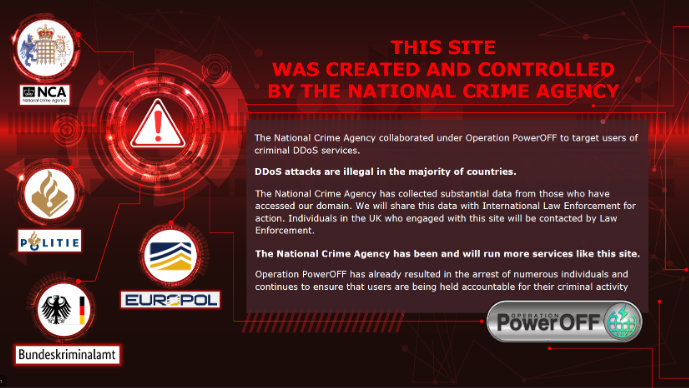

The U.S. government today announced a coordinated crackdown against QakBot, a complex malware family used by multiple cybercrime groups to lay the groundwork for ransomware infections. The international law enforcement operation involved seizing control over the botnet’s online infrastructure, and quietly removing the Qakbot malware from tens of thousands of infected Microsoft Windows computer systems.

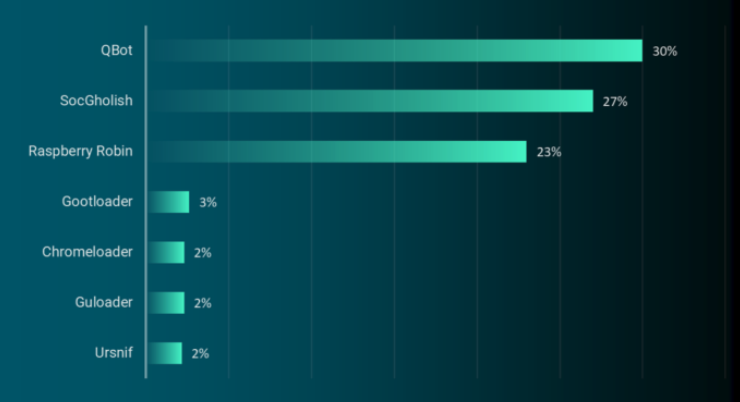

Qakbot/Qbot was once again top malware loader observed in the wild in the first six months of 2023. Source: Reliaquest.com.

In an international operation announced today dubbed “Duck Hunt,” the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) said they obtained court orders to remove Qakbot from infected devices, and to seize servers used to control the botnet.

“This is the most significant technological and financial operation ever led by the Department of Justice against a botnet,” said Martin Estrada, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of California, at a press conference this morning in Los Angeles.

Estrada said Qakbot has been implicated in 40 different ransomware attacks over the past 18 months, intrusions that collectively cost victims more than $58 million in losses.

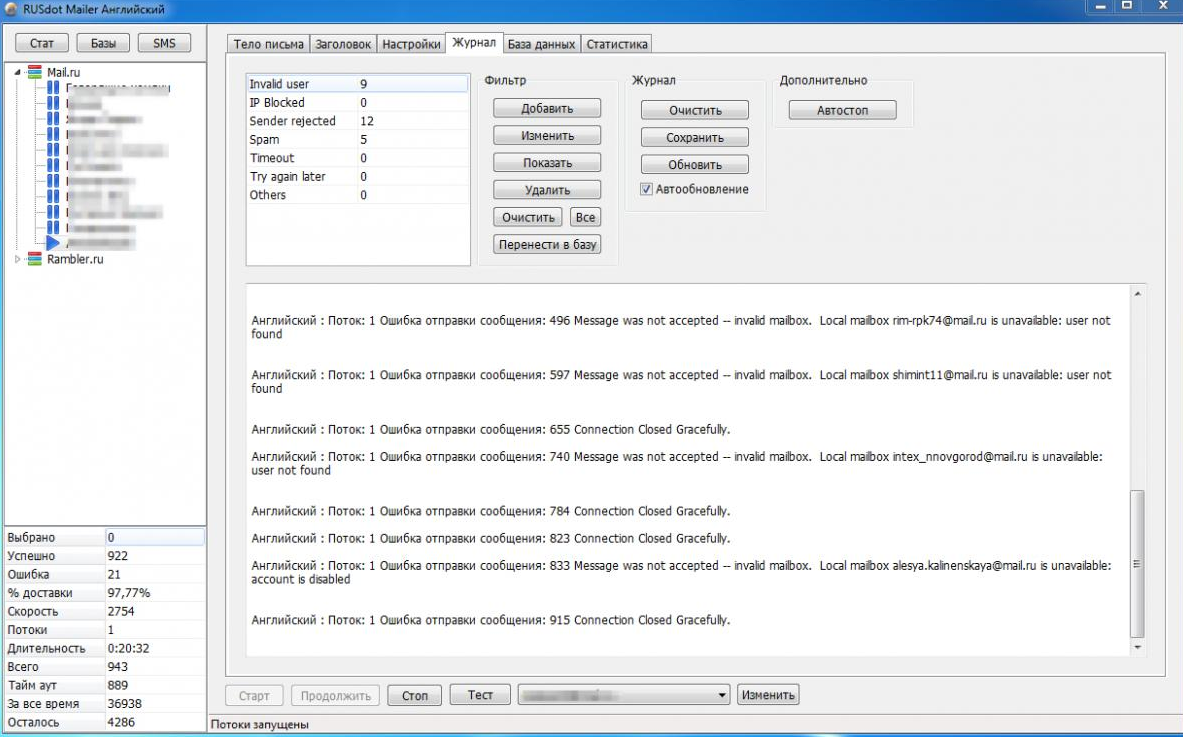

Emerging in 2007 as a banking trojan, QakBot (a.k.a. Qbot and Pinksplipbot) has morphed into an advanced malware strain now used by multiple cybercriminal groups to prepare newly compromised networks for ransomware infestations. QakBot is most commonly delivered via email phishing lures disguised as something legitimate and time-sensitive, such as invoices or work orders.

Don Alway, assistant director in charge of the FBI’s Los Angeles field office, said federal investigators gained access to an online panel that allowed cybercrooks to monitor and control the actions of the botnet. From there, investigators obtained court-ordered approval to instruct all infected systems to uninstall Qakbot and to disconnect infected machines from the botnet, Alway said.

The DOJ says their access to the botnet’s control panel revealed that Qakbot had been used to infect more than 700,000 machines in the past year alone, including 200,000 systems in the United States.

Working with law enforcement partners in France, Germany, Latvia, the Netherlands, Romania and the United Kingdom, the DOJ said it was able to seize more than 50 Internet servers tied to the malware network, and nearly $9 million in ill-gotten cryptocurrency from QakBot’s cybercriminal overlords. The DOJ declined to say whether any suspects were questioned or arrested in connection with Qakbot, citing an ongoing investigation.

According to recent figures from the managed security firm Reliaquest, QakBot is by far the most prevalent malware “loader” — malicious software used to secure access to a hacked network and help drop additional malware payloads. Reliaquest says QakBot infections accounted for nearly one-third of all loaders observed in the wild during the first six months of this year.

Researchers at AT&T Alien Labs say the crooks responsible for maintaining the QakBot botnet have rented their creation to various cybercrime groups over the years. More recently, however, QakBot has been closely associated with ransomware attacks from Black Basta, a prolific Russian-language criminal group that was thought to have spun off from the Conti ransomware gang in early 2022.

Today’s operation is not the first time the U.S. government has used court orders to remotely disinfect systems compromised with malware. In April 2022, the DOJ quietly removed malware from computers around the world infected by the “Snake” malware, an even older malware family that has been tied to the GRU, an intelligence arm of the Russian military.

Documents published by the DOJ in support of today’s takedown state that beginning on Aug. 25, 2023, law enforcement gained access to the Qakbot botnet, redirected botnet traffic to and through servers controlled by law enforcement, and instructed Qakbot-infected computers to download a Qakbot Uninstall file that uninstalled Qakbot malware from the infected computer.

“The Qakbot Uninstall file did not remediate other malware that was already installed on infected computers,” the government explained. “Instead, it was designed to prevent additional Qakbot malware from being installed on the infected computer by untethering the victim computer from the Qakbot botnet.”

The DOJ said it also recovered more than 6.5 million stolen passwords and other credentials, and that is has shared this information with two websites that let users check to see if their credentials were exposed: Have I Been Pwned, and a “Check Your Hack” website erected by the Dutch National Police.

Further reading:

–The DOJ’s application for a search warrant application tied to Qakbot uninstall file

–The search warrant application connected to QakBot server infrastructure in the United States

–The government’s application for a warrant to seize virtual currency from the QakBot operators.