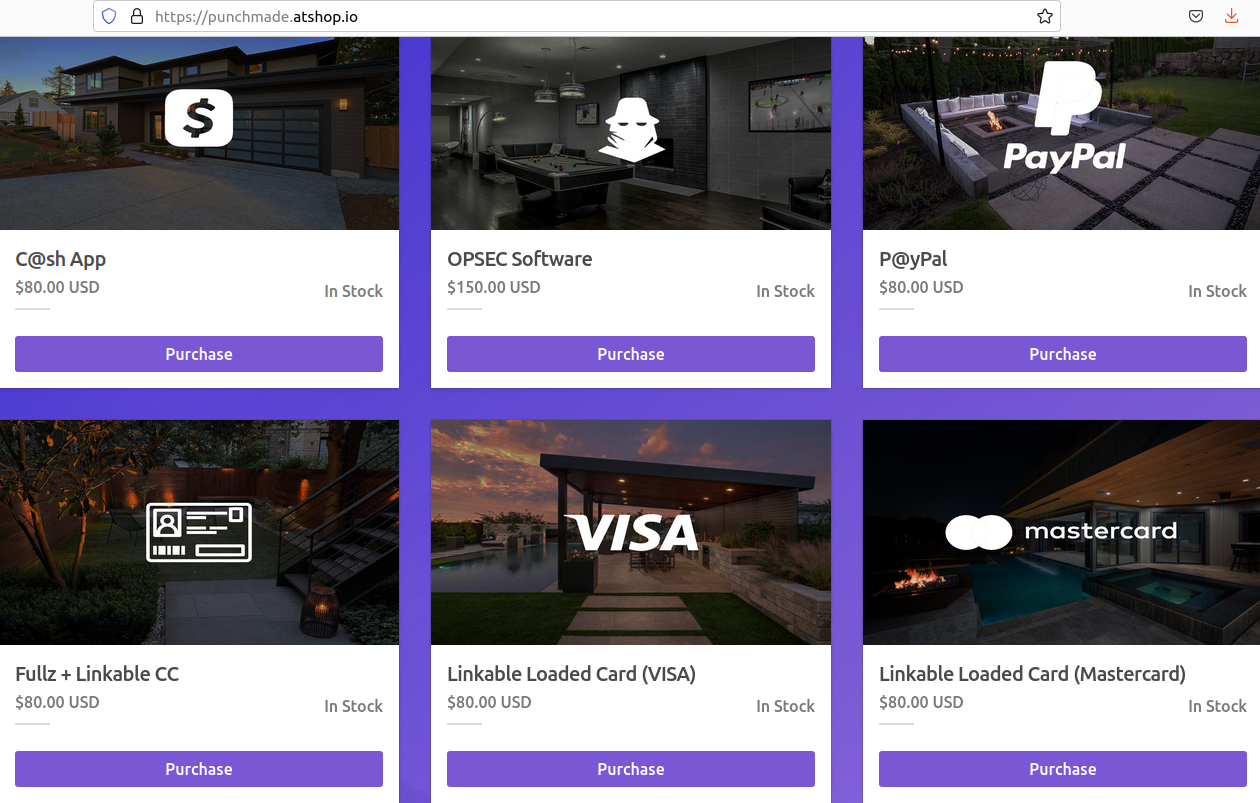

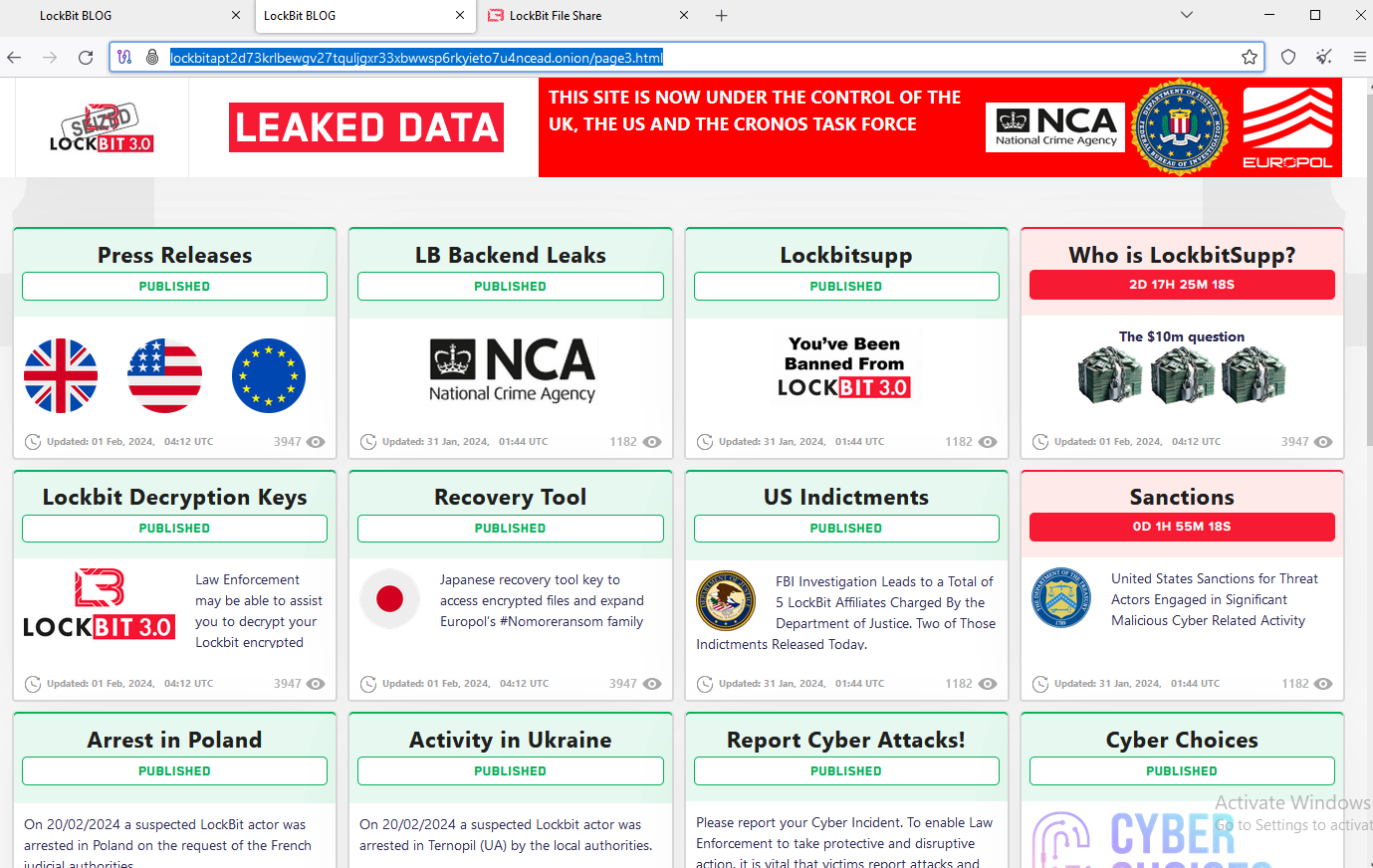

U.S. and U.K. authorities have seized the darknet websites run by LockBit, a prolific and destructive ransomware group that has claimed more than 2,000 victims worldwide and extorted over $120 million in payments. Instead of listing data stolen from ransomware victims who didn’t pay, LockBit’s victim shaming website now offers free recovery tools, as well as news about arrests and criminal charges involving LockBit affiliates.

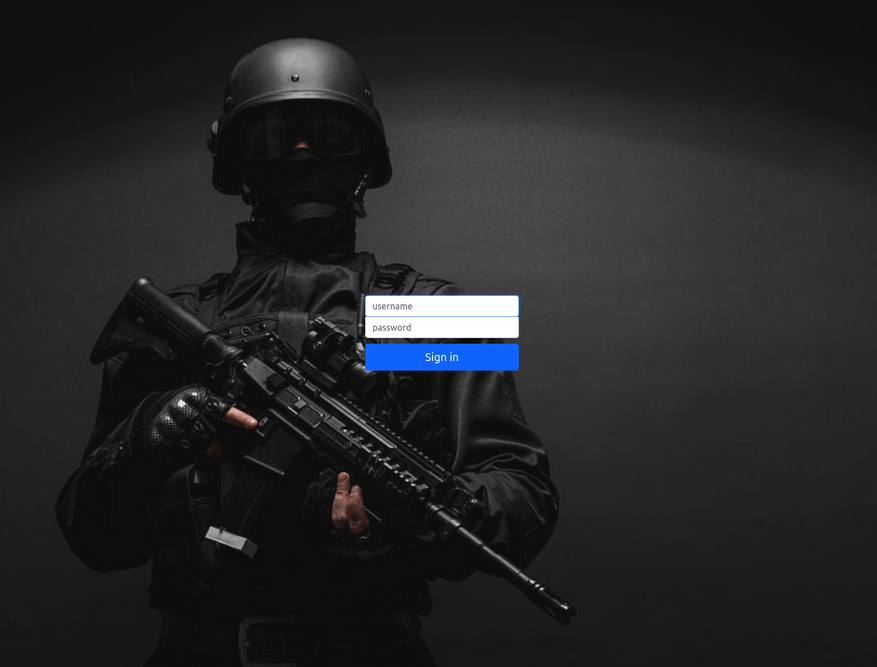

Investigators used the existing design on LockBit’s victim shaming website to feature press releases and free decryption tools.

Dubbed “Operation Cronos,” the law enforcement action involved the seizure of nearly three-dozen servers; the arrest of two alleged LockBit members; the unsealing of two indictments; the release of a free LockBit decryption tool; and the freezing of more than 200 cryptocurrency accounts thought to be tied to the gang’s activities.

LockBit members have executed attacks against thousands of victims in the United States and around the world, according to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ). First surfacing in September 2019, the gang is estimated to have made hundreds of millions of U.S. dollars in ransom demands, and extorted over $120 million in ransom payments.

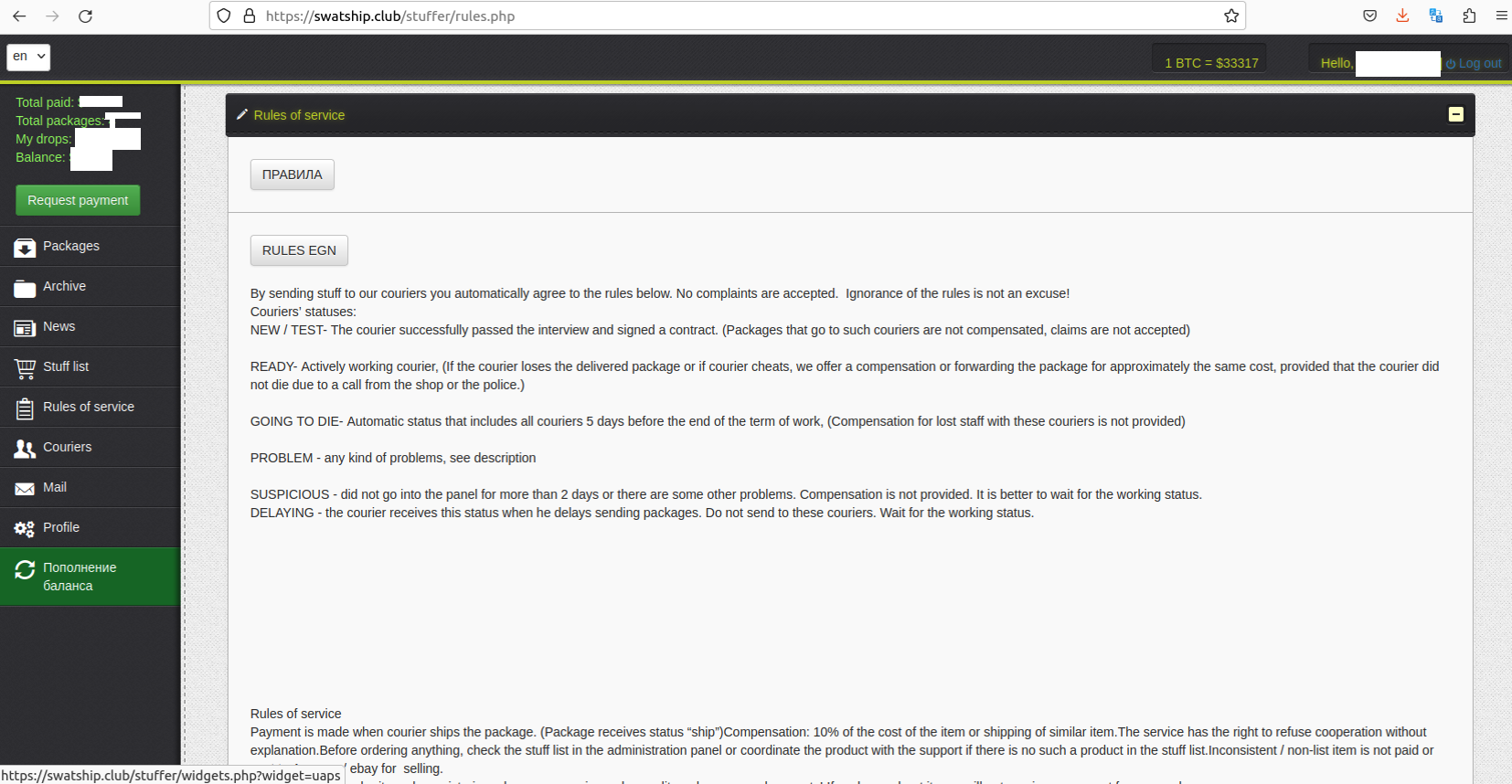

LockBit operated as a ransomware-as-a-service group, wherein the ransomware gang takes care of everything from the bulletproof hosting and domains to the development and maintenance of the malware. Meanwhile, affiliates are solely responsible for finding new victims, and can reap 60 to 80 percent of any ransom amount ultimately paid to the group.

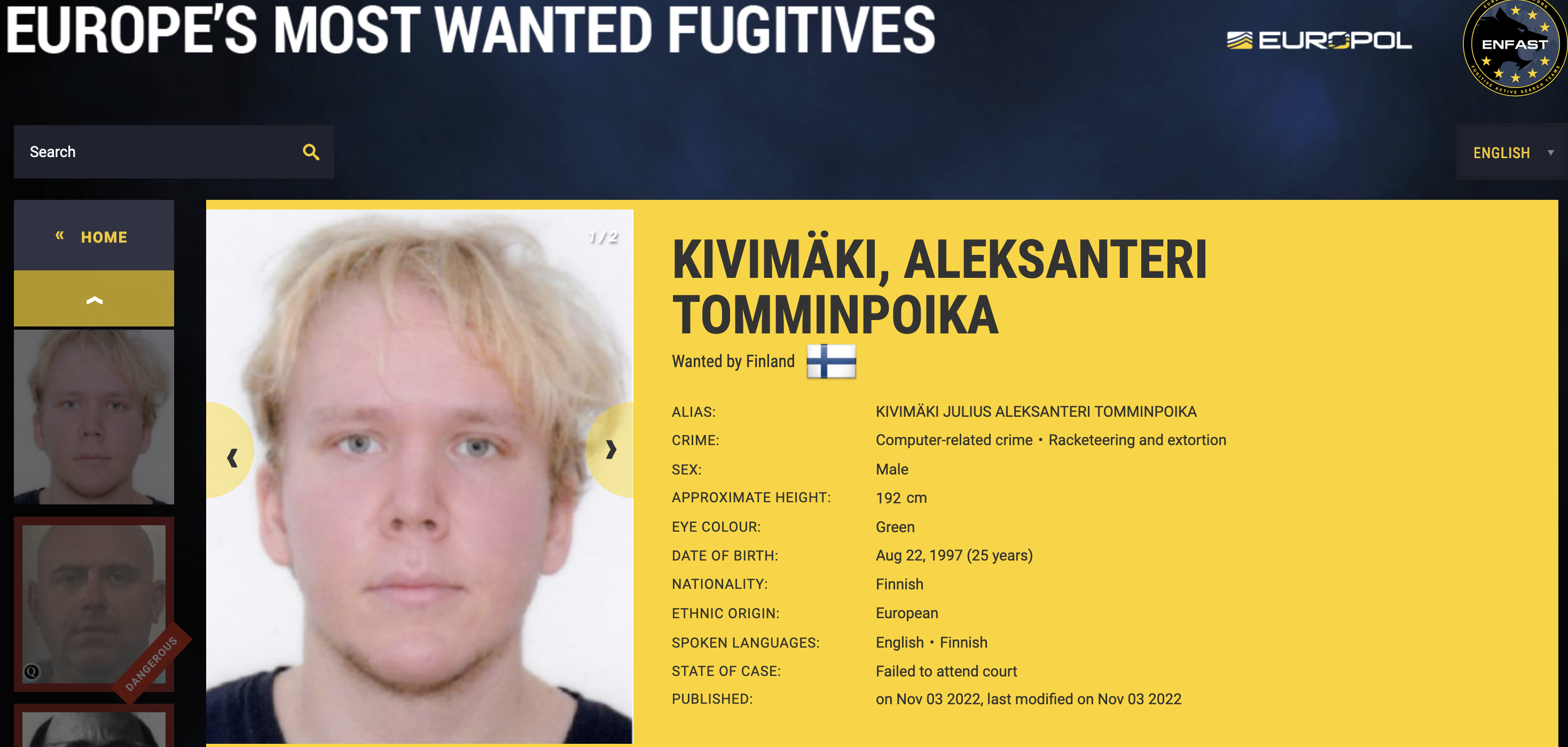

A statement on Operation Cronos from the European police agency Europol said the months-long infiltration resulted in the compromise of LockBit’s primary platform and other critical infrastructure, including the takedown of 34 servers in the Netherlands, Germany, Finland, France, Switzerland, Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom. Europol said two suspected LockBit actors were arrested in Poland and Ukraine, but no further information has been released about those detained.

The DOJ today unsealed indictments against two Russian men alleged to be active members of LockBit. The government says Russian national Artur Sungatov used LockBit ransomware against victims in manufacturing, logistics, insurance and other companies throughout the United States.

Ivan Gennadievich Kondratyev, a.k.a. “Bassterlord,” allegedly deployed LockBit against targets in the United States, Singapore, Taiwan, and Lebanon. Kondratyev is also charged (PDF) with three criminal counts arising from his alleged use of the Sodinokibi (aka “REvil“) ransomware variant to encrypt data, exfiltrate victim information, and extort a ransom payment from a corporate victim based in Alameda County, California.

With the indictments of Sungatov and Kondratyev, a total of five LockBit affiliates now have been officially charged. In May 2023, U.S. authorities unsealed indictments against two alleged LockBit affiliates, Mikhail “Wazawaka” Matveev and Mikhail Vasiliev.

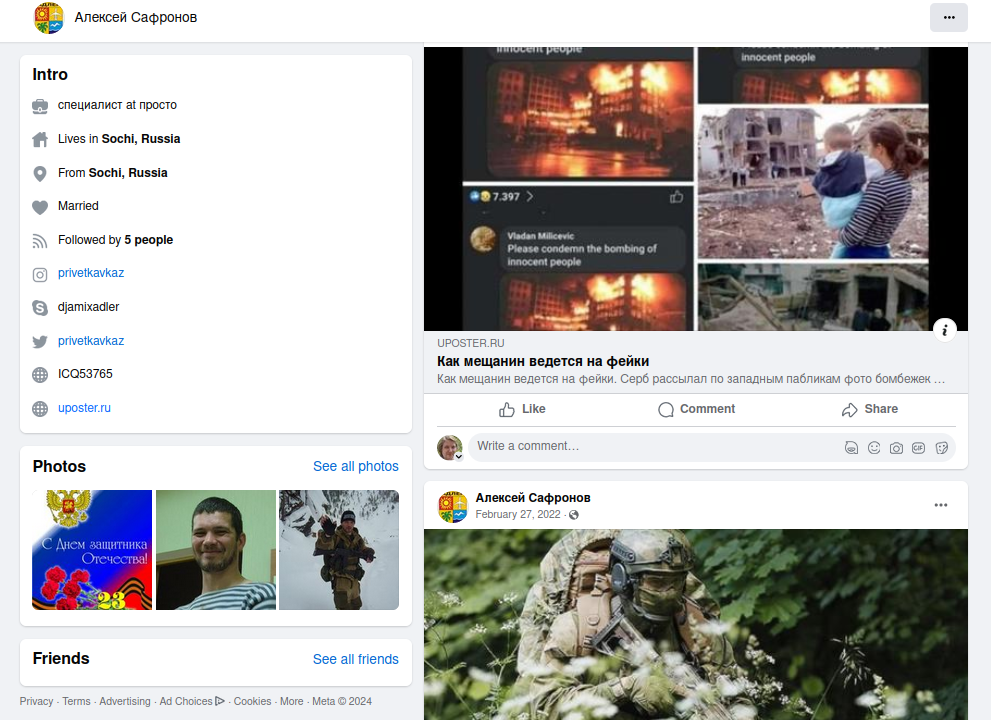

Vasiliev, 35, of Bradford, Ontario, Canada, is in custody in Canada awaiting extradition to the United States (the complaint against Vasiliev is at this PDF). Matveev remains at large, presumably still in Russia. In January 2022, KrebsOnSecurity published Who is the Network Access Broker ‘Wazawaka,’ which followed clues from Wazawaka’s many pseudonyms and contact details on the Russian-language cybercrime forums back to a 31-year-old Mikhail Matveev from Abaza, RU.

An FBI wanted poster for Matveev.

In June 2023, Russian national Ruslan Magomedovich Astamirov was charged in New Jersey for his participation in the LockBit conspiracy, including the deployment of LockBit against victims in Florida, Japan, France, and Kenya. Astamirov is currently in custody in the United States awaiting trial.

LockBit was known to have recruited affiliates that worked with multiple ransomware groups simultaneously, and it’s unclear what impact this takedown may have on competing ransomware affiliate operations. The security firm ProDaft said on Twitter/X that the infiltration of LockBit by investigators provided “in-depth visibility into each affiliate’s structures, including ties with other notorious groups such as FIN7, Wizard Spider, and EvilCorp.”

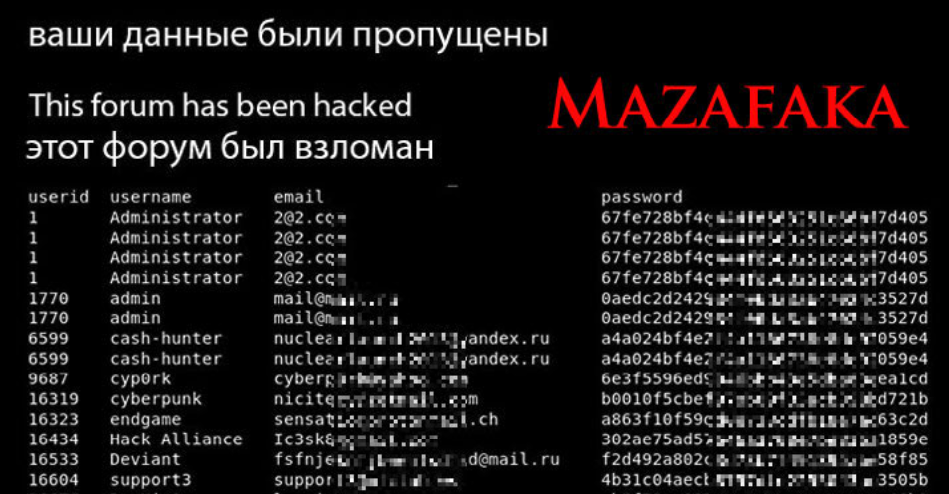

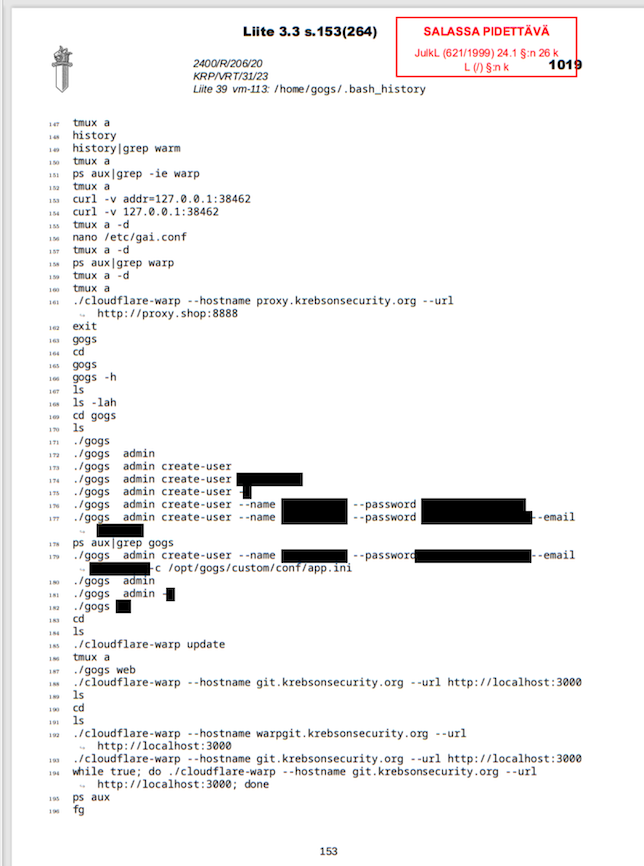

In a lengthy thread about the LockBit takedown on the Russian-language cybercrime forum XSS, one of the gang’s leaders said the FBI and the U.K.’s National Crime Agency (NCA) had infiltrated its servers using a known vulnerability in PHP, a scripting language that is widely used in Web development.

Several denizens of XSS wondered aloud why the PHP flaw was not flagged by LockBit’s vaunted “Bug Bounty” program, which promised a financial reward to affiliates who could find and quietly report any security vulnerabilities threatening to undermine LockBit’s online infrastructure.

This prompted several XSS members to start posting memes taunting the group about the security failure.

“Does it mean that the FBI provided a pentesting service to the affiliate program?,” one denizen quipped. “Or did they decide to take part in the bug bounty program? :):)”

Federal investigators also appear to be trolling LockBit members with their seizure notices. LockBit’s data leak site previously featured a countdown timer for each victim organization listed, indicating the time remaining for the victim to pay a ransom demand before their stolen files would be published online. Now, the top entry on the shaming site is a countdown timer until the public doxing of “LockBitSupp,” the unofficial spokesperson or figurehead for the LockBit gang.

“Who is LockbitSupp?” the teaser reads. “The $10m question.”

In January 2024, LockBitSupp told XSS forum members he was disappointed the FBI hadn’t offered a reward for his doxing and/or arrest, and that in response he was placing a bounty on his own head — offering $10 million to anyone who could discover his real name.

“My god, who needs me?,” LockBitSupp wrote on Jan. 22, 2024. “There is not even a reward out for me on the FBI website. By the way, I want to use this chance to increase the reward amount for a person who can tell me my full name from USD 1 million to USD 10 million. The person who will find out my name, tell it to me and explain how they were able to find it out will get USD 10 million. Please take note that when looking for criminals, the FBI uses unclear wording offering a reward of UP TO USD 10 million; this means that the FBI can pay you USD 100, because technically, it’s an amount UP TO 10 million. On the other hand, I am willing to pay USD 10 million, no more and no less.”

Mark Stockley, cybersecurity evangelist at the security firm Malwarebytes, said the NCA is obviously trolling the LockBit group and LockBitSupp.

“I don’t think this is an accident—this is how ransomware groups talk to each other,” Stockley said. “This is law enforcement taking the time to enjoy its moment, and humiliate LockBit in its own vernacular, presumably so it loses face.”

In a press conference today, the FBI said Operation Cronos included investigative assistance from the Gendarmerie-C3N in France; the State Criminal Police Office L-K-A and Federal Criminal Police Office in Germany; Fedpol and Zurich Cantonal Police in Switzerland; the National Police Agency in Japan; the Australian Federal Police; the Swedish Police Authority; the National Bureau of Investigation in Finland; the Royal Canadian Mounted Police; and the National Police in the Netherlands.

The Justice Department said victims targeted by LockBit should contact the FBI at https://lockbitvictims.ic3.gov/ to determine whether affected systems can be successfully decrypted. In addition, the Japanese Police, supported by Europol, have released a recovery tool designed to recover files encrypted by the LockBit 3.0 Black Ransomware.