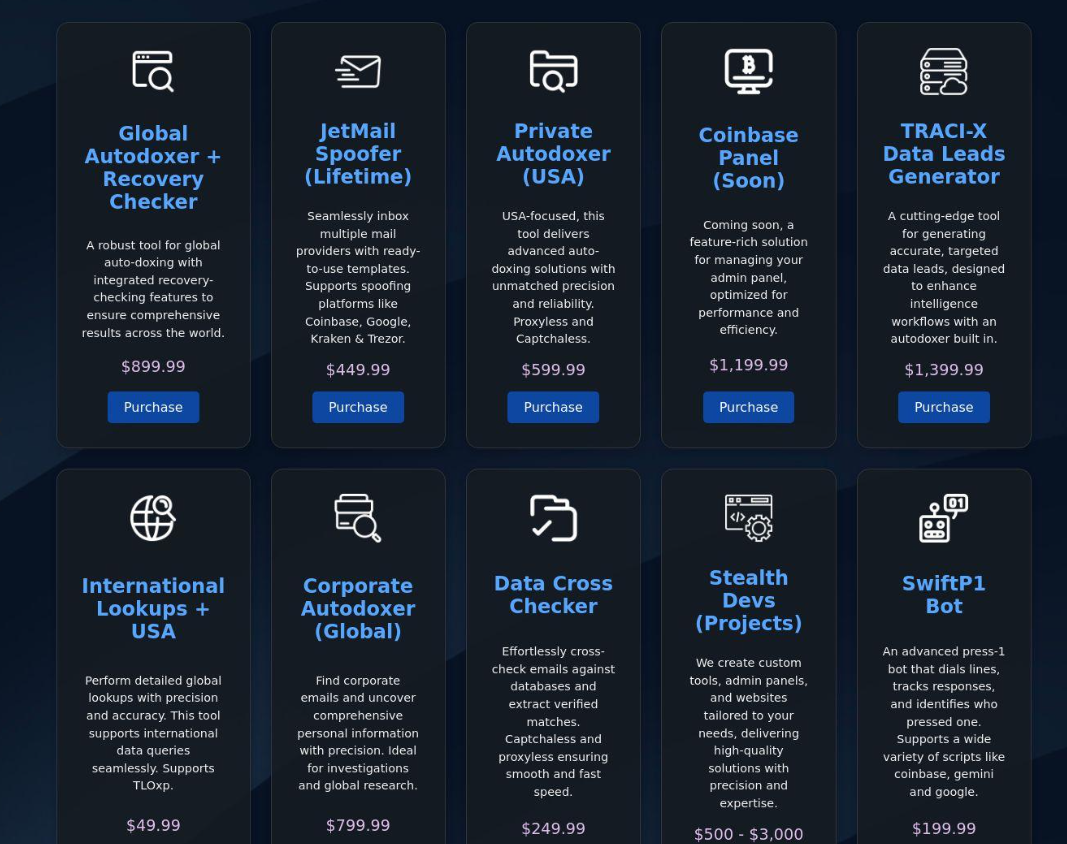

Perm’s group and other crypto phishing gangs rely on a mix of homemade code and third-party data broker services to refine their target lists. Known as “autodoxers,” these tools help phishing gangs quickly automate the acquisition and/or verification of personal data on a target prior to each call attempt.

One “autodoxer” service advertised on Telegram that promotes a range of voice phishing tools and services.

Stotle said their autodoxer used a Telegram bot that leverages hacked accounts at consumer data brokers to gather a wealth of information about their targets, including their full Social Security number, date of birth, current and previous addresses, employer, and the names of family members.

The autodoxers are used to verify that each email address on a target list has an active account at Coinbase or another cryptocurrency exchange, ensuring that the attackers don’t waste time calling people who have no cryptocurrency to steal.

Some of these autodoxer tools also will check the value of the target’s home address at property search services online, and then sort the target lists so that the wealthiest are at the top.

CRYPTO THIEVES IN THE SHARK TANK

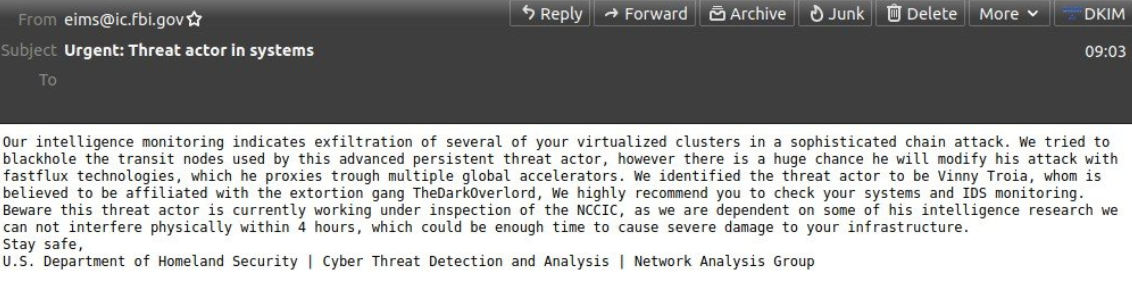

Stotle’s messages on Discord and Telegram show that a phishing group renting Perm’s panel voice-phished tens of thousands of dollars worth of cryptocurrency from the billionaire Mark Cuban.

“I was an idiot,” Cuban told KrebsOnsecurity when asked about the June 2024 attack, which he first disclosed in a short-lived post on Twitter/X. “We were shooting Shark Tank and I was rushing between pitches.”

Image: Shutterstock, ssi77.

Cuban said he first received a notice from Google that someone had tried to log in to his account. Then he got a call from what appeared to be a Google phone number. Cuban said he ignored several of these emails and calls until he decided they probably wouldn’t stop unless he answered.

“So I answered, and wasn’t paying enough attention,” he said. “They asked for the circled number that comes up on the screen. Like a moron, I gave it to them, and they were in.”

Unfortunately for Cuban, somewhere in his inbox were the secret “seed phrases” protecting two of his cryptocurrency accounts, and armed with those credentials the crooks were able to drain his funds. All told, the thieves managed to steal roughly $43,000 worth of cryptocurrencies from Cuban’s wallets — a relatively small heist for this crew.

“They must have done some keyword searches,” once inside his Gmail account, Cuban said. “I had sent myself an email I had forgotten about that had my seed words for 2 accounts that weren’t very active any longer. I had moved almost everything but some smaller balances to Coinbase.”

LIFE IS A GAME: MONEY IS HOW WE KEEP SCORE

Cybercriminals involved in voice phishing communities on Telegram are universally obsessed with their crypto holdings, mainly because in this community one’s demonstrable wealth is primarily what confers social status. It is not uncommon to see members sizing one another up using a verbal shorthand of “figs,” as in figures of crypto wealth.

For example, a low-level caller with no experience will sometimes be mockingly referred to as a 3fig or 3f, as in a person with less than $1,000 to their name. Salaries for callers are often also referenced this way, e.g. “Weekly salary: 5f.”

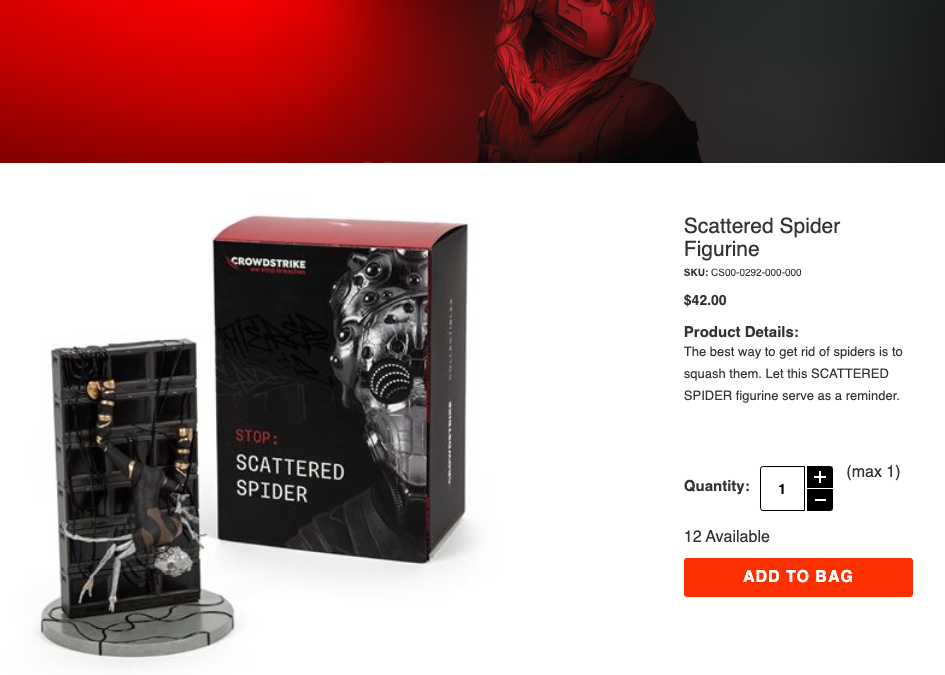

This meme shared by Stotle uses humor to depict and all-too-common pathway for voice phishing callers, who are often minors recruited from gaming networks like Minecraft and Roblox. The image that Lookout used in its blog post for Crypto Chameleon can be seen in the lower right hooded figure.

Voice phishing groups frequently require new members to provide “proof of funds” — screenshots of their crypto holdings, ostensibly to demonstrate they are not penniless — before they’re allowed to join.

This proof of funds (POF) demand is typical among thieves selling high-dollar items, because it tends to cut down on the time-wasting inquiries from criminals who can’t afford what’s for sale anyway. But it has become so common in cybercrime communities that there are now several services designed to create fake POF images and videos, allowing customers to brag about large crypto holdings without actually possessing said wealth.

Several of the phishing panel videos shared by Stotle feature audio that suggests co-conspirators were practicing responses to certain call scenarios, while other members of the phishing group critiqued them or tried disrupt their social engineering by being verbally abusive.

These groups will organize and operate for a few weeks, but tend to disintegrate when one member of the conspiracy decides to steal some or all of the loot, referred to in these communities as “snaking” others out of their agreed-upon sums. Almost invariably, the phishing groups will splinter apart over the drama caused by one of these snaking events, and individual members eventually will then re-form a new phishing group.

Allison Nixon is the chief research officer for Unit 221B, a cybersecurity firm in New York that has worked on a number of investigations involving these voice phishing groups. Nixon said the constant snaking within the voice phishing circles points to a psychological self-selection phenomenon that is in desperate need of academic study.

“In short, a person whose moral compass lets them rob old people will also be a bad business partner,” Nixon said. “This is another fundamental flaw in this ecosystem and why most groups end in betrayal. This structural problem is great for journalists and the police too. Lots of snitching.”

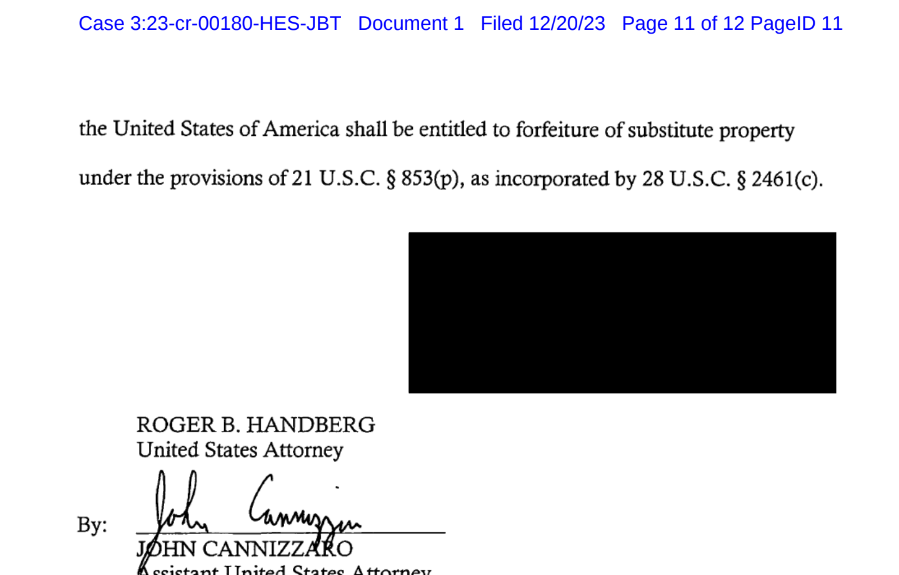

POINTS FOR BRAZENNESS

Asked about the size of Perm’s phishing enterprise, Stotle said there were dozens of distinct phishing groups paying to use Perm’s panel. He said each group was assigned their own subdomain on Perm’s main “command and control server,” which naturally uses the domain name commandandcontrolserver[.]com.

A review of that domain’s history via DomainTools.com shows there are at least 57 separate subdomains scattered across commandandcontrolserver[.]com and two other related control domains — thebackendserver[.]com and lookoutsucks[.]com. That latter domain was created and deployed shortly after Lookout published its blog post on Crypto Chameleon.

The dozens of phishing domains that phone home to these control servers are all kept offline when they are not actively being used in phishing attacks. A social engineering training guide shared by Stotle explains this practice minimizes the chances that a phishing domain will get “redpaged,” a reference to the default red warning pages served by Google Chrome or Firefox whenever someone tries to visit a site that’s been flagged for phishing or distributing malware.

What’s more, while the phishing sites are live their operators typically place a CAPTCHA challenge in front of the main page to prevent security services from scanning and flagging the sites as malicious.

It may seem odd that so many cybercriminal groups operate so openly on instant collaboration networks like Telegram and Discord. After all, this blog is replete with stories about cybercriminals getting caught thanks to personal details they inadvertently leaked or disclosed themselves.

Nixon said the relative openness of these cybercrime communities makes them inherently risky, but it also allows for the rapid formation and recruitment of new potential co-conspirators. Moreover, today’s English-speaking cybercriminals tend to be more afraid of gettimg home invaded or mugged by fellow cyber thieves than they are of being arrested by authorities.

“The biggest structural threat to the online criminal ecosystem is not the police or researchers, it is fellow criminals,” Nixon said. “To protect them from themselves, every criminal forum and marketplace has a reputation system, even though they know it’s a major liability when the police come. That is why I am not worried as we see criminals migrate to various ‘encrypted’ platforms that promise to ignore the police. To protect themselves better against the law, they have to ditch their protections against fellow criminals and that’s not going to happen.”