Phishers are enjoying remarkable success using text messages to steal remote access credentials and one-time passcodes from employees at some of the world’s largest technology companies and customer support firms. A recent spate of SMS phishing attacks from one cybercriminal group has spawned a flurry of breach disclosures from affected companies, which are all struggling to combat the same lingering security threat: The ability of scammers to interact directly with employees through their mobile devices.

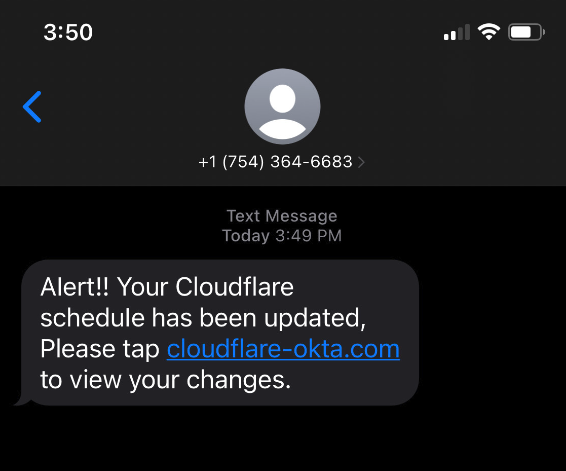

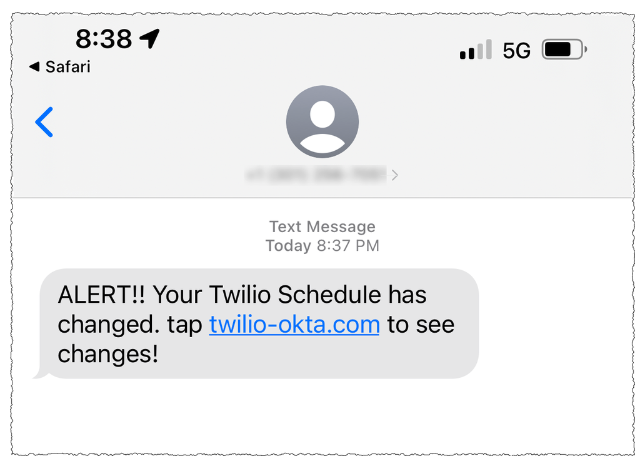

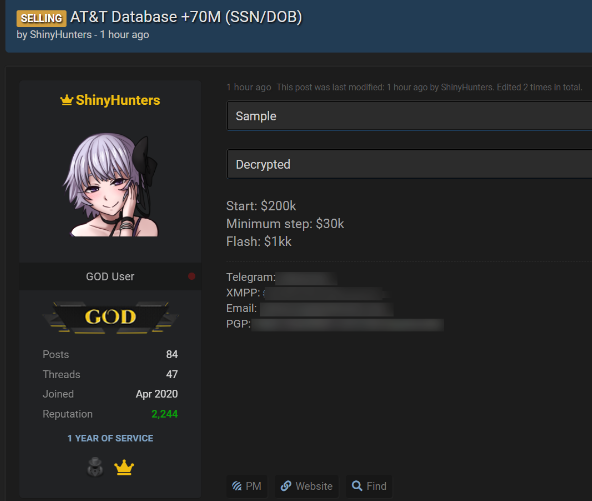

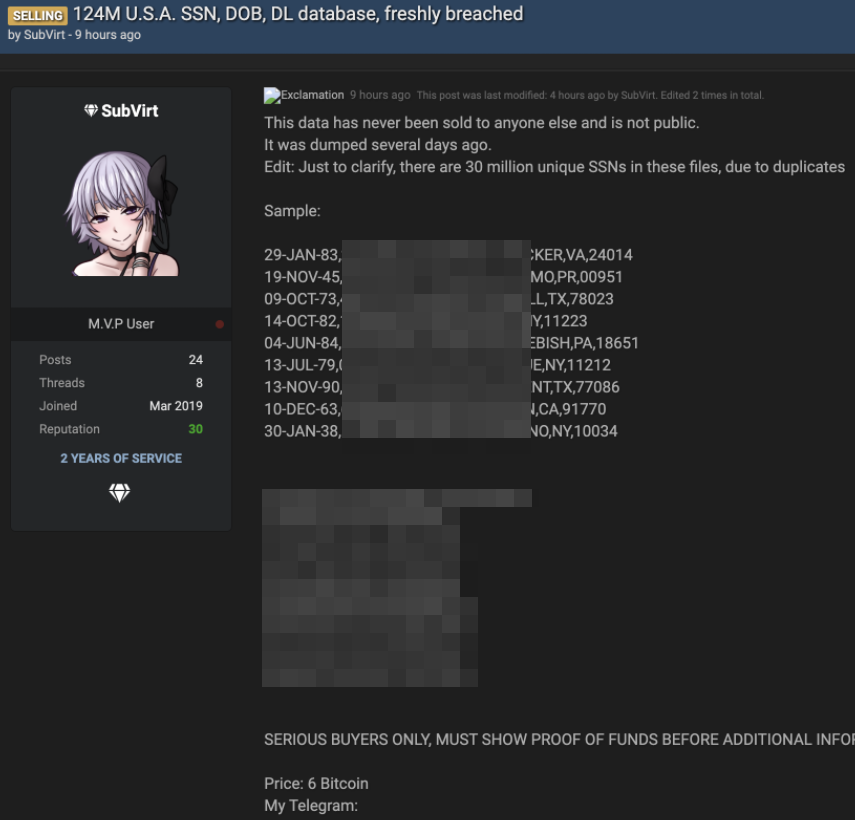

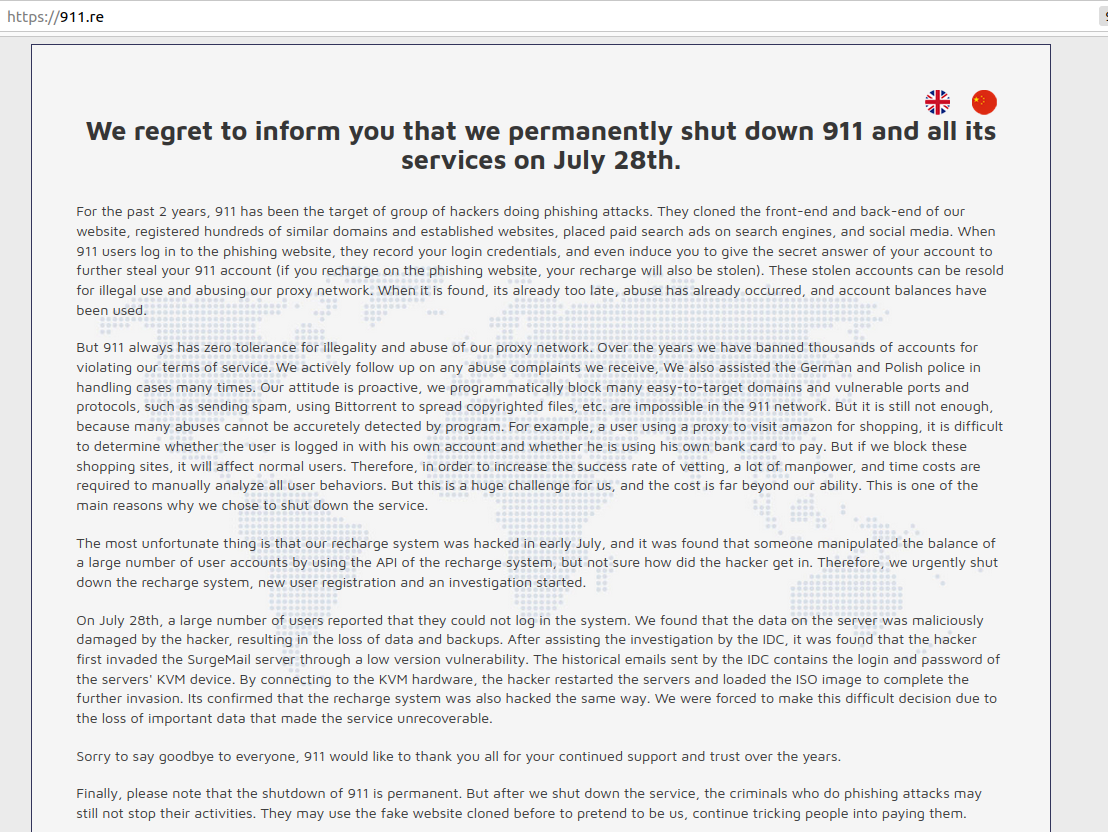

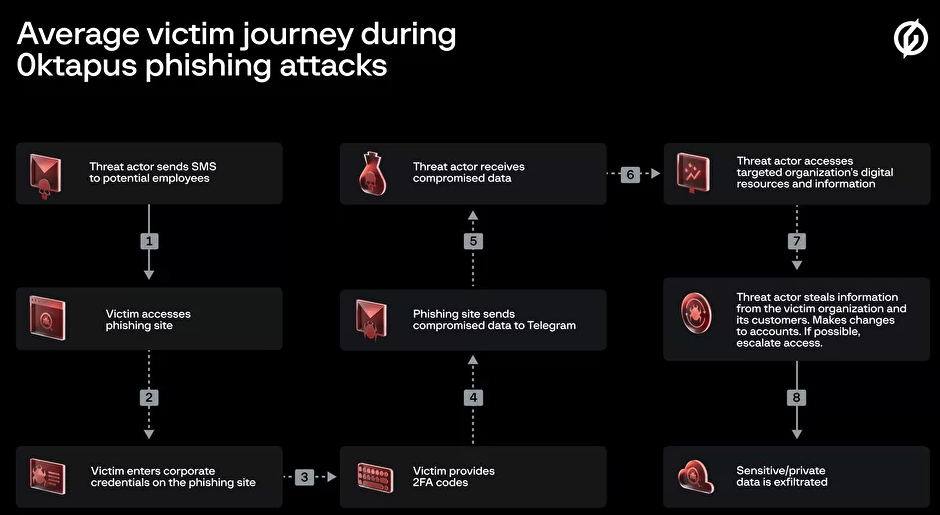

In mid-June 2022, a flood of SMS phishing messages began targeting employees at commercial staffing firms that provide customer support and outsourcing to thousands of companies. The missives asked users to click a link and log in at a phishing page that mimicked their employer’s Okta authentication page. Those who submitted credentials were then prompted to provide the one-time password needed for multi-factor authentication.

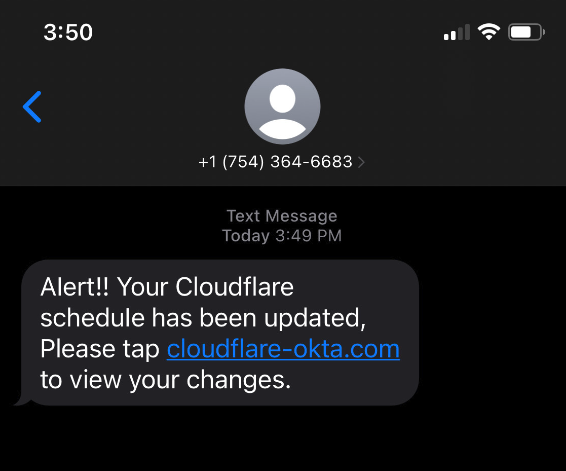

The phishers behind this scheme used newly-registered domains that often included the name of the target company, and sent text messages urging employees to click on links to these domains to view information about a pending change in their work schedule.

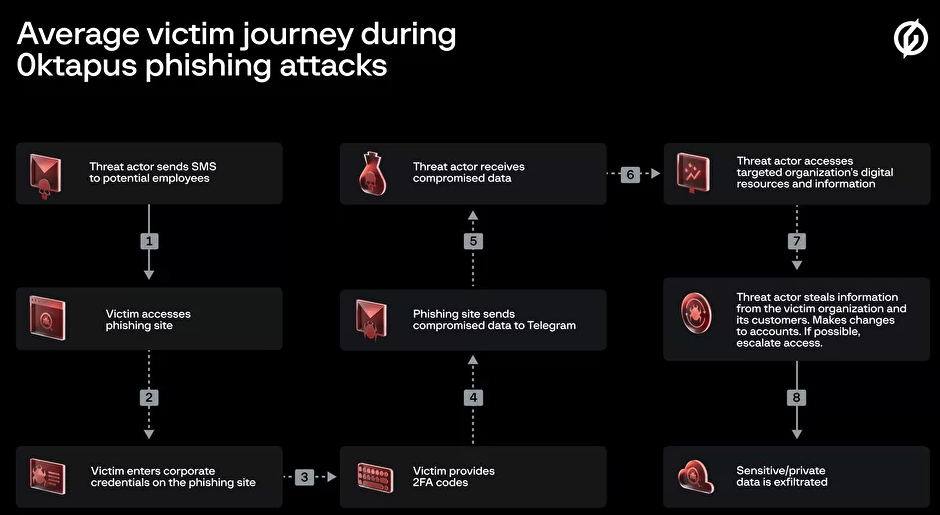

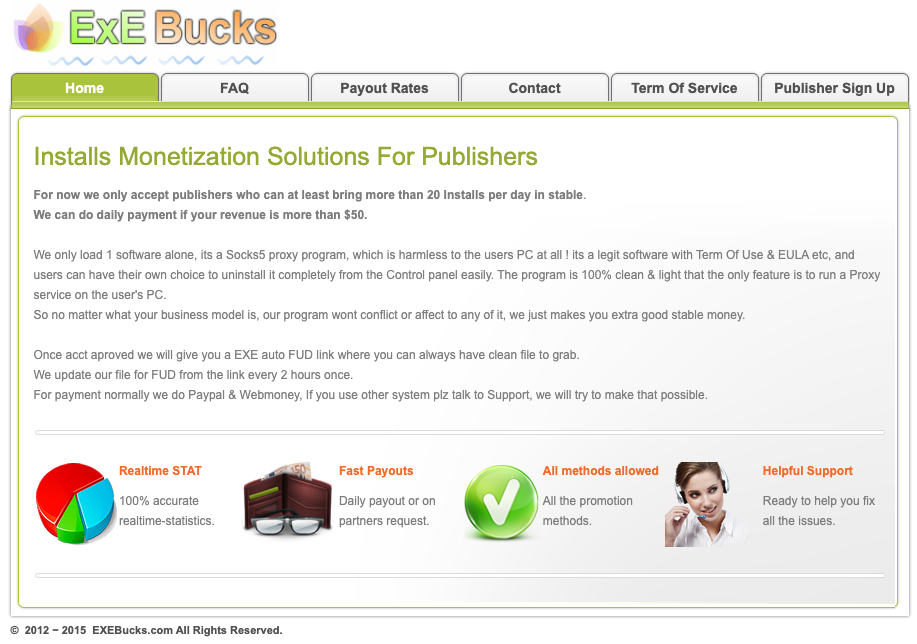

The phishing sites leveraged a Telegram instant message bot to forward any submitted credentials in real-time, allowing the attackers to use the phished username, password and one-time code to log in as that employee at the real employer website. But because of the way the bot was configured, it was possible for security researchers to capture the information being sent by victims to the public Telegram server.

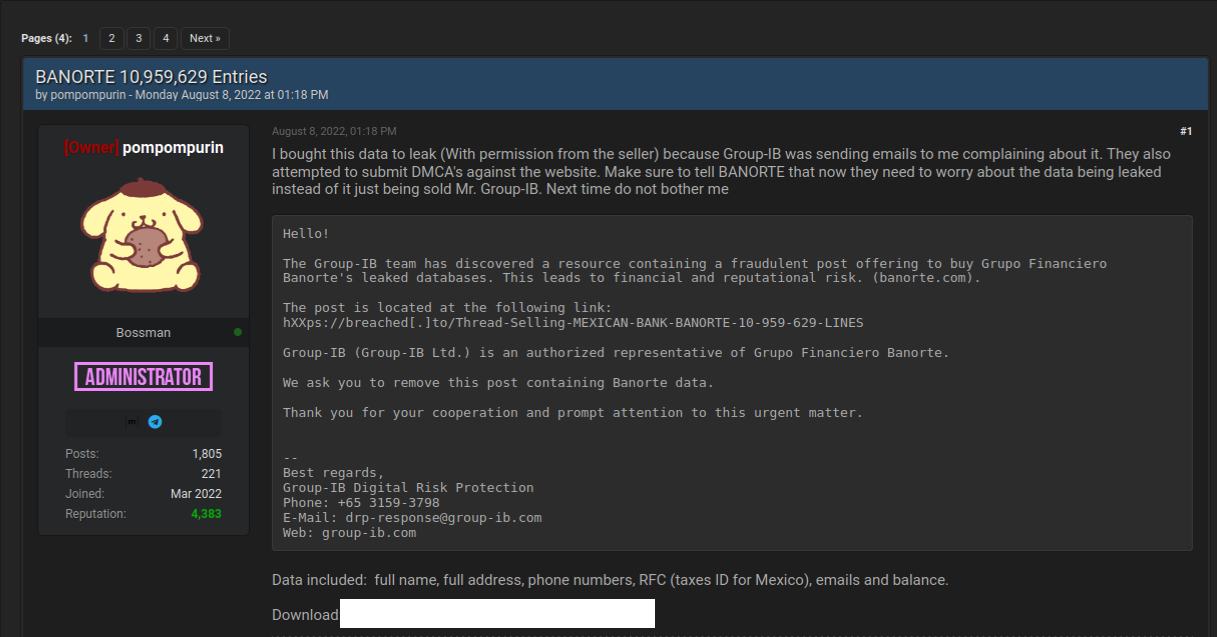

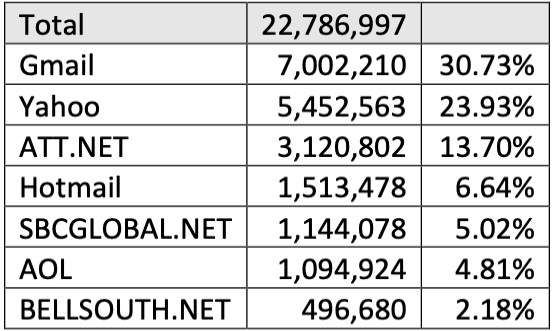

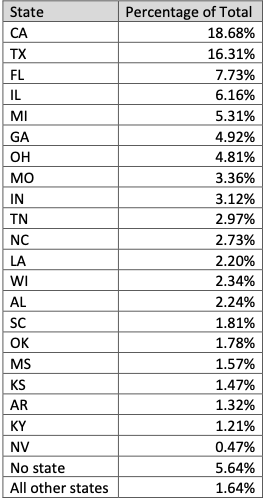

This data trove was first reported by security researchers at Singapore-based Group-IB, which dubbed the campaign “0ktapus” for the attackers targeting organizations using identity management tools from Okta.com.

“This case is of interest because despite using low-skill methods it was able to compromise a large number of well-known organizations,” Group-IB wrote. “Furthermore, once the attackers compromised an organization they were quickly able to pivot and launch subsequent supply chain attacks, indicating that the attack was planned carefully in advance.”

It’s not clear how many of these phishing text messages were sent out, but the Telegram bot data reviewed by KrebsOnSecurity shows they generated nearly 10,000 replies over approximately two months of sporadic SMS phishing attacks targeting more than a hundred companies.

A great many responses came from those who were apparently wise to the scheme, as evidenced by the hundreds of hostile replies that included profanity or insults aimed at the phishers: The very first reply recorded in the Telegram bot data came from one such employee, who responded with the username “havefuninjail.”

Still, thousands replied with what appear to be legitimate credentials — many of them including one-time codes needed for multi-factor authentication. On July 20, the attackers turned their sights on internet infrastructure giant Cloudflare.com, and the intercepted credentials show at least five employees fell for the scam (although only two employees also provided the crucial one-time MFA code).

Image: Cloudflare.com

In a blog post earlier this month, Cloudflare said it detected the account takeovers and that no Cloudflare systems were compromised. But Cloudflare said it wanted to call attention to the phishing attacks because they would probably work against most other companies.

“This was a sophisticated attack targeting employees and systems in such a way that we believe most organizations would be likely to be breached,” Cloudflare CEO Matthew Prince wrote. “On July 20, 2022, the Cloudflare Security team received reports of employees receiving legitimate-looking text messages pointing to what appeared to be a Cloudflare Okta login page. The messages began at 2022-07-20 22:50 UTC. Over the course of less than 1 minute, at least 76 employees received text messages on their personal and work phones. Some messages were also sent to the employees family members.”

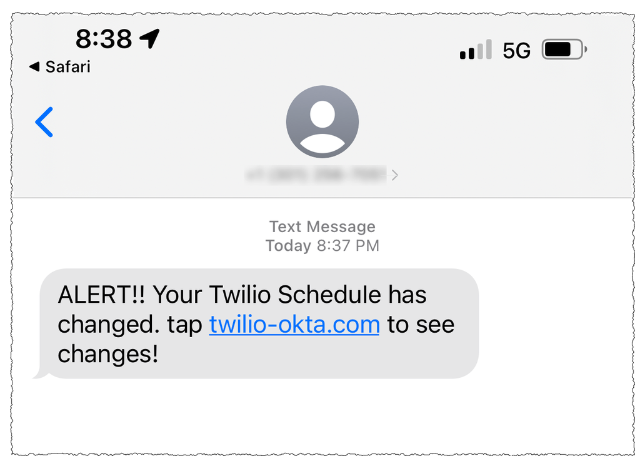

On three separate occasions, the phishers targeted employees at Twilio.com, a San Francisco based company that provides services for making and receiving text messages and phone calls. It’s unclear how many Twilio employees received the SMS phishes, but the data suggest at least four Twilio employees responded to a spate of SMS phishing attempts on July 27, Aug. 2, and Aug. 7.

On that last date, Twilio disclosed that on Aug. 4 it became aware of unauthorized access to information related to a limited number of Twilio customer accounts through a sophisticated social engineering attack designed to steal employee credentials.

“This broad based attack against our employee base succeeded in fooling some employees into providing their credentials,” Twilio said. “The attackers then used the stolen credentials to gain access to some of our internal systems, where they were able to access certain customer data.”

That “certain customer data” included information on roughly 1,900 users of the secure messaging app Signal, which relied on Twilio to provide phone number verification services. In its disclosure on the incident, Signal said that with their access to Twilio’s internal tools the attackers were able to re-register those users’ phone numbers to another device.

On Aug. 25, food delivery service DoorDash disclosed that a “sophisticated phishing attack” on a third-party vendor allowed attackers to gain access to some of DoorDash’s internal company tools. DoorDash said intruders stole information on a “small percentage” of users that have since been notified. TechCrunch reported last week that the incident was linked to the same phishing campaign that targeted Twilio.

This phishing gang apparently had great success targeting employees of all the major mobile wireless providers, but most especially T-Mobile. Between July 10 and July 16, dozens of T-Mobile employees fell for the phishing messages and provided their remote access credentials.

“Credential theft continues to be an ongoing issue in our industry as wireless providers are constantly battling bad actors that are focused on finding new ways to pursue illegal activities like this,” T-Mobile said in a statement. “Our tools and teams worked as designed to quickly identify and respond to this large-scale smishing attack earlier this year that targeted many companies. We continue to work to prevent these types of attacks and will continue to evolve and improve our approach.”

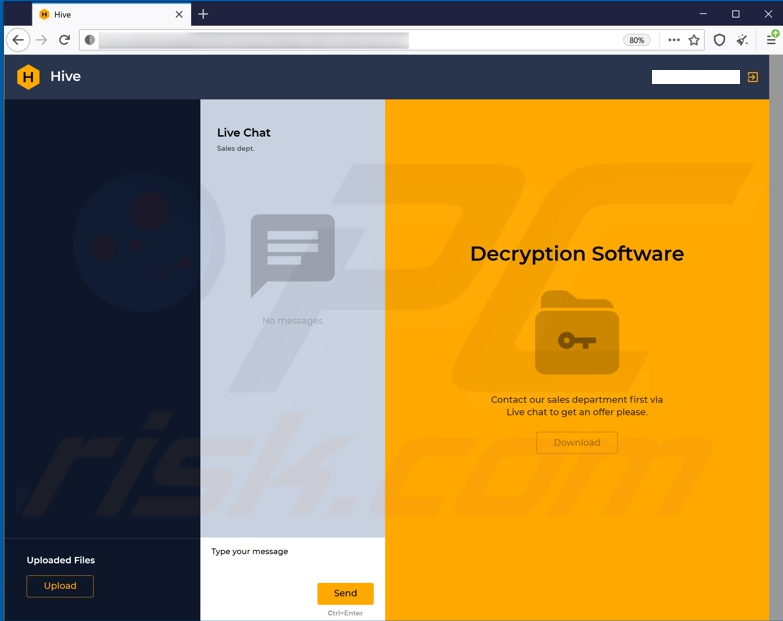

This same group saw hundreds of responses from employees at some of the largest customer support and staffing firms, including Teleperformanceusa.com, Sitel.com and Sykes.com. Teleperformance did not respond to requests for comment. KrebsOnSecurity did hear from Christopher Knauer, global chief security officer at Sitel Group, the customer support giant that recently acquired Sykes. Knauer said the attacks leveraged newly-registered domains and asked employees to approve upcoming changes to their work schedules.

Image: Group-IB.

Knauer said the attackers set up the phishing domains just minutes in advance of spamming links to those domains in phony SMS alerts to targeted employees. He said such tactics largely sidestep automated alerts generated by companies that monitor brand names for signs of new phishing domains being registered.

“They were using the domains as soon as they became available,” Knauer said. “The alerting services don’t often let you know until 24 hours after a domain has been registered.”

On July 28 and again on Aug. 7, several employees at email delivery firm Mailchimp provided their remote access credentials to this phishing group. According to an Aug. 12 blog post, the attackers used their access to Mailchimp employee accounts to steal data from 214 customers involved in cryptocurrency and finance.

On Aug. 15, the hosting company DigitalOcean published a blog post saying it had severed ties with MailChimp after its Mailchimp account was compromised. DigitalOcean said the MailChimp incident resulted in a “very small number” of DigitalOcean customers experiencing attempted compromises of their accounts through password resets.

According to interviews with multiple companies hit by the group, the attackers are mostly interested in stealing access to cryptocurrency, and to companies that manage communications with people interested in cryptocurrency investing. In an Aug. 3 blog post from email and SMS marketing firm Klaviyo.com, the company’s CEO recounted how the phishers gained access to the company’s internal tools, and used that to download information on 38 crypto-related accounts.

The ubiquity of mobile phones became a lifeline for many companies trying to manage their remote employees throughout the Coronavirus pandemic. But these same mobile devices are fast becoming a liability for organizations that use them for phishable forms of multi-factor authentication, such as one-time codes generated by a mobile app or delivered via SMS.

Because as we can see from the success of this phishing group, this type of data extraction is now being massively automated, and employee authentication compromises can quickly lead to security and privacy risks for the employer’s partners or for anyone in their supply chain.

Unfortunately, a great many companies still rely on SMS for employee multi-factor authentication. According to a report this year from Okta, 47 percent of workforce customers deploy SMS and voice factors for multi-factor authentication. That’s down from 53 percent that did so in 2018, Okta found.

Some companies (like Knauer’s Sitel) have taken to requiring that all remote access to internal networks be managed through work-issued laptops and/or mobile devices, which are loaded with custom profiles that can’t be accessed through other devices.

Others are moving away from SMS and one-time code apps and toward requiring employees to use physical FIDO multi-factor authentication devices such as security keys, which can neutralize phishing attacks because any stolen credentials can’t be used unless the phishers also have physical access to the user’s security key or mobile device.

This came in handy for Twitter, which announced last year that it was moving all of its employees to using security keys, and/or biometric authentication via their mobile device. The phishers’ Telegram bot reported that on June 16, 2022, five employees at Twitter gave away their work credentials. In response to questions from KrebsOnSecurity, Twitter confirmed several employees were relieved of their employee usernames and passwords, but that its security key requirement prevented the phishers from abusing that information.

Twitter accelerated its plans to improve employee authentication following the July 2020 security incident, wherein several employees were phished and relieved of credentials for Twitter’s internal tools. In that intrusion, the attackers used Twitter’s tools to hijack accounts for some of the world’s most recognizable public figures, executives and celebrities — forcing those accounts to tweet out links to bitcoin scams.

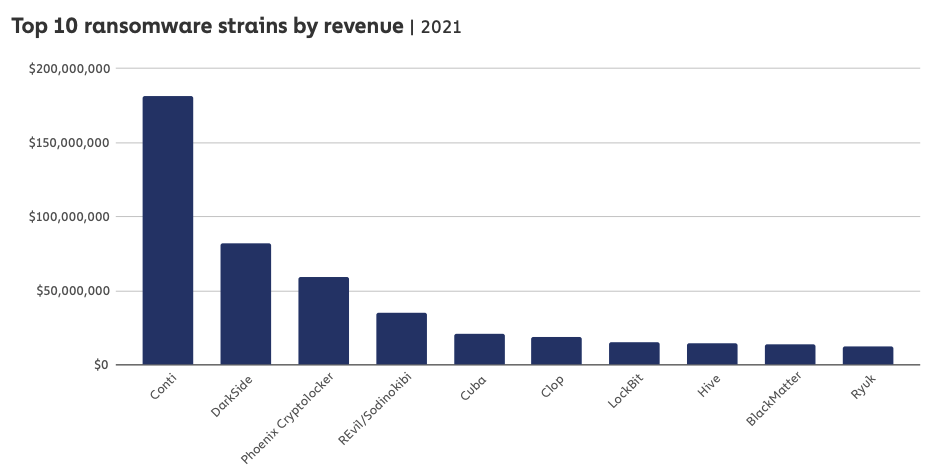

“Security keys can differentiate legitimate sites from malicious ones and block phishing attempts that SMS 2FA or one-time password (OTP) verification codes would not,” Twitter said in an Oct. 2021 post about the change. “To deploy security keys internally at Twitter, we migrated from a variety of phishable 2FA methods to using security keys as our only supported 2FA method on internal systems.”