There are indications that U.S. healthcare giant Change Healthcare has made a $22 million extortion payment to the infamous BlackCat ransomware group (a.k.a. “ALPHV“) as the company struggles to bring services back online amid a cyberattack that has disrupted prescription drug services nationwide for weeks. However, the cybercriminal who claims to have given BlackCat access to Change’s network says the crime gang cheated them out of their share of the ransom, and that they still have the sensitive data Change reportedly paid the group to destroy. Meanwhile, the affiliate’s disclosure appears to have prompted BlackCat to cease operations entirely.

Image: Varonis.

In the third week of February, a cyber intrusion at Change Healthcare began shutting down important healthcare services as company systems were taken offline. It soon emerged that BlackCat was behind the attack, which has disrupted the delivery of prescription drugs for hospitals and pharmacies nationwide for nearly two weeks.

On March 1, a cryptocurrency address that security researchers had already mapped to BlackCat received a single transaction worth approximately $22 million. On March 3, a BlackCat affiliate posted a complaint to the exclusive Russian-language ransomware forum Ramp saying that Change Healthcare had paid a $22 million ransom for a decryption key, and to prevent four terabytes of stolen data from being published online.

The affiliate claimed BlackCat/ALPHV took the $22 million payment but never paid him his percentage of the ransom. BlackCat is known as a “ransomware-as-service” collective, meaning they rely on freelancers or affiliates to infect new networks with their ransomware. And those affiliates in turn earn commissions ranging from 60 to 90 percent of any ransom amount paid.

“But after receiving the payment ALPHV team decide to suspend our account and keep lying and delaying when we contacted ALPHV admin,” the affiliate “Notchy” wrote. “Sadly for Change Healthcare, their data [is] still with us.”

Change Healthcare has neither confirmed nor denied paying, and has responded to multiple media outlets with a similar non-denial statement — that the company is focused on its investigation and on restoring services.

Assuming Change Healthcare did pay to keep their data from being published, that strategy seems to have gone awry: Notchy said the list of affected Change Healthcare partners they’d stolen sensitive data from included Medicare and a host of other major insurance and pharmacy networks.

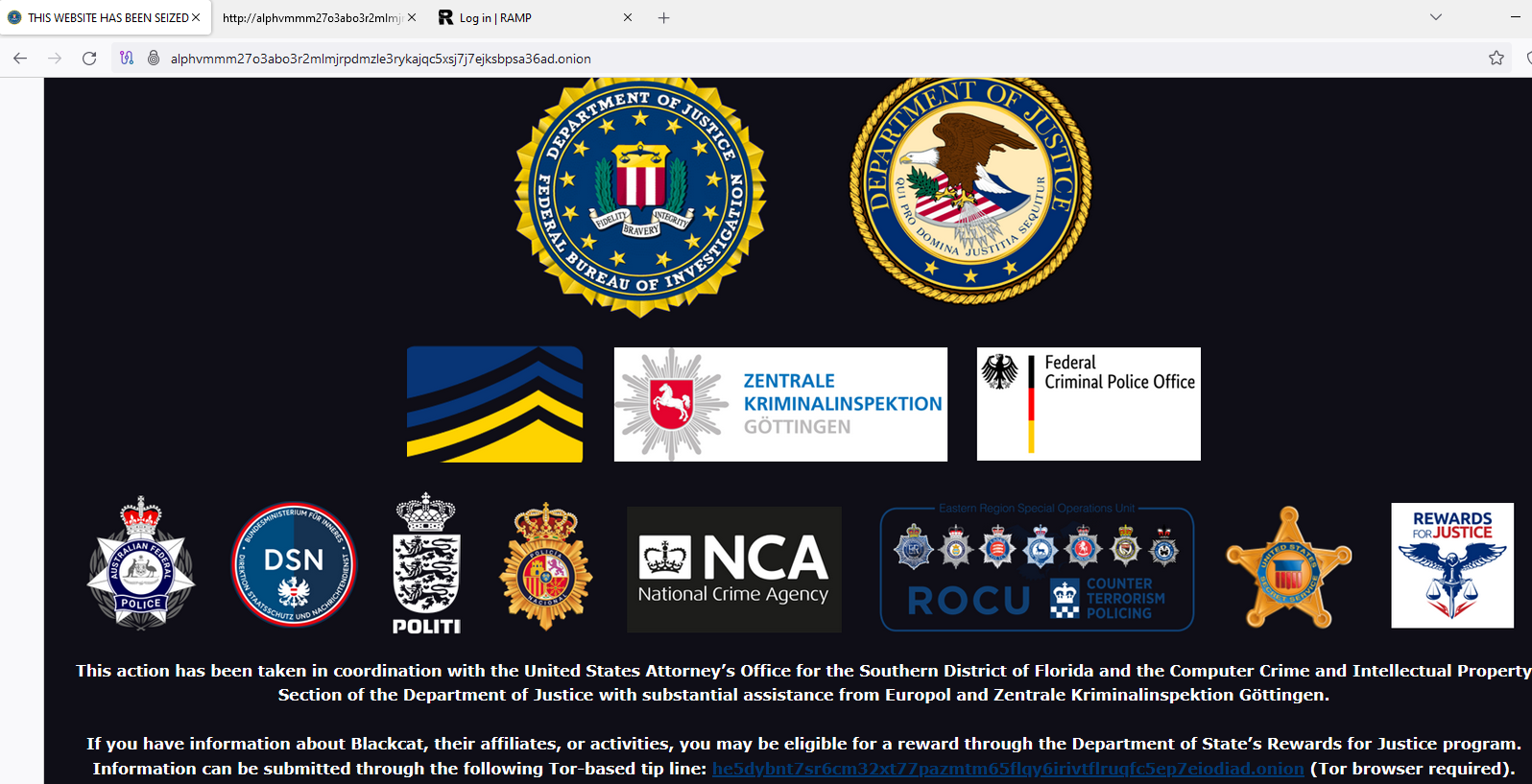

On the bright side, Notchy’s complaint seems to have been the final nail in the coffin for the BlackCat ransomware group, which was infiltrated by the FBI and foreign law enforcement partners in late December 2023. As part of that action, the government seized the BlackCat website and released a decryption tool to help victims recover their systems.

BlackCat responded by re-forming, and increasing affiliate commissions to as much as 90 percent. The ransomware group also declared it was formally removing any restrictions or discouragement against targeting hospitals and healthcare providers.

However, instead of responding that they would compensate and placate Notchy, a representative for BlackCat said today the group was shutting down and that it had already found a buyer for its ransomware source code.

The seizure notice now displayed on the BlackCat darknet website.

“There’s no sense in making excuses,” wrote the RAMP member “Ransom.” “Yes, we knew about the problem, and we were trying to solve it. We told the affiliate to wait. We could send you our private chat logs where we are shocked by everything that’s happening and are trying to solve the issue with the transactions by using a higher fee, but there’s no sense in doing that because we decided to fully close the project. We can officially state that we got screwed by the feds.”

BlackCat’s website now features a seizure notice from the FBI, but several researchers noted that this image seems to have been merely cut and pasted from the notice the FBI left in its December raid of BlackCat’s network. The FBI has not responded to requests for comment.

Fabian Wosar, head of ransomware research at the security firm Emsisoft, said it appears BlackCat leaders are trying to pull an “exit scam” on affiliates by withholding many ransomware payment commissions at once and shutting down the service.

“ALPHV/BlackCat did not get seized,” Wosar wrote on Twitter/X today. “They are exit scamming their affiliates. It is blatantly obvious when you check the source code of their new takedown notice.”

Dmitry Smilyanets, a researcher for the security firm Recorded Future, said BlackCat’s exit scam was especially dangerous because the affiliate still has all the stolen data, and could still demand additional payment or leak the information on his own.

“The affiliates still have this data, and they’re mad they didn’t receive this money, Smilyanets told Wired.com. “It’s a good lesson for everyone. You cannot trust criminals; their word is worth nothing.”

BlackCat’s apparent demise comes closely on the heels of the implosion of another major ransomware group — LockBit, a ransomware gang estimated to have extorted over $120 million in payments from more than 2,000 victims worldwide. On Feb. 20, LockBit’s website was seized by the FBI and the U.K.’s National Crime Agency (NCA) following a months-long infiltration of the group.

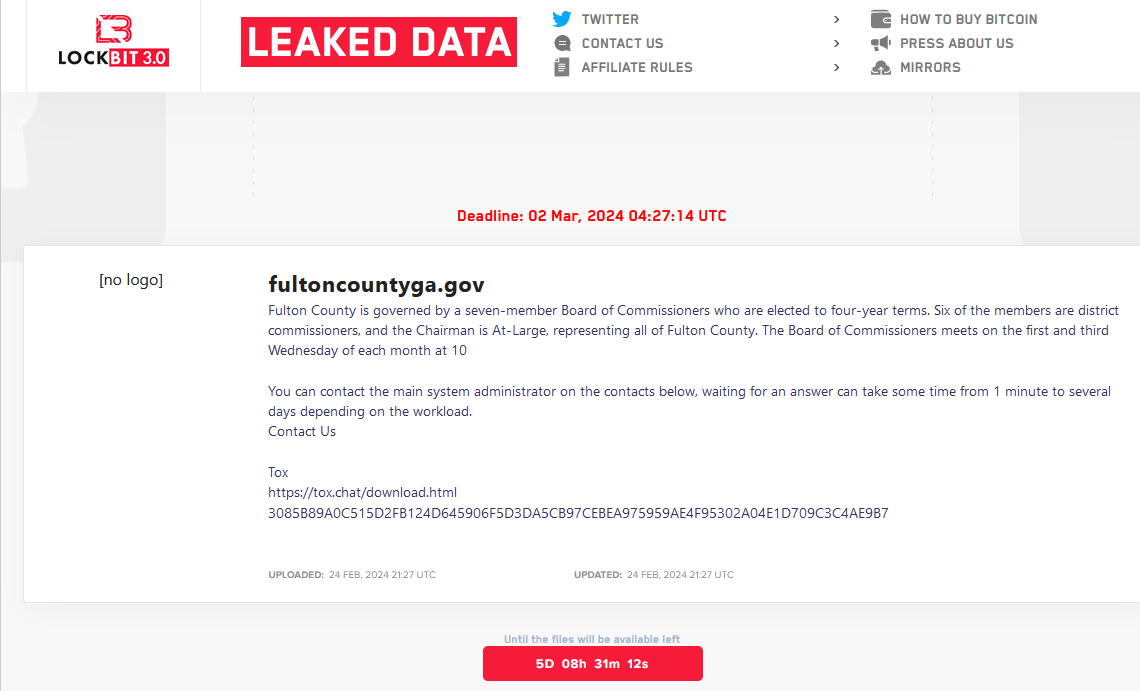

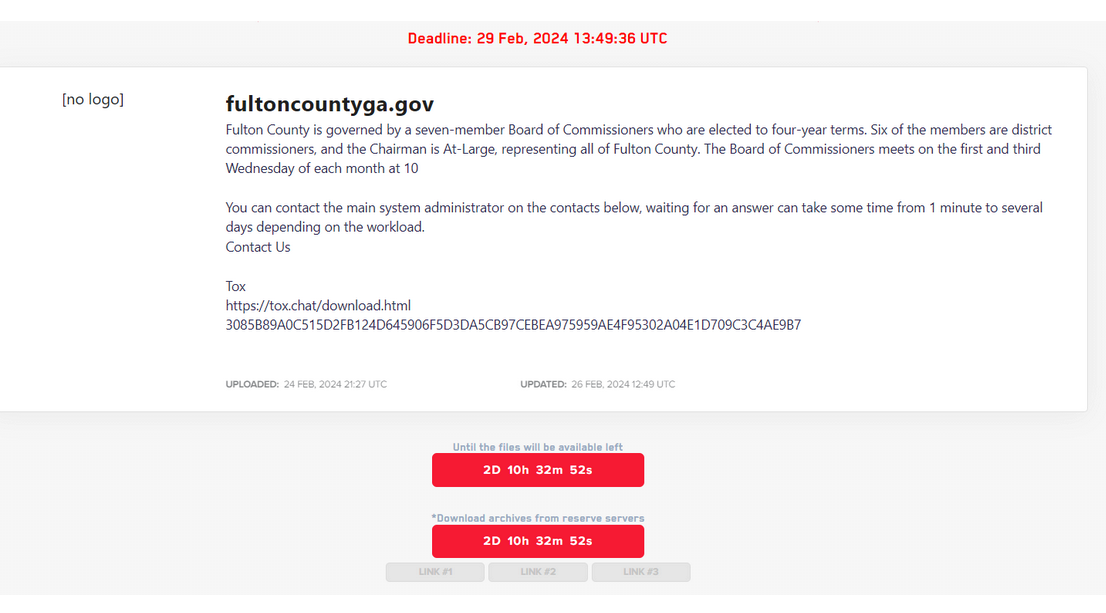

LockBit also tried to restore its reputation on the cybercrime forums by resurrecting itself at a new darknet website, and by threatening to release data from a number of major companies that were hacked by the group in the weeks and days prior to the FBI takedown.

But LockBit appears to have since lost any credibility the group may have once had. After a much-promoted attack on the government of Fulton County, Ga., for example, LockBit threatened to release Fulton County’s data unless paid a ransom by Feb. 29. But when Feb. 29 rolled out, LockBit simply deleted the entry for Fulton County from its site, along with those of several financial organizations that had previously been extorted by the group.

Fulton County held a press conference to say that it had not paid a ransom to LockBit, nor had anyone done so on their behalf, and that they were just as mystified as everyone else as to why LockBit never followed through on its threat to publish the county’s data. Exerts told KrebsOnSecurity LockBit likely balked because it was bluffing, and that the FBI likely relieved them of that data in their raid.

Smilyanets’ comments are driven home in revelations first published last month by Recorded Future, which quoted an NCA official as saying LockBit never deleted the data after being paid a ransom, even though that is the only reason many of its victims paid.

“If we do not give you decrypters, or we do not delete your data after payment, then nobody will pay us in the future,” LockBit’s extortion notes typically read.

Hopefully, more companies are starting to get the memo that paying cybercrooks to delete stolen data is a losing proposition all around.

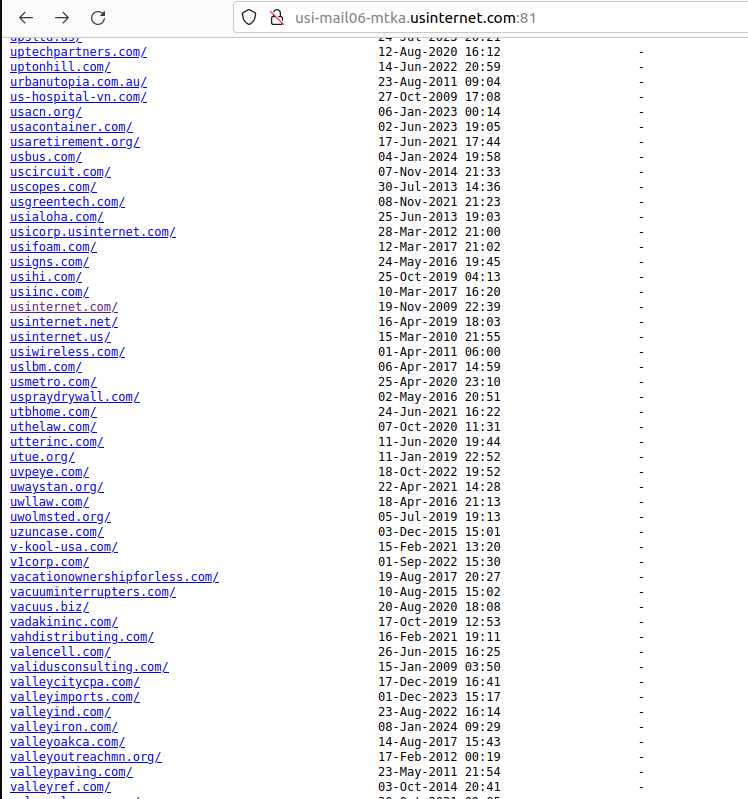

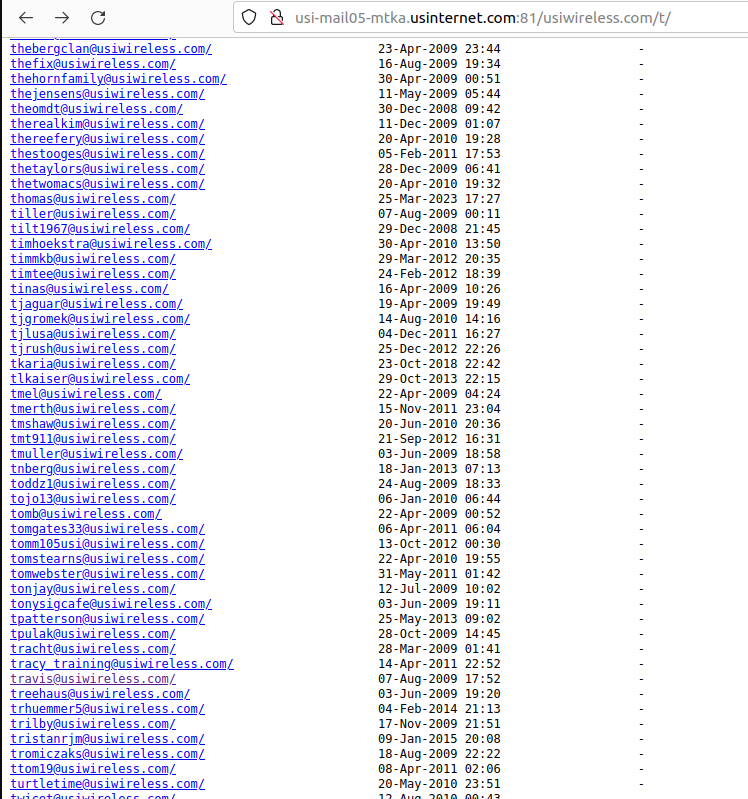

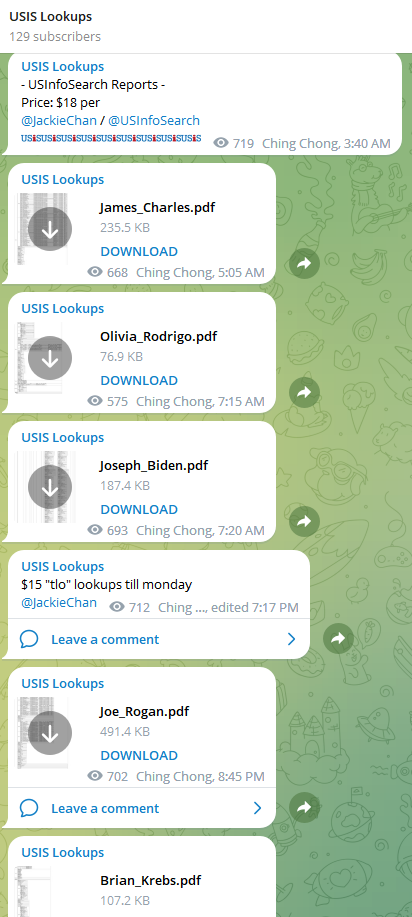

Since at least February 2023, a service advertised on Telegram called USiSLookups has operated an automated bot that allows anyone to look up the SSN or background report on virtually any American. For prices ranging from $8 to $40 and payable via virtual currency, the bot will return detailed consumer background reports automatically in just a few moments.

Since at least February 2023, a service advertised on Telegram called USiSLookups has operated an automated bot that allows anyone to look up the SSN or background report on virtually any American. For prices ranging from $8 to $40 and payable via virtual currency, the bot will return detailed consumer background reports automatically in just a few moments.